Data analysis of NYC landmarks since 1965 reveals trends and biases in the landmarks preservation movement.

Developed with urban historian Kenneth Jackson at Columbia University’s Department of History

.

.

A visual history of landmarks preservation in NYC. Data from NYC Open Data. Music from Freesound.

.

Introduction

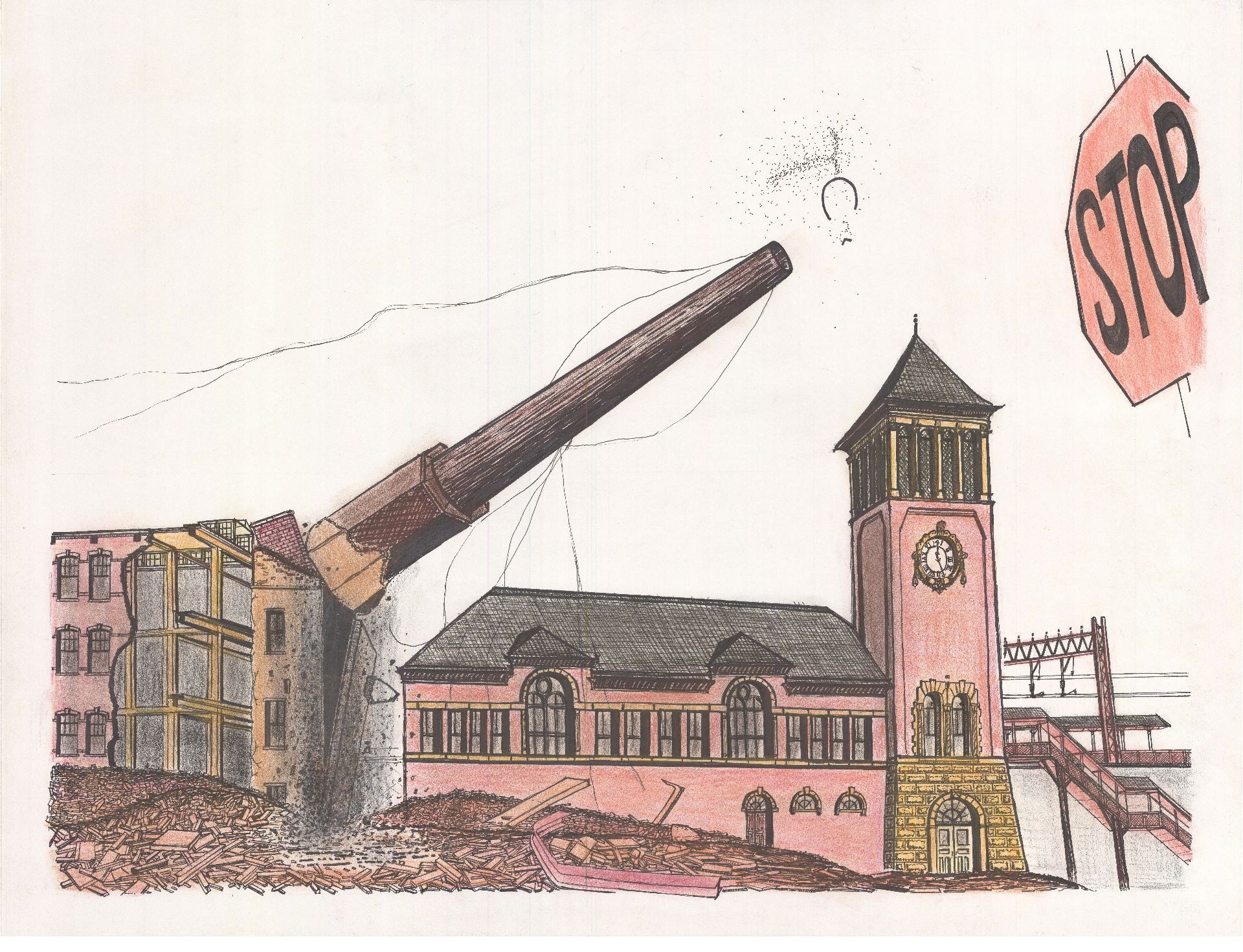

There is ongoing debate between in NYC between developers seeking to rebuild the city in the image of global capitalism and preservationists seeking to slow the rate of change and protect the appearance of the city’s many and distinct neighborhoods. Several factors drive historic preservation: fear of losing heritage; fear of change; historians, public servants, and well-intentioned activists in the spirit of Jane Jacobs. This debate has played out every year since 1965 through the hundreds of structures that are added to (or rejected from) the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s running list of landmarks (LPC). Once added, landmarked buildings cannot be modified without first seeking approval from the city. Landmarks preservation is contentious for developers because the protections of preservation law are permanent and affect all current and future owners. Preservation law further restricts significant rebuilding, even if demolition and rebuilding are lucrative for the property owner.

Historians decide the future of the city’s built environment. The sites they preserve will become the architectural lens through which future generations will appreciate the past. The sites they approve for demolition will be lost to history. Preservation is a response to larger historical questions: Which aspects of the past are worth preserving? How should the city balance the economic need for development with the cultural need for history?

