At the intersection of history and the immigrant experience

Written for Kenneth Jackson’s Columbia University undergraduate course “History of the City of New York”

Mulberry Bend c.1896. Buildings on left side of street are now demolished.1

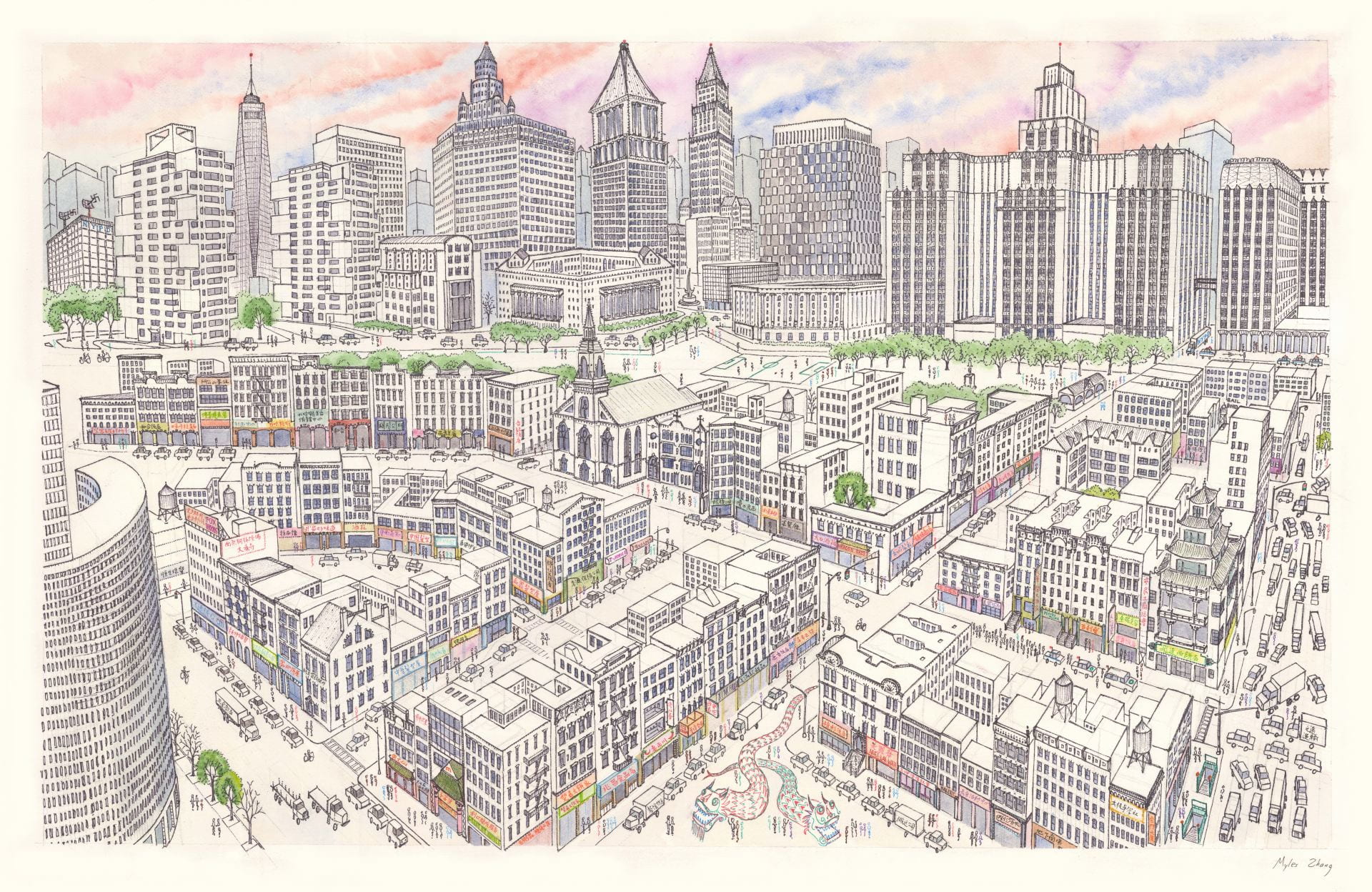

Mulberry Bend, nestled between the New York County Criminal Court and the tenements of Chinatown, is at the geographic crossroads of New York City history. At 500 feet long and 50 feet wide, Mulberry Bend is between Bayard Street to the north and Worth Street to the south. Named after the slight turn the street makes midblock, the Bend has a rich, over 350 year history: marsh, city slum, site of urban renewal, and now heart of the Western Hemisphere’s largest Chinese enclave.2 Through its rich history, the Bend’s brick and wood-frame tenements hosted waves of immigrant groups: Irish, Italians, freed blacks, and now the Chinese, one of New York’s most resilient immigrant groups whose presence in Chinatown reaches as far back as the 1830s. Consistent to these immigrant groups is their struggle to survive and prosper in America. Many of these immigrants, such as the Irish and Italians, have long left the Five Points neighborhood where the Bend is located, leaving few traces of their presence. But the neighborhood was vital as their first point of contact in the New World, a way station between their country of origin and future prosperity in the Promised