Created at the University of Cambridge: Department of Architecture

As part of my Master’s thesis in Architecture and Urban Studies, as featured by:

.

To say all in one word, it [the panopticon] will be found applicable, I think, without exception, to all establishments whatsoever, in which, within a space not too large to be covered or commanded by buildings, a number of persons are meant to be kept under inspection.

– Jeremy Bentham

.

.

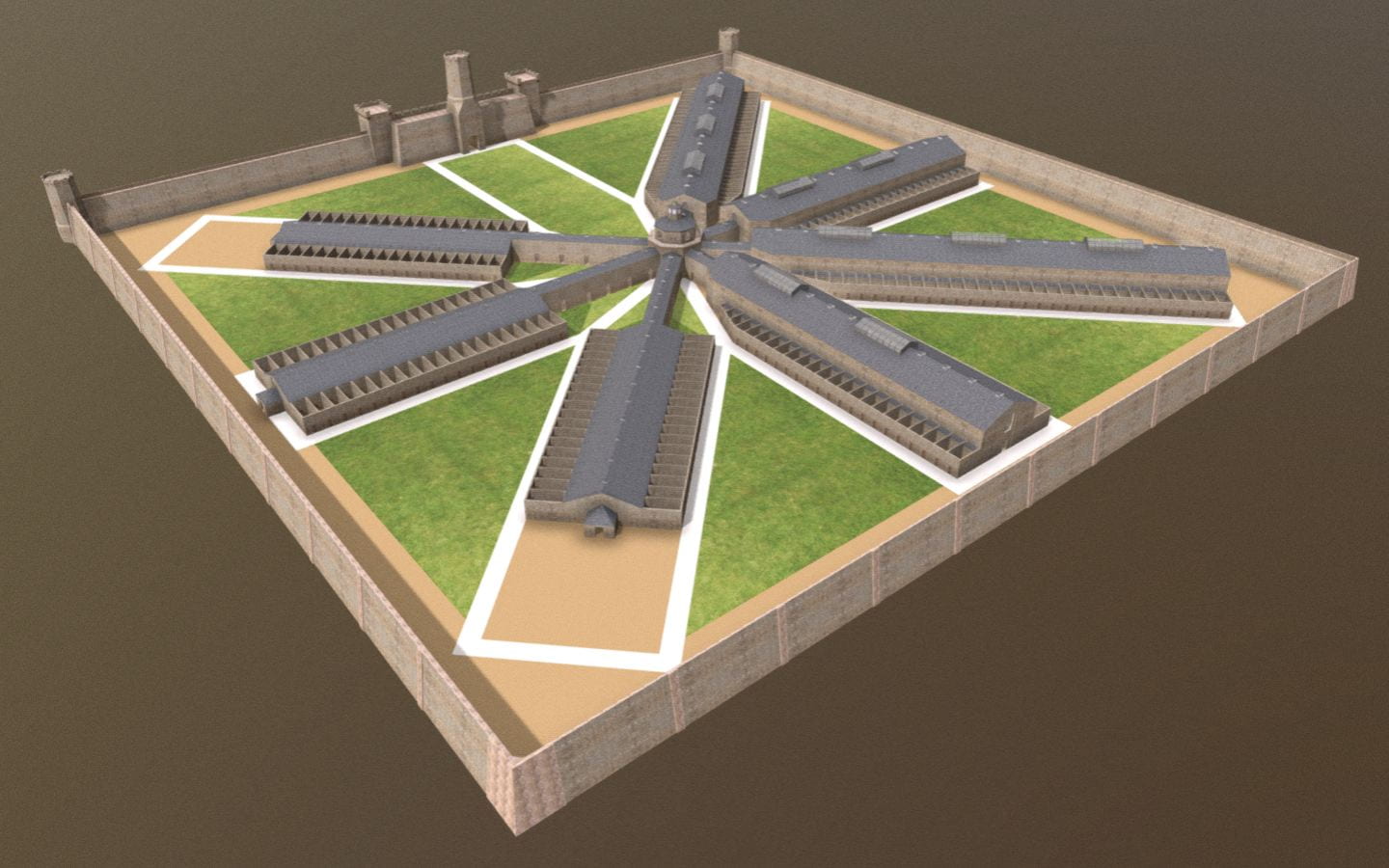

Since the 1790s, Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon remains an influential building and representation of power relations. Yet no structure was ever built to the exact dimensions Bentham indicates in his panopticon letters. Seeking to translate Bentham into the digital age, I followed his directions and descriptions to construct an exact model in virtual reality. What would this building have looked like if it were built? Would it have been as all-seeing and all-powerful as Bentham claims?

