Based on primary sources and archival records of the slave trade

Written for Rebecca Scott’s history seminar: The Law in Slavery and Freedom

Read / download essay as PDF, opens in new tab

Selling slaves equipped Liverpool merchant Thomas Leyland with the money to create what is now the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank of China. With profits from merchant trading and Caribbean slave sales, Leyland wrote thousands of letters to build a Transatlantic business. Analyzing these 250-year-old business records reveals the mechanisms of human trafficking.

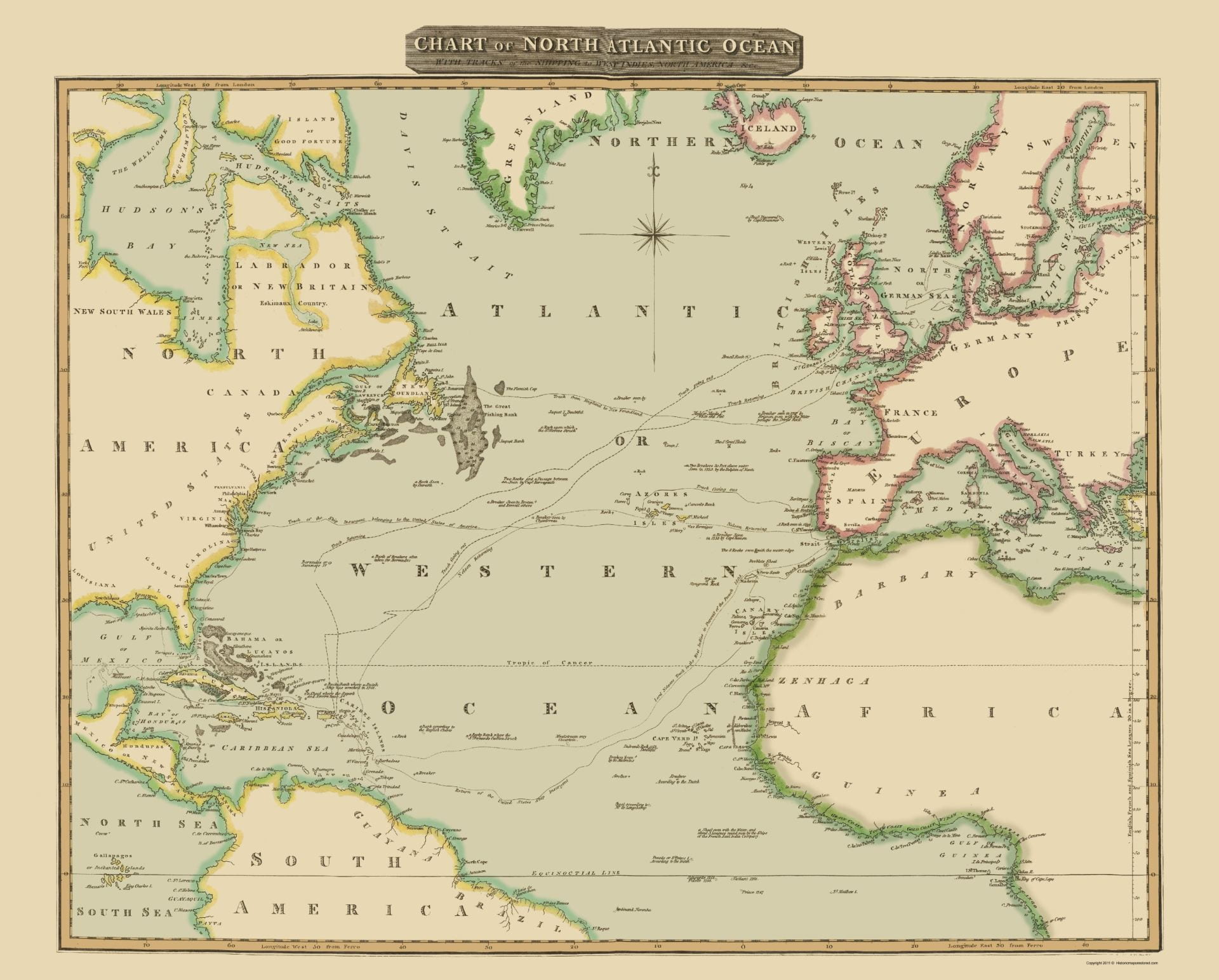

From the comfortable distance of Liverpool, Bristol, and London, Leyland’s letters describe bodies he and his co-investors would never see some 4,500 miles away in the Caribbean. In an age before telegraphs, steamships, and rapid transcontinental communication, Leyland required a paper trail to carry out his orders. Across the distant branches of his global business empire, the medium of written letters linked these distant investments to London.

