Published to my website privately, under consideration for publication in Journal of Urban History

Weequahic before the highway, 1960 |

Same view after the highway, 2023 |

.

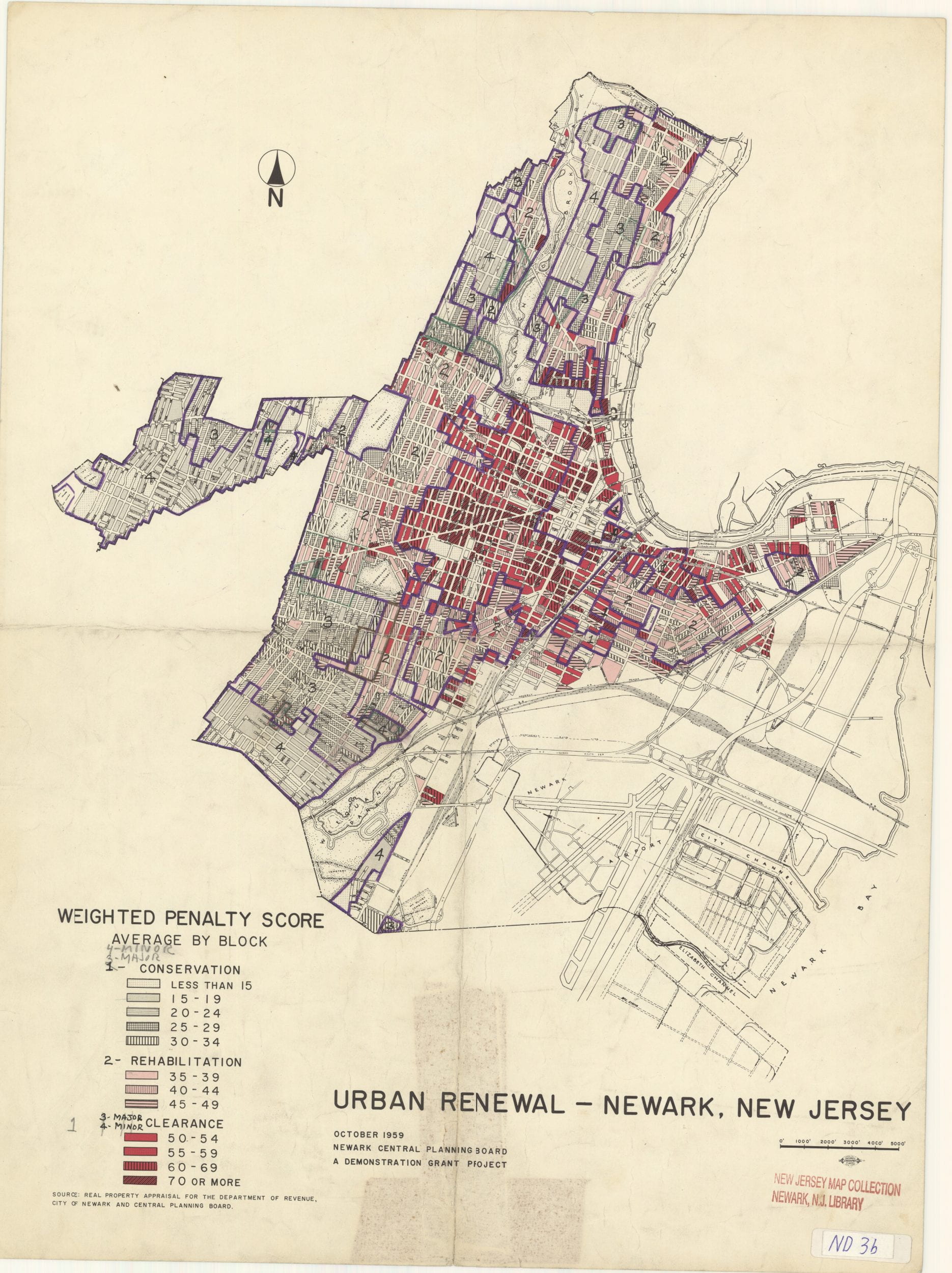

How an infrastructure project contributed to today’s urban-suburban racial wealth gap

City planners designed Interstate 78 to destroy a stable and racially integrated neighborhood of 7,500 middle-class homeowners

.

Weequahic in 1955 before the highway |

Weequahic in 2023 after the highway |

.

