Developed in collaboration with Newark Landmarks

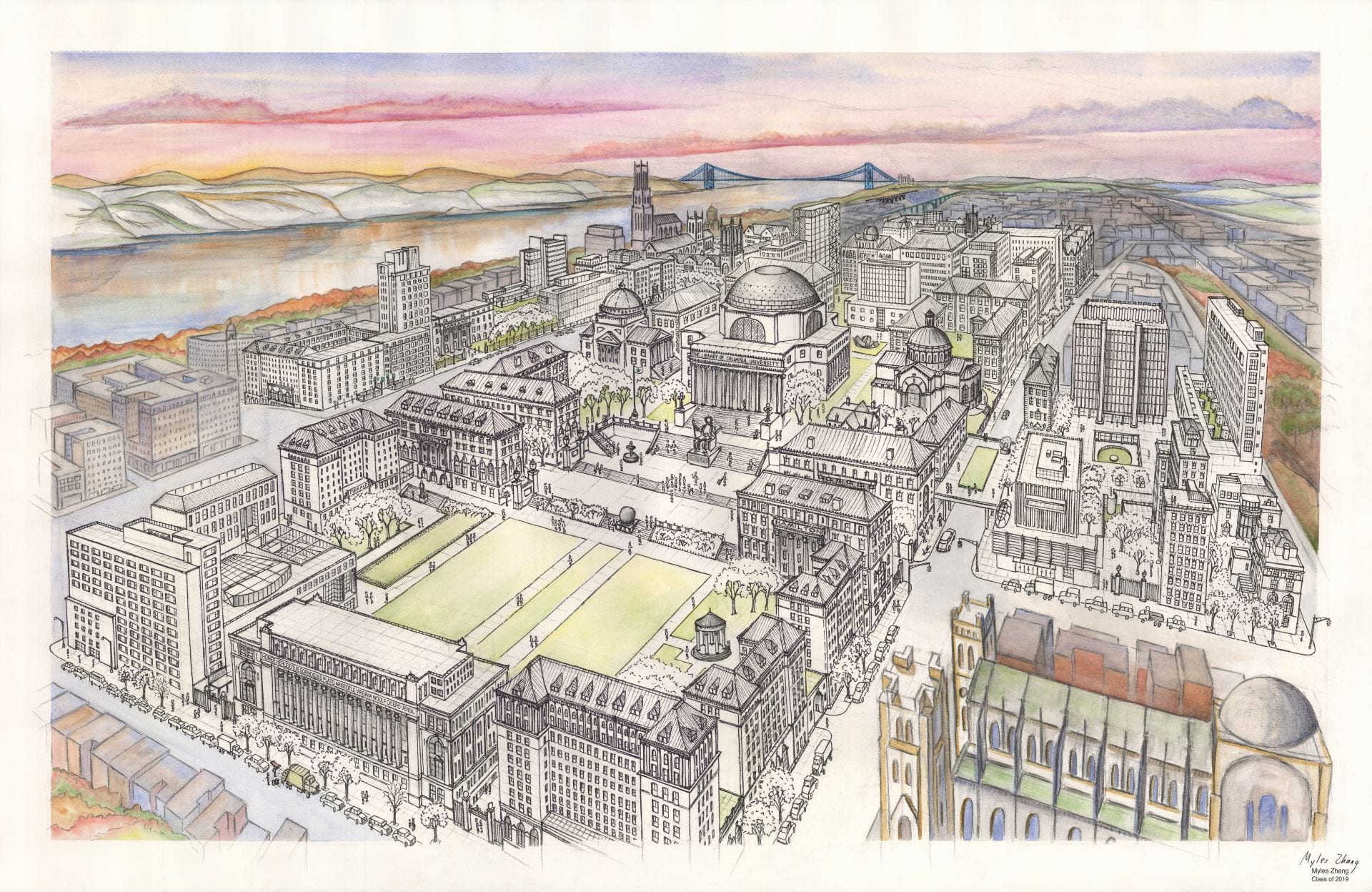

and the master’s program in historic preservation at Columbia University

.