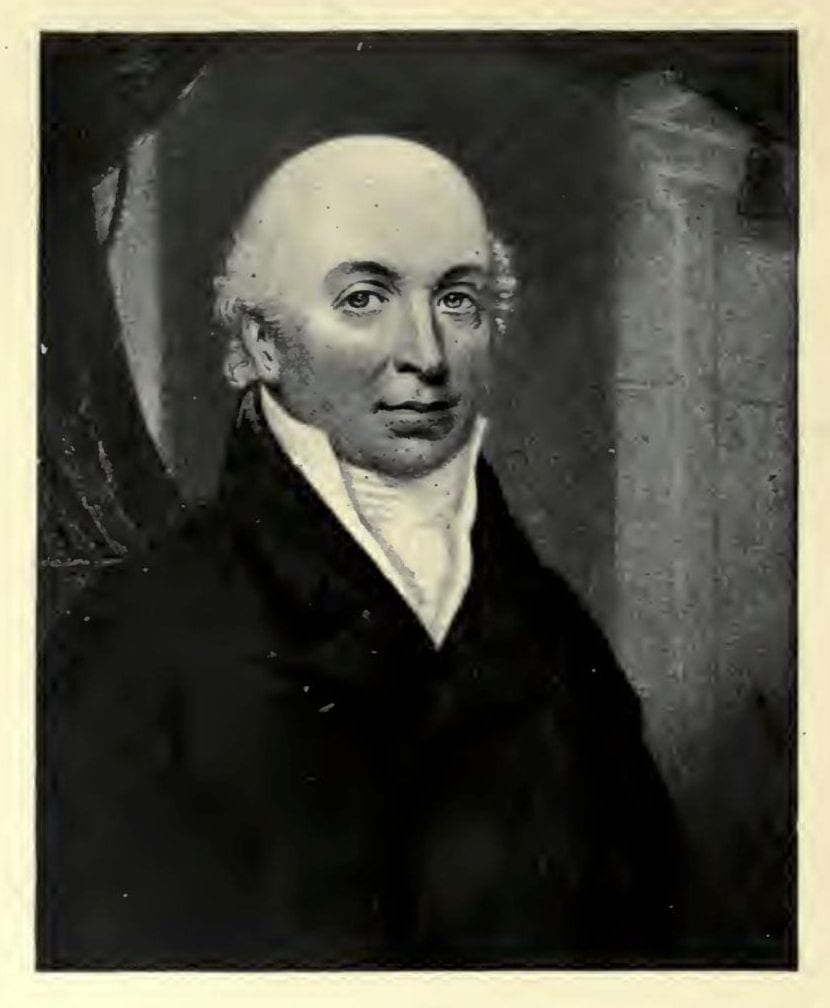

Thomas Leyland was a banker, trader, millionaire, and three times Mayor of Liverpool. Born 1752 to working class family of limited means, little land, and no royal titles, he chanced upon wealth when in 1776 he won £20,000 in the lottery. He was only twenty-four. This wealth he first invested in merchant ships to sell consumer goods and transport the likes of oats, peas, wheat, oatmeal, bacon, hogs, and lard from Irish farmers to British markets.[1] By 1783, with profits from these businesses, Leyland turned to the risk-intensive capital required to launch slave voyages, purchasing captives on the West African coast and selling them to cotton and sugar plantations in the Caribbean. His ~70 recorded slaving voyages transported an estimated 22,365 captives to the Americas, of whom about one in ten died during the months-long voyage. By his death in 1827, Leyland had amassed a fortune of some £600,000.[2]

Examination of his account books in Liverpool and at the University of Michigan show the 1789-90 journey of the Hannah with 294 African captives and the 1792-92 journey of the Jenny with 250 captives. Both year-long journeys began in Liverpool, sailed for West Africa, exchanged guns and cloth for human cargo, sold their captives in Jamaica, and then sailed home to Britain. His written correspondence of 2,262 letters also survives in the Liverpool Record Offices. Close reading of these documents in parallel – the ship manifest and the letter book – unpacks the mechanics and finances of Leyland’s slaving operation turned modern bank.