.

.

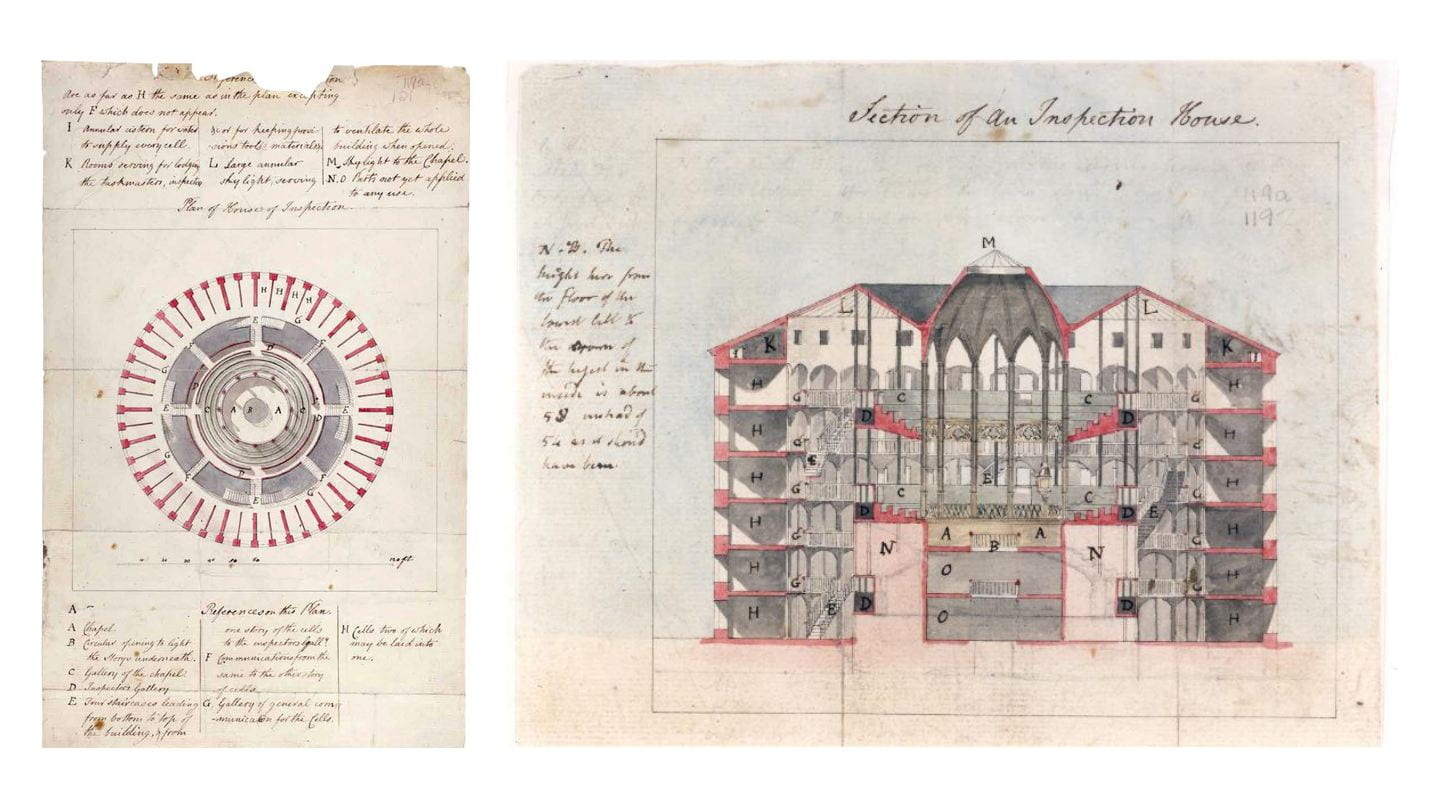

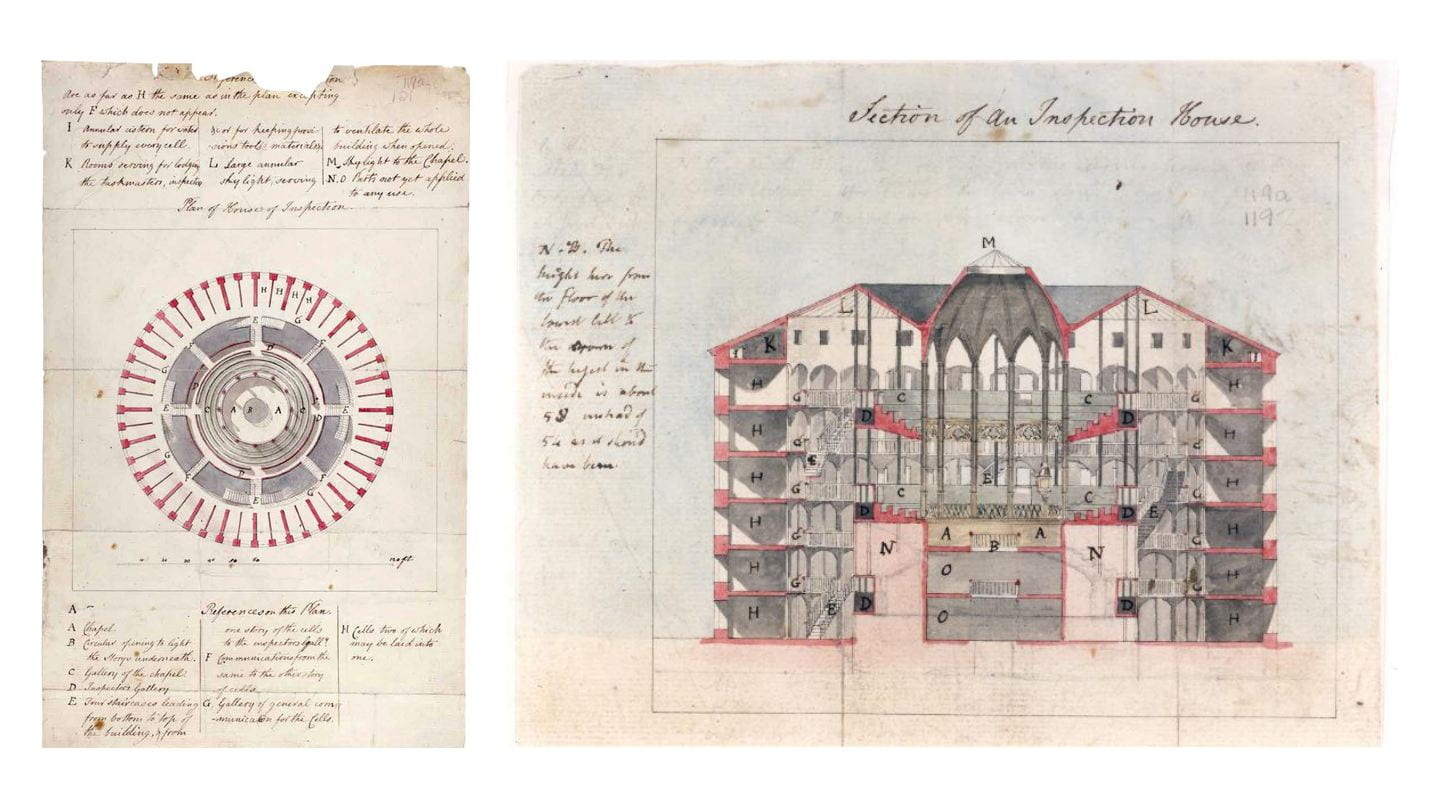

c.1791 plans of panopticon, drawn by architect Willey Reveley for Jeremy Bentham

Creative Commons image credit: Bentham MS Box 119a 121, UCL Special Collections

.