Land. As such, the Bend exemplifies some of the trademarks of the immigrant experience: a working-class community populated by an immigrant diaspora that emulates the language and tradition of their country of birth. Though their homeland may be distant, in Italy, Spain, Germany, Ireland, or China, they recreated a familiar world beneath the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan. Neither fully American nor fully foreign, neither a quiet residential street nor busy commercial thoroughfare, the Bend existed and exists as a community of transient identity.

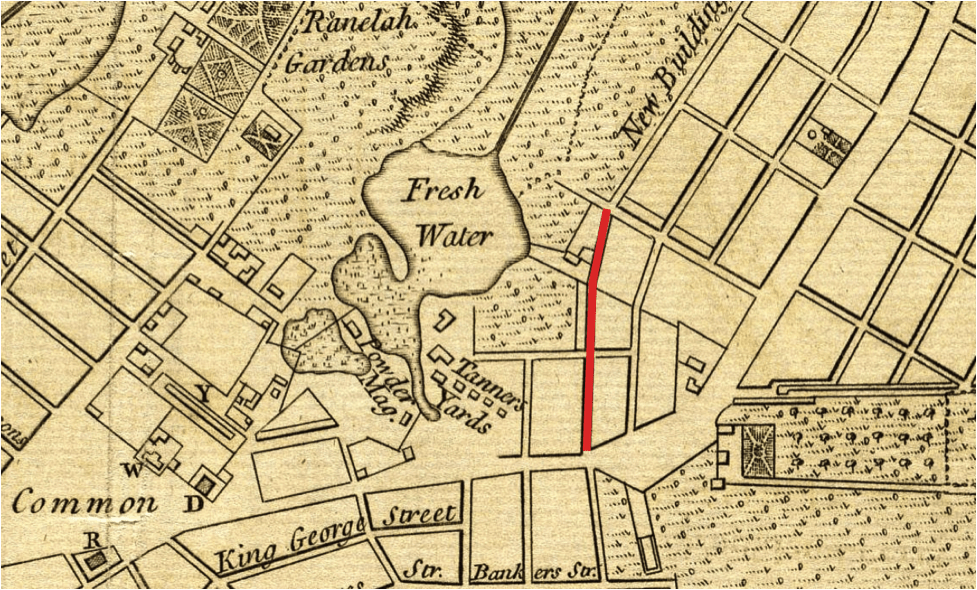

When the Dutch first settled New York, the area of Mulberry Bend and Chinatown was wooded and marshy land. The Bowery, one block east of what would become Mulberry Bend, was a Lenape Indian trail traveling from the tip of Manhattan to the heights of Harlem, about ten miles distant. The New York County Criminal Courts, one block west of the Bend, was the site of colonial New York’s main source of drinking water, the Collect Pond.3 Change came when the city’s tanning industry developed at the adjoining Collect Pond because it could carry away their industrial waste. The Ratzer Map of Manhattan, dated 1776, even plots the Bend, which bends to avoid the marshy topography of the Collect Pond. Despite this moderate industrial development and gradual filling in of the pond with soil, the area remained marshy and unfit for living.4