This paper will assess the landscape of historic preservation through analysis of publicly-available landmark records from NYC Open Data. We identified two datasets, both containing ~130,000 spreadsheet entries for every single LPC listing from 1965 to 2019. The first dataset is titled “Individual Landmarks” 1 and includes the structure’s address, lot-size, and date landmarked. The second dataset is titled “LPC Individual Landmark and Historic District Building Database” 2 and includes the construction date, original use, style, and address of all structures. We downloaded both datasets as .csv files, imported them into a visualization software called Tableau, merged them into a single map, and then analyzed the data. The results of inform the conclusions presented here. This analysis is broken into four case studies:

-

Distribution of Landmarks over the Five Boroughs

Assesses where landmarks preservation is densest or least dense by neighborhood. -

Contextual Preservation?

Analyzes how protecting a landmark limits redevelopment of neighboring properties of less aesthetic value -

How does the preservation movement reflect economic patterns?

– Factor affecting the preservation of city-owned structures

– Factors affecting the preservation of residential structures

– Relationship between preservation and gentrification?

-

Keeping up to pace?

Questions the degree to which landmarks preservation succeeds in protecting recently-built landmarks

From this data, hidden trends and biases in historic preservation become visible. Firstly, we identify a higher-density of landmarks in certain (and usually higher income) neighborhoods. Secondly, we identify a marked preference among historians for protecting structures pre-1945. (Is there so little in the city’s recent architectural history that is worth preserving?) And thirdly, our analysis hints at the strength of market forces and developers in shaping the scope and definition of preservation.

Read More

.

- “Individual Landmarks,” NYC Open Data, https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Housing-Development/Individual-Landmarks/ch5p-r223 (retrieved 5 November 2018). ↩

- “LPC Individual Landmark and Historic District Building Database” NYC Open Data, https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Housing-Development/LPC-Individual-Landmark-and-Historic-District-Buil/7mgd-s57w (retrieved 5 November 2018). ↩