These documents reveal the mechanisms and mentality of a human trafficker. Never in them does Leyland claim – as a moral cover for their profit motives – that such African bodies were being saved from a darker fate of certain death from their African captors. These letters never claimed either that slavery was justified. Nor did Leyland use the cover of Christianity and the Christian language of missionary work to justify in his letters what he did to these Africans. His few written comments on the subject do not even recognize the need to justify slavery, the slave trade, or his role in it.[3]

Instead, the letters present the trafficking of human cargo in matter-of-fact language. In one day’s correspondence and from the same desk, Leyland ordered his agents to landscape the lawn of his country house, purchase grain from Ireland, deliver rum to an associate, and sell Africans in Jamaica. The tone of Leyland’s writing in flowing cursive script and flowery prose does not change, whether discussing matters as banal as drapery or as life changing as human trafficking. From Liverpool, Leyland managed business but at no point had he ever seen or inspected the human products he was buying, and nor did his London colleagues. In this way, these letters all describe slaves in the abstract, as bodies, as cargo, and profits per head sold. Leyland’s writing transforms the human body – a name, a person, a fate – into nothing more than a number on a page.

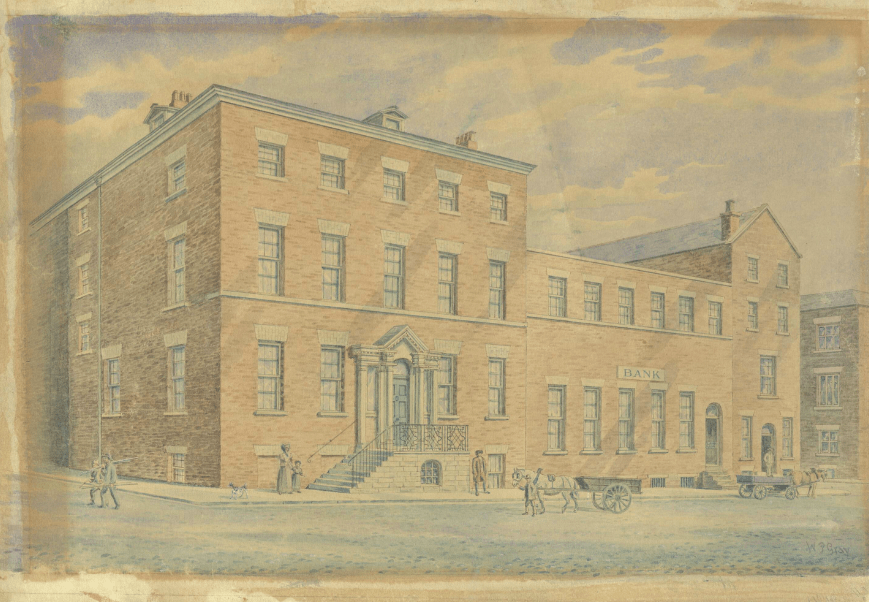

Watercolor of Leyland & Bullins bank on York Street in Liverpool in 1807. Bank offices at right. Leyland’s family home at left. Warehouse for Caribbean rum, Irish oats, and slave trade goods in rear. This building survives today unchanged. [4].

Read More

.