Excerpt from the 1776 Ratzer Map of Lower Manhattan. The area labeled as “Common” is now City Hall Park, the “Fresh Water” body was known as Collect Pond, and the “Tanners Yards” was the center of the future Five Points Slum. Mulberry Bend is the line in bright red. The dotted land pattern indicated low-lying marshes and woods that have yet to be developed. The grid of streets had been laid out, but had yet to be populated with tenements and businesses.5

After the Revolutionary War, New York prospered, first as the new nation’s capital and later as the nation’s largest city. With growth came new challenges in the Mulberry Bend. City leaders faced the difficult task of developing the marshy area. Some enterprising officials even proposed turning the area of Collect Pond into the city’s first park, designed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant, chief planner of Washington D.C.’s city plan. After all, the natural lake and rolling hills of the area could have lent themselves to scenic purposes. But in the end, economic and pragmatic concerns won out as the industrial development of the area continued and the Collect was filled in 1808. Maps from the time attest that wood frame tenements, industries, sweatshops, and breweries were built on the Bend.6

Draining Mulberry Bend solved neither the area’s pollution nor development problems. The low-lying land remained damp and muddy, a problem compounded in summer by the city’s mostly dirt and wood-plank roads. The area soon attracted some of the city’s marginalized residents, such as Blacks, prostitutes, and later the Irish after the 1840s Potato Famine. By the 1850s, the area had become the city’s disreputable slum named Five Points after the intersection of five city streets at the southern end of the Bend.7 In his 1843 visit to Five Points, Charles Dickens described the neighborhood as worse than anything he had seen in Britain; it was “reeking everywhere with dirt and filth,” concluding that “all that is loathsome, drooping and decayed is here.”8

Evidence is rich of Mulberry Bend’s historic ties to poverty and injustice. One block east of the Bend was the city’s first tenement at 65 Mott Street, a squat eight-story affair with small brick windows and no light wells. One block west of the Bend was the city’s notorious prison, nicknamed The Tombs. Though no longer surviving, The Tombs were designed by architect John Haviland in 1838 in the Egyptian Revival style.9 Due to the area’s marshy topography and the poorly covered Collect Pond, the Tombs and neighboring tenements were damp and fetid most of the year. In fact, the settling of the lowlands was so pervasive a problem that The Tombs, built of heavy granite, started sinking into the wet ground just five months post-construction. Before the advent of efficient sewer systems and indoor plumbing, the area would have been difficult to live in most of the year. Hence, independent of government intervention, the neighborhood surrounding the Bend continued to attract new waves of the poor and newly arrived who had little choice but to reside in tenements on marginal land.10

A new group arrived at Mulberry Bend beginning in the 1830s: Cantonese speaking Chinese, now some 40,000 strong. According to Mae Ngai, a childhood resident of Chinatown and now Columbia University historian of the Chinese in America, “The first Chinese came over in the early to mid 19th century as sailors or crew members in the China trade because, at the time, there was no transpacific trade through San Francisco. All cargo from China went to New York on a six-month journey around the tip of Latin America. Many were sailors and actors who chose to live in Five Points and Mulberry Bend. Many were forced to live there due to exclusionary rental policies in other parts of Manhattan.”11

Early Chinese immigrants settled on streets adjacent to Mulberry Bend, such as Mott, Bayard, Pell, and Doyers. According to Mae Ngai: “Due to the absence of Chinese women, many of these predominantly male immigrants married Irish women, who were already an established immigrant group. The Irish owned many of the Bend’s boardinghouses and flophouses frequented by Chinese sailors.” These immigrants also found niche employment in the city’s laundry business, which was an unskilled job in the era before laundry machines. The city’s laundry industry was at one time a majority-Chinese industry spread across the five boroughs and associated with New York’s Chinatown. Numbering less than a thousand at first, the Chinese population would grow in the following century, turning Chinatown into the largest Chinese enclave in the Americas.12