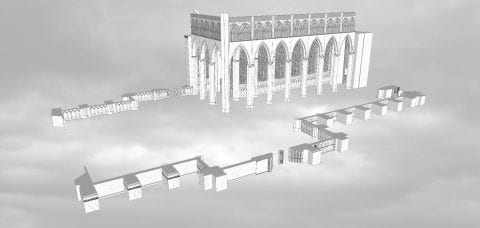

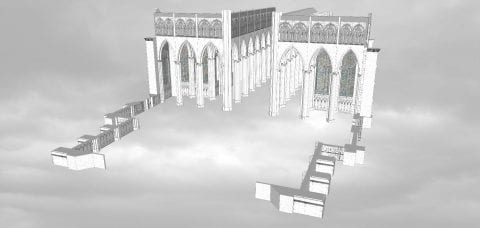

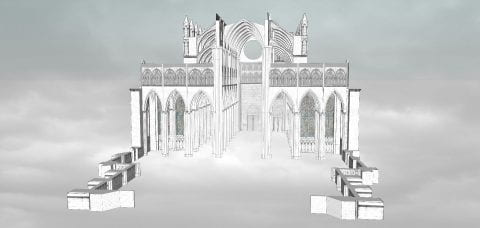

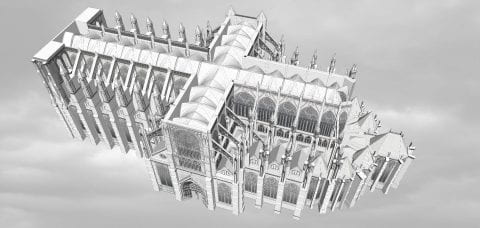

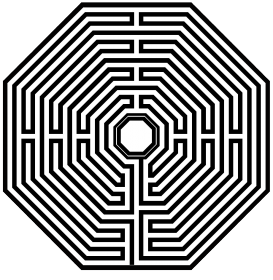

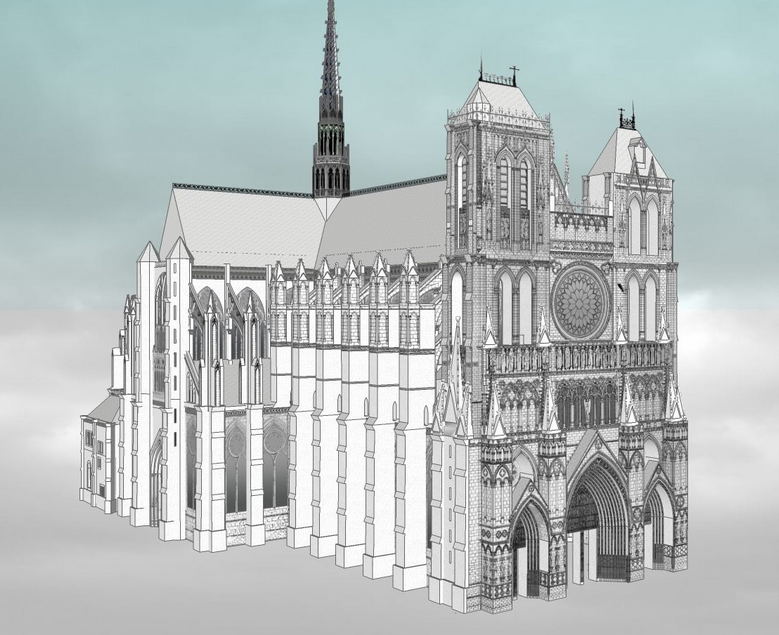

Along with the Parthenon, Amiens Cathedral is introduced each semester to students in Art Humanities. This seminar has been taught since 1947 and is required of all undergraduates as part of the Core Curriculum. Through broad introductory courses in art, literature, history, music, and science, the Core aims to produce well-rounded citizens of Columbia University students. Amiens was chosen as representative of all Gothic architecture, and as a lens through which to teach skills of visual analysis. This computer model I created instructs over 1,300 students per year.

Along with the Parthenon, Amiens Cathedral is introduced each semester to students in Art Humanities. This seminar has been taught since 1947 and is required of all undergraduates as part of the Core Curriculum. Through broad introductory courses in art, literature, history, music, and science, the Core aims to produce well-rounded citizens of Columbia University students. Amiens was chosen as representative of all Gothic architecture, and as a lens through which to teach skills of visual analysis. This computer model I created instructs over 1,300 students per year. A building is experienced as a sequence of sights and sounds. A research text about such a building, however, can only capture limited information. Photography, film, and computer simulations are, in contrast, dynamic and sometimes stronger mediums to communicate the visual and engineering complexity of architecture. This project seeks to capture dynamic Amiens through a visual, auditory, and user interactive experience. Through film, one can recreate and expand the intended audience of this architecture, recreating digitally the experience of pilgrimage.

A building is experienced as a sequence of sights and sounds. A research text about such a building, however, can only capture limited information. Photography, film, and computer simulations are, in contrast, dynamic and sometimes stronger mediums to communicate the visual and engineering complexity of architecture. This project seeks to capture dynamic Amiens through a visual, auditory, and user interactive experience. Through film, one can recreate and expand the intended audience of this architecture, recreating digitally the experience of pilgrimage.