It did not have to be this way…

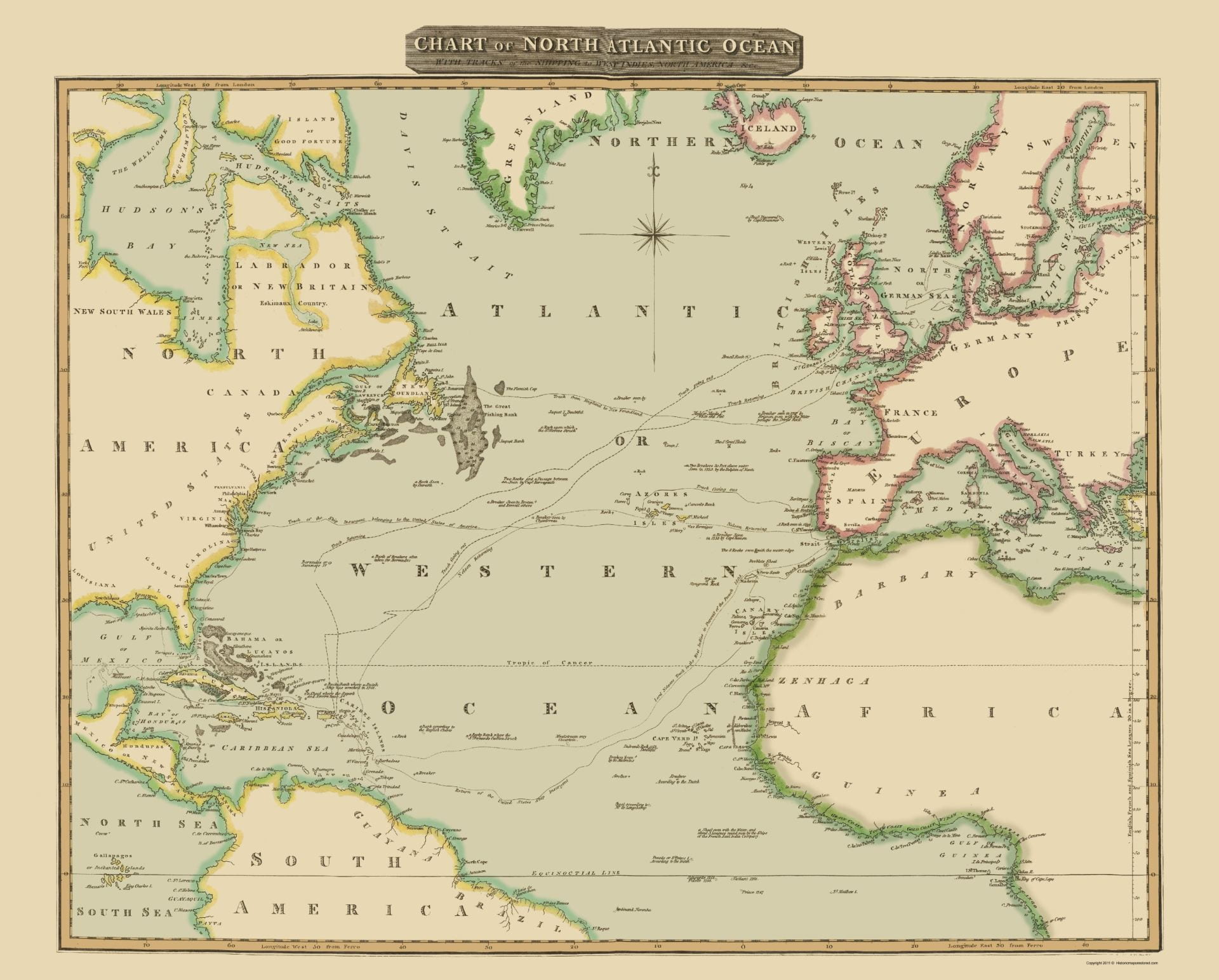

In 1958, the New Jersey State Transportation Department had a choice: Build Interstate 78 on a route that displaced some 43 families in the suburb of Hillside or build it on a path that displaced some 7,800 Jewish and black families in one of Newark’s only racially integrated neighborhoods. Engineers and planners chose the urban highway path through the Jewish and black neighborhood over the less destructive suburban route. It is a story local to Newark, but mirrored hundreds of times across the landscape of other American cities. The story of Interstate 78 is a microcosm that reveals much about the politics and inequalities of city planning in a suburban and auto age.