1. Preparing a Slave Ship: Manchester’s Industrial Revolution made Leyland’s slave trade possible.

From the comfort of his home office on York Street in Liverpool, shown above, Thomas Leyland secured potential buyers: He sent letters to colleagues in Liverpool and London. His colleagues each worked or owned outright sugar and cotton plantations in the Caribbean. Leyland informed each colleague when his ship of African captives was arriving in the Caribbean, and then asked if they were interested to buy from this ship. For instance, as Leyland wrote in August 1788 to James Baillie of London: “We shall be much obliged to you for your guarantee for your friends at Grenada, Dominica, & St. Vincent for the sale of the ship Christopher’s cargo. Captain Maxwell, who we expect to arrive in Barbados in December next with 250 to 270 Angola Negroes.”[5]

With letters of guarantee and promises from purchasers, Leyland then organized a slave ship. He contacted British manufacturers of clothes, fabric, silk, and other products. He transported them by land and then brought them aboard the Hannah to exchange for slaves. In March 1788, for instance, Leyland instructed Hannah Captain Charles Wilson to buy silk and cotton from Mr. Rawhuson in Manchester:

I request you will now order from Mather & Co 200 silk & cotton romalls, red, white blue, and with as little yellow in as possible, provided the price does not exceed about 14, the price heretofore paid by Caton [West African agent], who has explained to me how much preferable you will find this article in your trade.[6]

After loading 27 barrels of rum, fabric, and hundreds of other goods on the Hannah, Leyland drafted a detailed letter to Captain Wilson in June 1789. His letter inventoried the ship’s contents and suggested to Captain Wilson the ideal price to purchase and sell African captives. Leyland also shared in this letter to Wilson the names and addresses of Caribbean owners who had agreed to purchase Africans.

“Sales of 250 slaves imported in the ship Jenny, Captain William Stringer, from Angola on account of Thomas Leyland & Co, merchants in Liverpool” [7] Investor Thomas Leyland received two thirds of the profits. His cousin by marriage, Thomas Molyneux, received one third. Rather than listing captives by name, the center six columns list the number of slaves in each of six age groups: men, men-boys, boys, women, women-girls, and girls. Young girls without children or previous sexual relationships sold for a premium on slave markets. They were usually then raped by their new master, to produce mix-raced children who in turn were resold years later. In this way, girls’ bodies were investment vehicles to – literally – give birth to and extract future profits.

2. Managing a Slave Ship: The death of African captives was not an exception or flaw in Leyland’s financial system. Death was intentional and calculated to maximize profit.

What was the form and body of the ideal African captive to Leyland? Obedient. Docile. Young. Intelligent. But not too intelligent they could question authority.

The answers are found in ship manifests from the trade, instructions from English merchants to ship captains, and from plantation owners to their purchasers. They describe the bodies of captured peoples, their desired attributes, their height, gender, age, and physical form. For instance, Leyland wrote to Captain Wilson of the Hannah in 1789:

“It is most certain the healthy, young, and beautiful Negroes of that Country stand the only chance of being carried to a market in good condition.” In addition, consider “humanity and utmost tenderness to the Negroes, as particularly conducive to the prosperity of the voyage.” [8]

“Tenderness” and “humanity” did not code for the best interests and desires of the captives. Instead, these words code for Leyland’s desire that the captives were treated just well enough to survive and make it market on the 37-day transatlantic journey. In fact, Leyland budgeted to buy more slaves than he knew he would sell. He generally bought between five and ten percent more slaves per journey than he needed, in full knowledge that many would never make it across the ocean. When they died at sea, their bodies – on the orders of Captain Wilson – were tossed to the ocean. However, the Jenny and Hannah manifests neglected to mention deaths. In some cases, slave deaths were thought so unimportant and irrelevant that the names and ages of those who died were never recorded in writing.[9]

On arrival, Leyland negotiated prices with the auction houses of Michell & Daggers for the Hannah’s voyage, and Lindo & Lake for the Jenny’s voyage. Leyland had a rough idea of future profits. But when slaves arrived in Caribbean markets sick, tired, and near death, resale prices were lower. Leyland’s ships usually sold first in Barbados, St. Vincent, and the easternmost Caribbean islands. These were the Caribbean islands closest to West Africa. If no buyers were found in these markets, ships sailed 1,200 miles further west to Jamaica. The onward sail to Jamaica was always a risk because the longer Leyland held his captives, the more would die each day. As Leyland wrote to Captain Wilson: “Rather than accept of a low average [in Barbados] for a choice cargo, by all means proceed to Jamaica.[10] The longer he held his human merchandise of “choice cargo,” the lower its value. “Choice cargo” – be they human, fruit, or wheat to Leyland – all required fast turnaround and resale to maximize profit before they all spoiled.