The neighborhood remained impoverished and a target of housing reform groups after the Civil War. From its earliest days, Five Points was the subject of significant attention from social reformers and city leaders. On the one hand, Nativists and Know-Nothings would have pointed to the neighborhood as evidence of the perils of immigrants, Catholics, the rowdy Irish, and the “filthy” Chinese. Many Protestant Americans feared the growing numbers of Catholics and Eastern European immigrants, many of whom settled near or on the Bend. On the other hand, enlightened social reformers, like abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher Stowe, would have pointed to the neighborhood as evidence of social inequity and the need for the slum reform efforts of groups like the Five Points Mission. Even Abraham Lincoln toured the Five Points Slum during his 1860 campaign for President.13

The most famous campaigner against the Bend and New York slums in general was Danish immigrant turned documentary photographer in the 1880s, Jacob Riis. Many of his most famous photographs were actually taken in the Bend, at that time occupied by the some of the worst slums in Five Points. From rag pickers to sweatshop workers and inebriated immigrants in Chinese-run Opium dens, Riis documented the deprivations and difficulties of immigrant life in bustling New York. In his now famous report How the Other Half Lives, Riis devoted an entire chapter with accompanying images just to Mulberry Bend.14

Nonetheless, Riis’ photos and method of documenting the Bend reveal prejudice against the area’s Catholic, Chinese, and other immigrant groups. As examined in later scholarship, Riis saw the poor he photographed as social menace and tried to frame their community as a criminal infested underworld. His subjects in the Bend avert eye contact with the camera lens, and his subtitles such as Bandit’s Roost and Rag Pickers’ Row sensationalize images of poverty. In his eyewitness account of photographing in an opium den near the Bend, Riis twists the account to depict the Chinese as ignorant and proud of their crimes. Chinese poverty becomes not evidence of society’s injustices against them but instead of the Chinese people’s own moral decay. How the Other Half Lives presents a biased view of Chinatown as violent, dangerous, and crime-infested.15

In reality, Five Points and Mulberry Bend were not statistically more dangerous than wealthier neighborhoods in the city. As contemporary analysis of Coroners’ Reports at the city morgue reveal, the murder rate in the Sixth Ward that included the Bend was not higher than the city average.16 Despite the higher than average numbers of foreign immigrants in this neighborhood than the rest of the city, as the 1850 Census reveals, the Sixth Ward was no more dangerous.17 But the neighborhood was largely Irish, Catholic, Italian, and Chinese, all ostracized immigrant groups that were depicted in the era’s yellow journalism as dangerous for public health and safety. Kenneth Jackson writes in Empire City: “Chinatown’s reputation had suffered in the late 1870s and early 1880s when sensationalist tabloids depicted the Chinese as opium addicts who were stealing American jobs and corrupting American women.” Considering Riis’ background as a journalist and crime photographer, his conclusions are part of this same tradition of media sensationalism.18

This does not serve to discredit Riis’ photos of Mulberry Bend or Charles Dickens’ description of Five Points; Riis’ photographs remain some of the most iconic images of the American immigrant experience. Rather viewers should be cautious when approaching these primary source documents that are not as objective as may first seem. After all, the majority of primary source documents about Mulberry Bend were created by the city’s wealthier class of White Protestant males writing about illiterate and non-native foreigners. Nonetheless, exceptions to the largely Anglo-Saxon and Protestant account of Five Points do exist such as Wong Chin Foo’s article for Puck Magazine, in which he recounts the racial prejudice faced by Chinese immigrants. In his account, he is not the aggressor or criminal on American soil so much as the victim of intolerance. As he writes: “I have been systematically styled a ‘pig-tailed renegade,’ a ‘moon-eyed leper,’ a ‘demon of the Orient,’ a ‘gangrened laundryman,’ a ‘rat-eating Mongol,’ etc.”19

Despite their problems, Riis’ damning report and poignant images of Mulberry Bend led to the creation of the Tenement Commission whose aim was the elimination of poverty and the reform of tenement building codes, both of which led to the city’s first slum clearance project at Mulberry Bend Park. After almost a century of relatively unregulated development, the area of Five Points had no public parks for school children and families. City streets, which were growing congested with traffic and hundreds of tons of horse manure per day, were not ideal places for child recreation either. City planners singled out the Bend as one of worst slums, and in a pilot project that would play out in other places across the city, they demolished the neighborhood to build Mulberry Bend Park. The park opened in summer 1897 with public fanfare and the approval of one its main proponents, Jacob Riis. Mulberry Bend Park, now known as Columbus Park, was originally nicknamed “Paradise Park,” a fitting name for what this park must have meant and felt like for people living in such a dense neighborhood deprived of any other outdoor public spaces.22