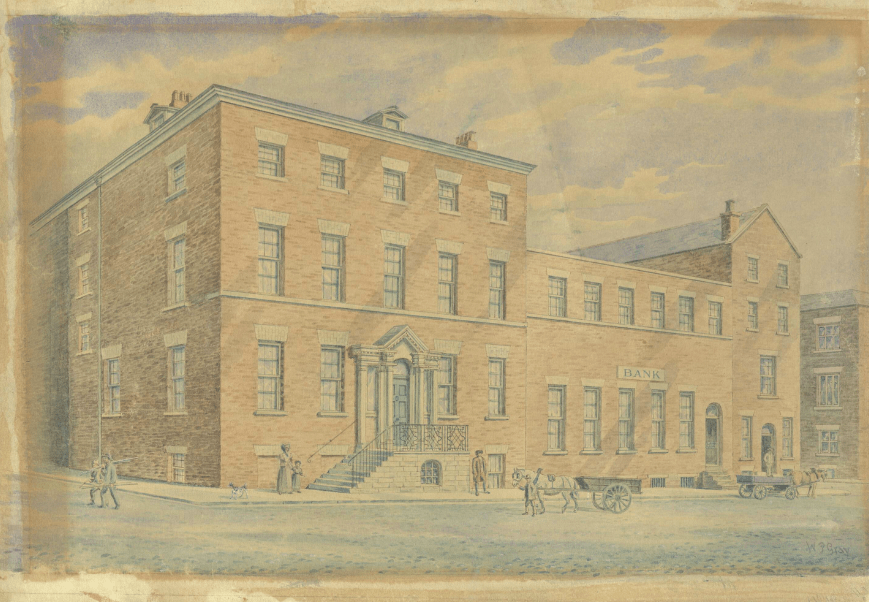

Highways slice through Newark on all sides. They cut the city into parts and divide neighborhoods from each other. The millions of cars and trucks that pass through Newark annually emit soot particles that give Newark air the highest concentration in the state of nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide. To the east of Downtown is the six-lane Route 22 built in the 1930s that divides the city from the Passaic River and restricts public access to the waterfront. To the north of Downtown is the six-lane Interstate 280 built in the 1940s. To the west of Downtown is the eight-lane Garden State Parkway built in the 1950s that divides Newark from commuter suburbs to the west. To the south of Newark is the ten-lane Interstate 78 built in the 1960s that divides Newark from historically and once majority-white suburbs like Hillside.

Collectively, these four roads box in Newark from four sides. New Jersey’s largest concentration of poverty, where the median family income is a mere $38,000, is separated from the rest of the state by a highway moat up to 400 feet wide in parts of Interstate 78. By contrast, the median family income in the Essex County suburbs that surround Newark is over $100,000. Pre-pandemic some 200,000 residents of these commuter suburbs drove into Newark on these highways, parked in Newark, made salaries on average above $50,000, and drove home at the end of each workday, leaving behind some 300 acres of surface parking lots.

It did not have to be this way.

.

Based on archival records, planning documents from the Newark Public Library, and racial redlining records from the federal government, read the full report on how the Weequahic community fought and failed to block construction of Interstate 78. →

.

Belmont Avenue in 1962 |

Identical camera angle in 2023 |

.