Leyland timed his voyages and adjusted the ship’s contents in response to his predictions of market demand. Cotton prices and slave prices fluctuated seasonally. For some voyages, it was more profitable to exchange slaves for Caribbean cotton and rum, particularly if cotton was selling for high prices in British markets. For other voyages, promissory notes were preferable. For instance, as Leyland wrote to Captain Wilson on December 9, 1786: “We wish you to fill the ship with cotton of good quality if it can be got cheap, the present high prices cannot continue and we beg you will not agree to take any other produce on any consideration, so much money is likely to be lost by it.” [11]

The trade was immensely profitable. For instance, in the 1792-93 voyage of the Jenny, Leyland bought 5,940 yards of colorful printed cotton fabric from Manchester worth £234, or about £1 per 25 yards of fabric. When bartering fabric for slaves, the initial exchange price was suggested as just 25 yards of fabric, or the equivalent value of just £1. That is, goods were purchased on the cheap in European markets and exchanged for profit in African markets.

By contrast, while Leyland suggested buying a slave for the equivalent of just £1, suggested resale values began at £46 in Caribbean markets. That is, slaves were sold for up to 46 times more than they were purchased. This voyage alone, based on purchasing slaves for £234 worth of fabric, yielded a gross income £13,500 from the sale of these same slaves. Of this £13,500, most went to labor costs, materials, and paying the captain and crew. The remaining ~£4,000 was Leyland’s profit

.