Mulberry Bend Park in 1906. Mulberry Street is at right. Original caption reads: “Mulberry Bend Park contains two and three-quarters acres of well-kept lawn. Innumerable seats, a rest house and fountains are provided for the comfort and pleasure of the people.”23

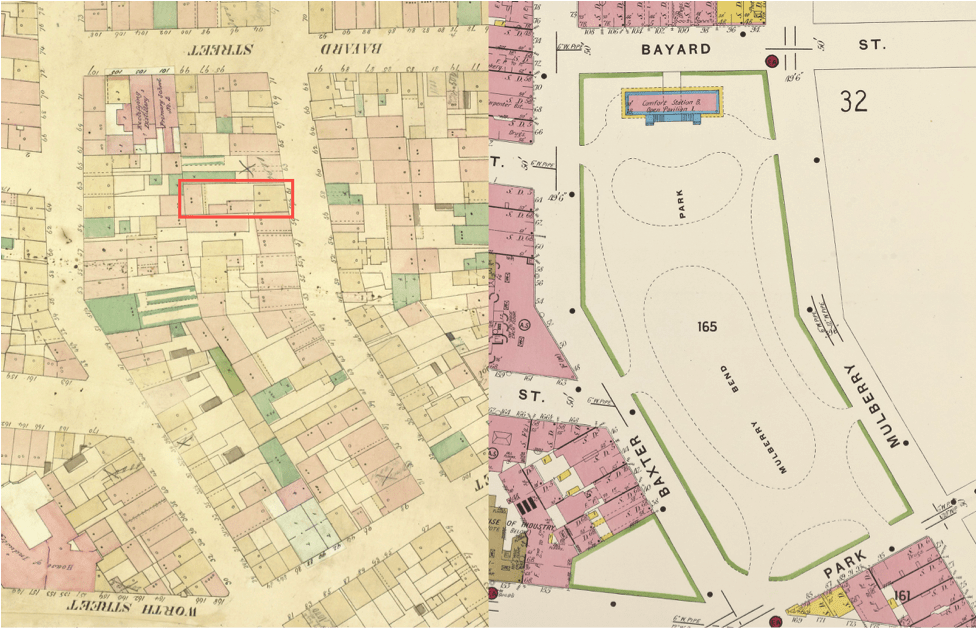

Comparative Sanborn fire insurance maps of Columbus Park in 1857 (left) and c.1905 (right). Mulberry Bend is the curved street at right between Bayard and Park. Note the replacement of hundreds of tenements and small sheds with the unified design of Calvert Vaux, one of the fathers of the City Beautiful Movement. The location of Riis’ earlier photo of Bandit’s Roost was at 59 ½ Mulberry Bend, shown in red on the 1857 map (left). A few decades later (right), few walking along Mulberry Street could have known that one of the most iconic photos in New York history was taken at this very spot. Note: Surviving buildings on the other side of Mulberry Street are not shown in the c.1905 map and were not demolished.24

The construction of a park at Mulberry Bend was the beginning of larger scale social change as New York’s government reassessed and expanded its role in civic life. In following decades, much of Five Points was demolished to construct the city’s civic center. Around 1904, the tenements southwest of Mulberry Bend were cleared to build the imposing hexagonal New York County Courthouse, built of granite to emulate a Roman temple. Similar civic and institutional structures were added in subsequent decades, such as the present New York City Hall of Records, the imposing 1930s Criminal Courts with ziggurat-like roofs, and the 1980s Metropolitan Correction Center on the site of the demolished Tombs.25

The era of Robert Moses in the 1940s and 50s brought more change to the neighborhood when tenements south of Mulberry Bend were demolished and replaced with Brutalist style government-subsidized housing. Despite the dawn of the automobile and the gradual suburbanization of American cities, Mulberry Bend remained a high-density and low-income neighborhood, occupied by growing numbers of Chinese, peaking in the year 2000 at 60,000 people. Today, the Bend remains Chinese with sounds of Chinese opera emanating from musicians in the park and the sight of the elderly playing Mahjong, a game similar to Dominoes.26 The Chinese feel of the Bend is as visible as ever.