.

Since 1971, the old Essex County Jail has sat abandoned and decaying in Newark’s University Heights neighborhood. Expanded in stages since 1837, this jail is among the oldest government structures in Newark and is on the National Register of Historic Places. The building needs investment and a vision for transforming decay into a symbol of urban regeneration. As a youth in Newark, I explored and painted this jail, and therefore feel a personal investment in the history of this place. Few structures in this city reflect the history of racial segregation, immigration, and demographic change as well as this jail.

In spring 2018, a graduate studio at Columbia University’s master’s in historic preservation program documented this structure. Eleven students and two architects recorded the jail’s condition, context, and history. Each student developed a reuse proposal for a museum, public park, housing, or prisoner re-entry and education center. By proposing eleven alternatives, the project transformed a narrative of confinement into a story of regeneration.

Inspired by this academic project and seeking to share it with a larger audience, I and Zemin Zhang proposed to transform the results of this studio into a larger dialogue about the purpose of incarceration. With $15,000 funding from Newark Landmarks, I translated Columbia’s work into an exhibition. I am grateful to Anne Englot and Liz Del Tufo for their help securing space and funding. Over spring 2019, I collaborated with Ellen Quinn and a team at New Jersey City University to design the exhibit panels and to create the corresponding texts and graphics. The opening was held in May 2019, and is recorded here.

.

.

My curator work required translating an academic project into an exhibit with language, graphics, and content accessible to the public. Columbia examined the jail’s architecture and produced numerous measured drawings of the site, but they did not examine social history. As the curator, I shifted the exhibit’s focus from architecture to the jail’s social history – to use the jail as a tool through which to examine Newark’s history of incarceration. As a result, much of my work required supplementing Columbia’s content with additional primary sources – newspaper clippings, prison records, and an oral history project – that tell the human story behind these bars. I worked with local journalist Guy Sterling to interview former jail guards and Newark Mayor Ras Baraka about his father’s experience incarcerated here during the 1967 civil unrest. The exhibit allowed viewers to hear first-hand accounts of prison life and to view what the Essex County Jail looked like in its heyday from the 1920s to 1960s. Rutgers-Newark organized seminars connected to the jail exhibit on the topic of incarceration in America, and what practical steps can be taken to change the effects of the growth of incarceration.

The finished exhibit was on display from May 15 through September 27, 2019. The exhibit makes the case for preserving the buildings and integrating them into the redevelopment of the surrounding area. The hope is that, by presenting this jail’s history in a public space where several thousand people viewed it per week, historians can build support for the jail’s reuse. Over the next year, an architecture studio at the New Jersey Institute of Technology’s College of Architecture and Design is conducting further site studies. Before any work begins, the next immediate step is to remove all debris, trim destructive foliage, and secure the site from trespassers. These actions will buy time while the city government and the other stakeholders determine the logistics of a full-scale redevelopment effort.

My interest in prisons drew me to this project. This jail’s architect was John Haviland, who was a disciple of prison reformers John Howard and Jeremy Bentham. In my MPhil thesis research about Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary, I developed my exhibit research by looking at the social and historical context of John Haviland and early prisons. As I describe, Eastern State began as a semi-utopian project in the 1830s but devolved by the 1960s into a tool of control social and a symbol of urban unrest.

.

Launch Virtual Exhibit Website

.

.

Related content

-

Read my January 2021 article in The Newarker magazine.

-

Read this July 2020 article from Jersey Digs

about my exhibit and the New Jersey Institute of Technology’s proposal to reuse this jail site. -

Hear my September 2019 interview about this jail and exhibit from Pod & Market.

-

Explore this jail as an interactive exhibit online.

-

View this artwork as part of my short film from 2016 called Pictures of Newark.