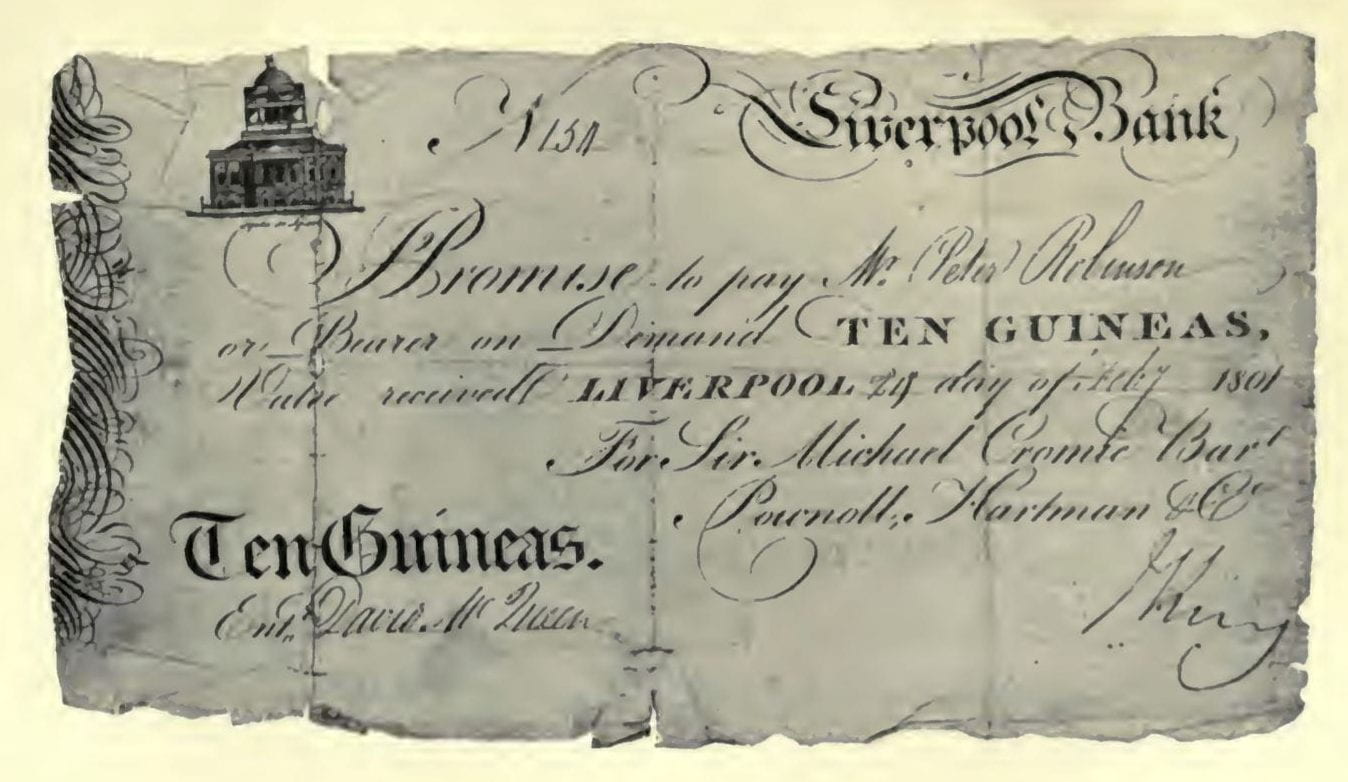

Associate of Thomas Leyland Sir Michael Cromie & Co.’s Ten-Guinea Promissory Note: “Promise to pay to Mr. Peter Robinsen [sic.] or bearer on demand TEN GUINEAS, after received LIVERPOOL 29 day of July 1801” [12]

3. Slave Financing: Selling slaves motivated Leyland to experiment with innovative new financial products and modern forms of finance.

At sale, slaves could be exchanged for rum, cotton, sugar, cash – or as Leyland increasingly used – promissory notes. A single slave might be exchanged one ton or more of cotton. A full slave ship might be exchanged for more cotton than could possibly fit on the return ship home. Therefore, exchange of slaves for more liquid cash and hard currency was preferable. Some Caribbean buyers had the money to do this; others did not.

Leyland therefore secured letters of promise. The ship manifest recorded the names of who bought slaves, the quantity purchased, and the price paid for each. Those without cash on hand, signed a promissory note with the number and value of slaves they purchased. The promissory notes, like the one showed above, was basically a check. But unlike a modern check, Leyland did not present the promissory note at his own bank. He instead presented the check at the London or Liverpool bank of the person from whom he purchased the slaves. This bank would verify if the check was valid and draw from their customer’s funds to give to Leyland. Leyland had to trust these letters were good, and that British corporations like Baillie & Co. would make good on their promise to refund. Trust was key. For instance, as Leyland wrote to Charles Wilson on August 31, 1788: “If you should be obliged to go to Jamaica you may apply to Messrs. Hibbert & Co as well as to Mr. Lindo, because their house in London will accept their bills.”[13]

Shortage of specie currency in the Caribbean and dangers of transporting money over long distances motivated Leyland to rely on handshake agreements, promissory notes, and checks in lieu of hard currency. However, there must have been many cases of buyers with bad credit histories. As Leyland warned Captain Wilson in December 1786: “Be very particularly in your agreements with the house who sells your cargo, of by that means all disputes or any disappointment may be avoided.”[14] Leyland must have learned the dangers of promissory notes from hard experience. For instance, in August 1788, he wrote to Joseph Barton who had taken goods from Leyland without payment: “I now enclose Captain Swainston’s protest, which I hope will enable you to settle the average on the ship. [….] Favor me with these accounts as soon as possible.”[15] Later in September 1788, with still no payments made, Leyland again scolded Barton: “I much fear after payment of the bond debts.”[16]

Promissory notes were also loans. For instance, a buyer could draw up a letter promising to pay, even if there was not enough money in his bank account at that time to make good the payment. Before entering banking, Leyland experimented with using slaves as collateral on loans. In short, the planter agreed to repay him in increments of 6, 12, or 18 months later, based on future profits.[17]

This practice allowed buyers to speculate on slaves, to buy slaves with money they did not have, and to pay off the slave debt with future profits from slave labor. In other words, slaves became collateral on loans and could be taken back by creditors over unpaid debt.