Mulberry Bend is also notable for its several Italian funeral homes now affiliated with the Chinese. The dwindling presence of funeral bands in the area is evidence of demographic change. As of 2000, the funeral bands of the Bend were composed of Chinese and elderly Italians, a vestige of when Italians were the majority of residents in Mafia days. Of equal note is the Church of the Transfiguration around the corner, which was built for European immigrants but now serves the Chinese Christian community. The name Chinatown is a misnomer for a neighborhood that is not fully Chinese and is in many regards influenced by western culture and the footprints of past immigrant groups.27

A walk north up Mulberry Bend reveals a contrast between two visions of New York from across time. At left are Columbus Park and the imposing towers of New York’s courthouses and bureaucracies. At left is the somber wall of civic power and authority that replaced Five Points. Meanwhile, at right is the edge of Chinatown and the small five- and six-story tenements, representative of Five Points and the structures demolished to construct Columbus Park. At right is the opposite of the civic power seen at left: the living and breathing wall of an immigrant community. The Bend thus represents the physical and cultural division between two distinct New York neighborhoods, each of which embodies a different era in New York history. On one side of the park, the rundown buildings of old New York. On the other side, the oppressive and sterile towers of Lower Manhattan and a modern vision of the American city.

Chinatown illustrates the tension inherent to the immigrant experience. The immigrant to America is tied between the familiarity of their culture and language vs. the remoteness of an unfamiliar city. The immigrant finds and remains in her enclave, surrounded by fellow immigrants who speak her language, eat her food, and share her values. In the unfamiliarity of a foreign city, she finds her own community in which she attempts, however imperfectly, to replicate the values and lifestyle of the old world. Yet the foreign city of Americans and Uncle Sam is never far away. At Mulberry Bend, the towers of foreign New York City both physically and symbolically loom over immigrant Chinatown. The nearby Metropolitan Correctional Facility, city jails, and courthouses are a symbol and implicit threat that the government is gatekeeper to the opportunities of life in America. The immigrant community of Chinatown and Mulberry Street struggles onward encircled by a gentrifying city and beneath the watchful stare of the New York’s courthouses and bureaucracies.

Mulberry Bend has passed through many forms in its storied history from marshy forest on Lenape territory, to site of the city’s first drinking water and tanneries, to New York’s first and arguably worst slum, to the birth of the city’s slum clearance movement under Jacob Riis’ mixed intentions, and finally to the vibrant Chinese community visible today. For a street so small, it has witnessed so much. As gentrification displaces some residents and as younger generation Chinese choose to move away in search of better housing in the suburbs, Chinatown will continue to change. Change has been a constant in this neighborhood for three centuries. As Mae Ngai confirms: “Chinatown has never been a static place. It has always had different characteristics depending on the nature of the community.”28

Will the Bend evolve for the better or for the worse? Thousands of tourists frequent the neighborhood in search of Dim Sum and “Chinese” culture. Future changes to the demographic landscape of Chinatown should preserve the complexity of culture and the richness of history that hides just below the surface of this unassuming street and just behind the colorful facades of the walk-up tenements. Only time will tell what changes will be next.

Sources Cited

View footnotes and sources

- Jacob A. Riis, “Mulberry Bend in 1896,” digital image, Wikimedia Commons, April 17, 2011, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mulberry_Bend-Jacob_Riis.jpg#filehistory. ↩︎

- “Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps: 1857 and c.1905,” New York Public Library Digital Collections. ↩︎

- Hilary Ballon, “The Master Plan of Manhattan 1811–Now,” in The Greatest Grid, Museum of the City of New York, April 15, 2012, http://thegreatestgrid.mcny.org/greatest-grid/. ↩︎

- Hillary Ballon, The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811–2011 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012). ↩︎