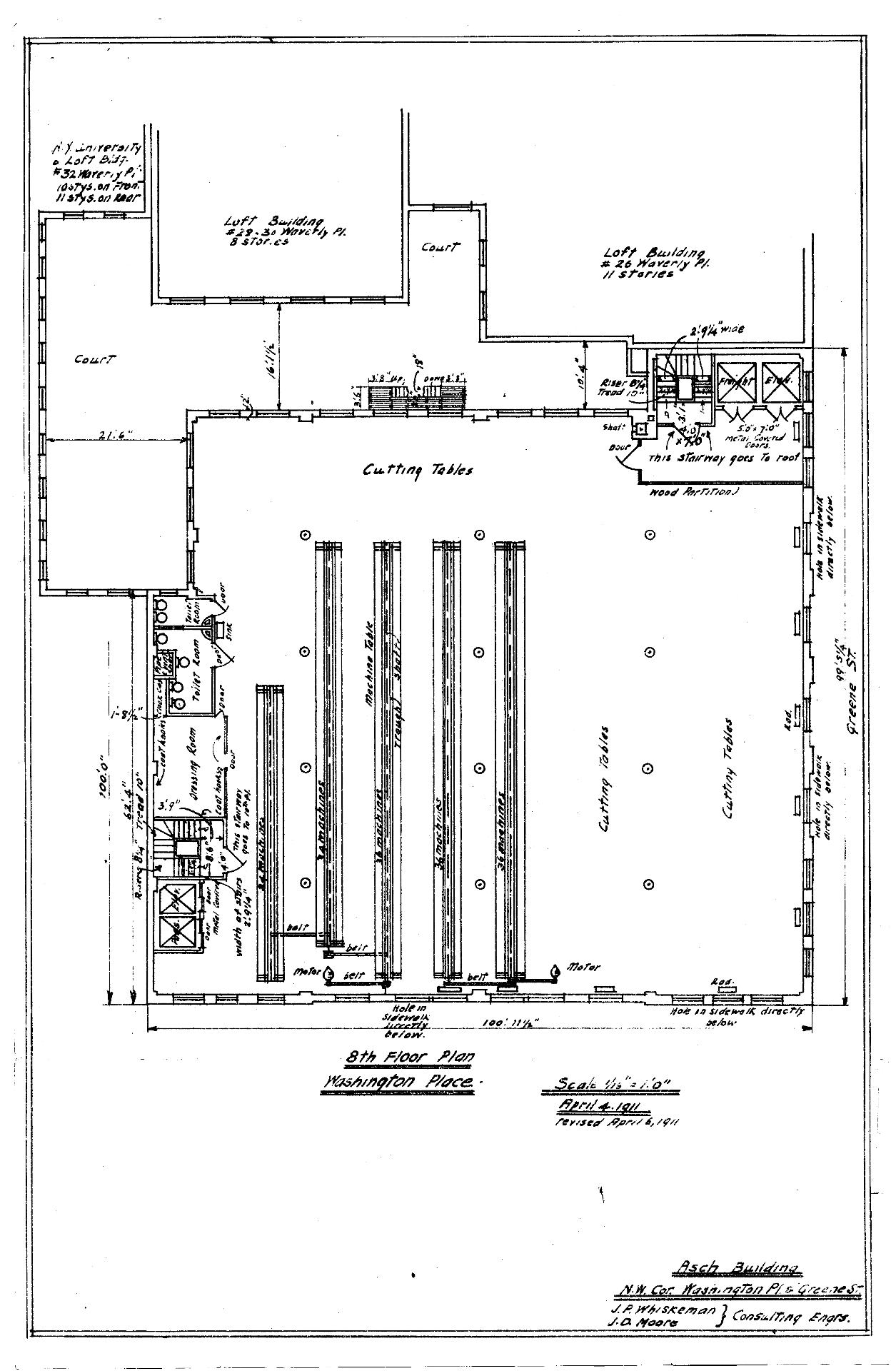

Two proposals for the path of Interstate 78

A destructive proposal from state planners vs. an alternative vision from Newark residents

.

| Proposal from State and City Planners | Proposal from Weequahic Residents | |

| Length in miles | 4.52 | About 4.7 |

| People displaced | 7,818 | Fewer than 500 |

| Demographics | 10% black | Fewer than 1% black |

| Homes demolished | 2,247 homes | 40 homes |

.

Johnson Avenue in 1961 |

Identical camera angle in 2023 |

.

1. Further viewing and interactive mapping

Photo comparisons of Newark’s Weequahic neighborhood before vs. after highway construction, in 1962 vs. today

Related publication from my website Newark Changing

2. Further Reading

For a near parallel story, see Robert Caro’s chapter on how Robert Moses drove the Cross Bronx Expressway through the Jewish neighborhood of East Tremont. In a story both local and national, Moses could have routed the highway through an adjacent park on path that would have displaced only a few hundred people. He chose the path through East Tremont, resulting in what Caro claims was the destruction of 2,000 families from a stable working class tenement neighborhood. Read more at:

Robert Caro, “Chapter 37: One Mile,” in The Power Broker (New York: Vintage Books, 1974).

3. Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my parents for their unwavering support of my studies, as well as my dissertation adviser Robert Fishman. Newark still struggles with the legacies of redlining and ongoing air pollution from its highways, port, and airport. In this fight against environmental racism, the activists at the South Ward Environmental Alliance and Ironbound Community Corporation are key actors. This history essay is written for them.

.

Jeliff Avenue in 1962 |

Identical camera angle in 2023 |

.

.

Hillside Avenue in 1962 |

Identical camera angle in 2023 |