Captain Wilson had a lot of responsibility: to buy slaves, transport them, draw up legally binding sale documents, and help Leyland collect loan payment from British banks. In an age before credit scores and modern banks, Leyland’s financial system relied on building long-term business relationships, handshake agreements, gossip, and word of mouth. Most of all, Leyland’s system relied on trust. If a slave buyer did not have enough money, could Leyland trust to loan him money?

The size of an ocean allowed Leyland to comfortably collect profits from captives he never saw or met. Leyland’s letters distanced him from site of his crimes. Slavery and death became abstract to Leyland, reduced to mere numbers and tick marks on a page. But this same ocean made communication and reimbursement difficult. London merchants had to commit to buying slaves in Caribbean markets they never saw. Liverpool slavers had to hand the day-to-day responsibility of managing a ship to captains like Charles Wilson, who could disappear while at sea during months without contact. Caribbean buyers had to buy slaves and draw up promissory notes, hoping there was enough money in London markets to cash the notes.

|

|

|

4. Leyland Turned Benefactor and Banker: Leyland used profits and skills learned from the slave trade to fund charitable works and create his bank. Within weeks of the slave trade becoming illegal, Leyland “laundered” the dirty profits from slavery into the clean and legal profits of global finance.

As slave records reveal, there was financial risk at each stage of the journey. In response to risk, Leyland was strategic. He was co-investor in several ships at a time. If any one adventure failed or sunk at sea, his investments were not all in one place. He left an extensive paper trail to record who had paid him, and who had not. His most useful tool, however, was the promissory note. Skills to manage risk, collect payment, and transport goods all equipped him with skills for the next stage of his career: from the dirty trade of slavery to the “clean” trade of banking.

Leyland later turned to public service, charitable works, and elected office. He made it is his life’s work to stamp out the unethical business practices of other Liverpool merchants in the public market stalls. As one biographer described Leyland:

There was no more strenuous supporter of the rights of the people against the oppression of the middleman than Thomas Leyland. Whether he remembered his own early struggles, or whether his sense of justice was keen, we do not know. But for the engrosser, the forestaller, the regrater he had no mercy. He, during his mayoralty of the memorable year 1814-15, made his name a terror to these evil-doers. Thomas Leyland was accustomed to visit the markets personally, and brought to justice those guilty of these offences.[20]

How do we reconcile Leyland the human trafficker responsible for thousands of deaths with his reputation as a “strenuous supporter of the rights of the people against the oppression”? Was Leyland aware of this irony? Probably not. Leyland likely never thought of his actions as wrong and immoral. Instead, it probably never occurred to him that his African captives had humanity. It remains, however, near impossible to intuit Leyland’s psychology and intentions from his records that survive. What remains clear, though, is the desire for profit.

Leyland’s letters convey a keen sense of the protestant work ethic, of frugality, of following up with customers for even the smallest expenses, and of reimbursing employees and partners for anything he owed them. In an age before standard modern banking, and in a time when most Liverpool merchants borrowed from each other, Leyland’s reputation in the community was key. A good standing in the community made for good business and built up a reputation as trustworthy. As Hughes and Rankin describe, most early Liverpool banks started as no more than a desk and ledger in a merchant’s back office:

Our predecessors were frugal, too. It was told of the above Mr. Leyland that when the Bank was in York Street and he one winter’s evening in his dwelling-house next door, a customer was ushered in. The old gentleman who was sitting in darkness assumed that the purpose of the call was to bank some belated cash, and promptly lit a candle. Finding, however, that the client had only come to discuss a loan in private, he said: ‘Ah, well, we can quite as well talk that over in the dark,’ and promptly blew the candle out.[21]

After abolition of Transatlantic Slave Trade in 1806, Leyland used profits from slave sales to establish Leyland & Bullins Bank in 1807. His partner was his nephew and fellow slave ship merchant Richard Bullin. Leyland & Bullins operated continuously in Liverpool as an independent and family-owned bank. Leyland & Bullins was then acquired in 1901 by North & South Wales Bank, which was in turn acquired by the London Joint City & Midland Bank in 1908. From about 1918 to 1934, Midland ranked as the world’s largest bank by number of customer deposits. Midland Bank built its headquarters opposite the street from the Bank of England. Midland Bank, sitting on the edge of bankruptcy in 1992, was in turn acquired by the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation.