- Bernard Ratzer, “The Ratzer Map of 1776,” digital image, Wikimedia Commons, April 1, 2011, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1c/NYC1776.jpg. ↩︎

- Kenneth Jackson and David Dunbar, “Collect Pond,” in The Encyclopedia of New York City, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002) 250. ↩︎

- Ibid., 414-15, “Five Points.” ↩︎

- Ibid., 186-94, “American Notes for General Circulation by Charles Dickens.” ↩︎

- Historical marker in vicinity of the Church of the Transfiguration at 29 Mott Street, “A Century of Chinese in Five Points,” October 23, 2016. In the 1830s and 1840s, many cities chose to build American civic structures in the style of Egyptian tombs and temples. The colonization of Egypt and East Asia provoked intense interest in all things “foreign” and “oriental” in both Western Europe and America. ↩︎

- Kenneth Jackson and David Dunbar, “The Tombs,” in The Encyclopedia of New York City, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002) 1190. ↩︎

- Mae Ngai, interview by Myles Zhang, Office Hours Visit at Columbia University, November 1, 2016. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Tyler Anbinder, “The Most Appalling Scenes of Destitution,” in Five Points: The nineteenth century New York neighborhood (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001) 235. ↩︎

- Jacob Riis, “Chapter VI: The Bend,” in How the Other Half Lives (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922) 59. ↩︎

- Sally Stein, “Making Connections with the Camera: Photography and Social Mobility in the Career of Jacob Riis.” Afterimage 10, no. 10 (May 1983): 9-16. ↩︎

- Sarah Paxton, “The Bloody Ould [sic] Sixth Ward: Crime and Society in Five Points, New York,” research thesis, Ohio State, 2012, https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/1811/52011/3/Bloody-Ould_Sixth-Ward.pdf. ↩︎

- U.S. Census Bureau, “1850 Census,” Table II Population by Subdivisions of Counties [and City Wards], https://www.census.gov/prod/www/decennial.html. ↩︎

- Kenneth Jackson, “Experience of a Chinese Journalist, from Puck Magazine by Wong Chin Foo,” in Empire City: New York through the Centuries,” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995) 329. ↩︎

- Ibid 230-31. The greater intolerance Chinese immigrants faced vs. the comparatively lesser intolerance faced by Irish and Italians can explain why the Chinese chose to remain in Chinatown for so long. The existence of immigrant enclaves is evidence for difficulties with social cohesion. ↩︎

- Jacob A. Riis, “59 1/2 Baxter Street,” digital image, Museum of Modern Art, http://www.moma.org/collection/works/50859?locale=en. ↩︎

- Jacob A. Riss, “59 1/2 Baxter Street.” digital image, Museum Syndicate, http://www.museumsyndicate.com/item.php?item=42895. ↩︎

- “Columbus Park,” NYC Parks Department, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/columbus-park-m015/history. ↩︎

- Jacob A. Riis, “Scenes of Modern New York,” Digital image, Wikimedia Commons, April 17, 2011, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scenes_of_modern_New_York._(1906)_(14589480310).jpg. ↩︎

- “Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps: 1857 and c.1905,” New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1857: http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e8-8021-d471-e040-e00a180654d7. 1905: http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/96e7ad32-1e9e-5c64-e040-e00a18064991. This map was incorrectly dated as 1884 in the NYPL’s database. Mulberry Bend Park was completed in 1897 and renamed Columbus Park in 1911. The actual date of this map is therefore between 1897 and 1911. ↩︎

- Kenneth Jackson and David Dunbar, “Chinese and Chinatown,” in Empire City: New York through the Centuries, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002) 215-18. ↩︎

- Jimy M. Sanders, “Chinatown: The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave,” review of Chinatown: The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave. American Journal of Sociology, July 18, 1993, 215-1, April 10, 2010, http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=socy_facpub. ↩︎

- Min Zhou, “Chinatown: The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave” (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992). ↩︎

- Mae Ngai, interview by Myles Zhang. ↩︎

Thank you for a very fascinating article. I genuinely enjoyed every word you wrote about the history of Mulberry Bend. That history is so rich and diverse. Chinatown in NYC is on my bucket list, for sure! Thanks again!