Panopticon: Theory vs. Reality

Central to Bentham’s proposed building was a hierarchy of: (1) the principal guard and his family; (2) the assisting superintendents; and (3) the hundreds of inmates. The hierarchy between them mapped onto the building’s design. The panopticon thus became a spatial and visual representation of the prison’s power relations. As architectural historian Robin Evans describes: “Thus a hierarchy of three stages was designed for, a secular simile of God, angels and man.”

.

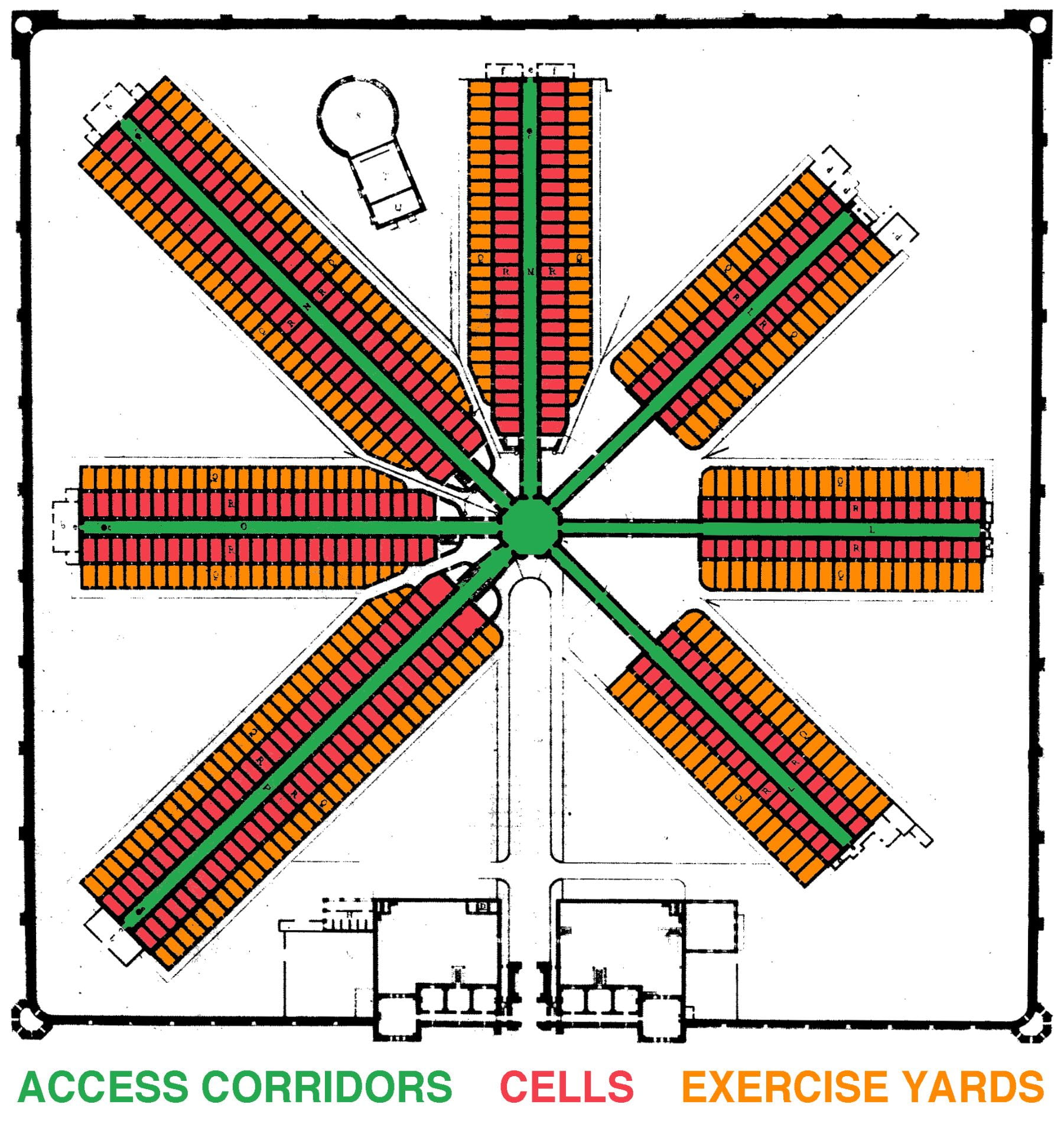

Spatial diagram of power relations

Obstructed view from ground floor

Author’s images from computer model

.