Two centuries after slavery, the records of Leyland & Bullins are now stored in the buried archives of HSBC.[22] At each stage of the journey, money moved from account to account and bank to bank. But trace back the chain of ownership and find the slave sale that first made this wealth possible. As the conversation continues on reparations for slavery, the question remains: What is the responsibility of companies today to pay reparations for slavery?

Timeline

-

1783: Leyland’s first slave voyage

-

1806: Leyland’s last slave voyage; Transatlantic Slave Trade abolished

-

1807: Leyland & Bullins created with slave trade profits

-

1901: Merged with North & South Wales Bank

-

1908: Merged with Midland Bank

-

1992: Merged with HSBC

-

Today: The records from Leyland’s slave trading and banking operations are stored in the archives of HSBC’s British headquarters

Endnotes

[1] John Hughes, “Chapter XIV: Leyland and Bullins,” in Liverpool Banks & Bankers, 1760-1837: A history of the circumstances which gave rise to the industry and of the men who founded and developed it (London: Henry Young & Sons, 1906), pp.169-82.

[2] Biography of Thomas Leyland by British Online Archives.

[3] Sowande’ M. Muskateem, “Imagined Bodies,” in Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2016), pp. 36-54.

[4] W.P. Gray, “Watercolour of the offices of Leyland and Bullins in Liverpool, UK,” Digital Collections of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, accessed April 10, 2023, https://history.hsbc.com/collections/global-archives/leyland-and-bullins/records-relating-to-bank-buildings-2/1703841.

[5] Letter from Thomas Leyland to James Baillie of Grenada, August 13, 1788, folio 732 (page 779), accessed through Liverpool Record Office.

[6] Letter from Thomas Leyland to cloth manufacturer Mr. Rawhuson of Manchester, March 18 to 20, 1788, folio 596 (page 643).

[7] Thomas Leyland Company account books for the Jenny’s 1789-1790 voyage, University of Michigan: William L. Clements Library.

[8] Thomas Leyland Company account books for the Jenny 1792-1793, University of Michigan: William L. Clements Library.

[9] Ibid., Hannah.

[10] Letter from Thomas Leyland to Captain Charles Wilson, August 31, 1788, folio 755 (page 802).

[11] Letter from Thomas Leyland to Charles Wilson, December 9, 1786, folio 202 (page 249).

[12] Letter from Thomas Leyland to Captain Charles Wilson, August 31, 1788, folio 755 (page 802).

[13] “Sir Michael Cromie & Co.’s Ten-Guinea Promissory Note,” in Liverpool Banks & Bankers, 1760-1837, pp.160.

[14] Joshua D. Rothman, “Chapter 1: Origins 1789-1815,” in The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Slave Traders Shaped America (New York: Basic Books, 2021), pp. 9-13.

[15] Letter from Thomas Leyland to Charles Wilson, December 9, 1786, folio 202 (page 249).

[16] Letter from Thomas Leyland to William Barton of Barbados & Joseph Barton of London, August 9, 1788, folio 726 (page 773).

[17] Letter from Thomas Leyland to William Barton of Barbados & Joseph Barton of London, September 11, 1788, folio 777 (page 824).

[18] Letter from Thomas Leyland to Charles Wilson, August 4, 1788, folio 718 (page 765).

[19] Artist unkown, “Portrait of Thomas Leyland,” in Liverpool Banks & Bankers, 1760-1837, pp. 168.

[20] Ibid., “Portrait of Christopher Bullin,” pp. 174.

[21] John Hughes, “Thomas Leyland,” in Liverpool Banks & Bankers, 1760-1837, pp.174.

[22] John Rankin, “Chapter XVI: Retrospective and Discursive Reminiscences of Commercial Liverpool Sixty Years Ago,” in A History of our Firm Being some account of the firm of Pollock, Gilmour & Co. and its offshoots and connections 1804-1920, Liverpool: Henry Young & Sons Limited, 1921).

[23] “About this Collection of Leyland & Bullins,” Digital Collections of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, accessed April 10, 2023, https://history.hsbc.com/collections/global-archives/leyland-and-bullins.