To his credit, Bentham recognized that an inspector on the ground floor could not see all inmates on the upper floors. The angle of view was too steep and obstructed by stairs and walkways. To this end, Bentham proposed that a covered inspection gallery be erected between every two floors of cells.

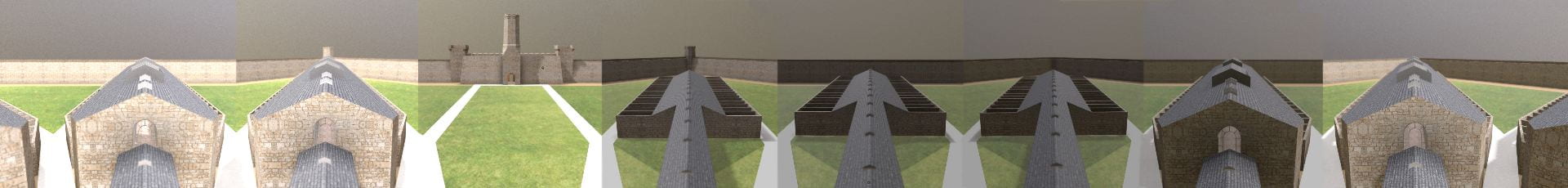

By proposing these three inspection galleries, Bentham addressed the problem of inspecting all inmates. However, he created a new problem: From no central point was it now be possible to see all activity, as the floor plans below show. The panoramic view below shows the superintendent’s actual field of view, from which he could see into no more than four complete cells at a time. The view from the center was not, in fact, all-seeing. Guards would have to walk a continuous circuit round-and-round, as if on a treadmill. They, too, are prisoners to the architecture.

.

Panopticon panorama from guard’s point of view

Section showing each guard’s cone of vision

.

Guard’s cone of vision

Guard’s walking circuit

Author’s images from computer model

.

The intervening stairwells and inspection corridors between the perimeter cells and the central tower might have allowed inspectors to see into the cells. Yet these same architectural features would also have impeded the inmates’ view toward the central rotunda. Bentham claimed this rotunda could become a chapel, and that inmates could hear the sermon and view the religious ceremonies without ever needing to leave their cells. The blinds, normally closed, could be opened up for viewing the chapel.

.

Rotunda with blinds closed

Rotunda with blinds opened

.

Bentham’s suggestion was problematic. The two cross sections above show that, although some of the inmates could see the chapel from their cells, most would be unable to do so.

In spite of all these obvious faults in panopticon design, Bentham still claimed that all inmates and activities were visible and controlled from a single central point. When the superintendent or visitor arrives, no sooner is he announced that “the whole scene opens instantaneously to his view,” Bentham wrote.

.

View from guard tower to cells: VISIBILITY

View from cells to guard tower: INVISIBILITY

.

Despite Bentham’s claims to have invented a perfect and all-powerful building, the real panopticon would have been flawed were it built as this data visualization helps illustrate. Although the circular form with central tower was chosen to facilitate easier surveillance, the realities and details of this design illustrate that constant surveillance was not possible. That the British public and Parliament rejected Bentham’s twenty year effort to build a real panopticon should be no surprise.

However flawed the architecture, Bentham remained ahead of his time. He envisioned an idealistic and rational, even utopian, surveillance society. Without the necessary (digital) technology to create this society, Bentham fell back on architecture to make this society possible. The failure of this architecture and its obvious shortcomings do not invalidate Bentham’s project. Instead, these flaws with architecture indicate that Bentham envisioned an institution and society that would only become possible through new technologies invented hundreds of years later.

.

Related Projects

.

.

Credits

Supervised by Max Sternberg at Cambridge, advised by Philip Schofield at UCL

The archives and publications of UCL special collections, Bentham MS Box 119a 121

Audio narration by Tamsin Morton

Audio credits from Freesound

– panopticon interior ambiance

– panopticon exterior ambiance

– prison door closing

– low-pitched bell sound

– high-pitched bell sound