.

Soundtrack: “Pruitt Igoe” from Koyaanisqatsi, directed by Godfrey Reggio and composed by Philip Glass.

.

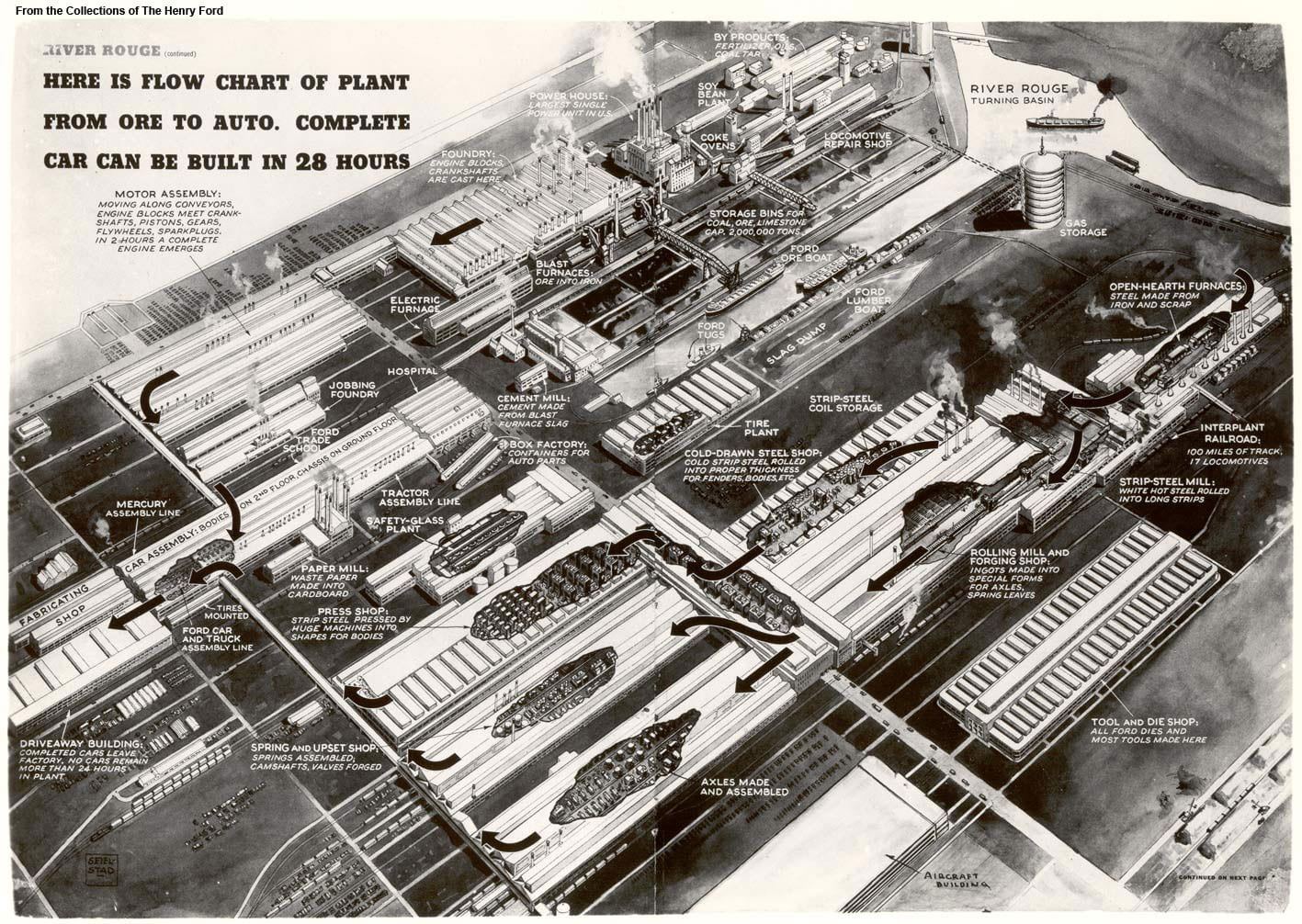

This film traces Detroit’s evolution from its origins as a French trading post in the 1700s, to its explosion as a metropolis, followed by its precipitous decline as a symbol of America’s post-industrial urban landscape. The film weaves in details about the city’s politics, population, and technology – all of which influenced the city’s geography and built environment. At each phase in urban history, the built environment grew and was modified in direct response to political events like racial segregation, population changes like the Great Migration, technology developments like the mass-produced car, and government interventions like urban renewal.

The animation tells the story of Detroit specifically and the story of American cities more broadly. To varying degrees, the path of Detroit’s development mirrors hundreds of other smaller cities and towns scattered across the American Northeast and Midwest. No other American city witnessed as large a population loss, as dramatic 1960s racial unrest, or as radical a transformation from symbol of progress into symbol of decay. To a lesser degree, other places in America followed Detroit in lockstep. Urban renewal projects, highway construction, racial tensions, suburban growth, and infrastructure under-investment happened across America, and in parallel to Detroit.

However, the most dramatic transformation of Detroit is left unwritten in this film. Beneath the surface-level events of political conflict and urban change, the largest event in Detroit is not unique to Detroit. As filmmaker Godfrey Reggio describes, the most important theme in the history of civilization is “the transiting from all nature, or the natural environment as our hosts of life for human habitation, into a technological milieu into mass technology as the environment of life.” European cities developed slowly and gradually over centuries, in the process removing all memory of the natural landscape before civilization. American cities are unique in their youth and speed of growth. They are new enough that an active memory survives through place names and written records of the landscape and indigenous peoples who lived there before colonization. As the oldest colonial settlement west of the Appalachians, and as the city that perfected the mass-produced automobile, Detroit becomes the prime symbol of man’s transformation of his home from a natural world into a technological society removed from nature.

Includes links to download all source files on which the film is based

.

The accompanying music is by composer Philip Glass and was written for Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 experimental documentary Koyaanisqatsi. The shifting layers and repetitive phrases of Glass’ music accompany Reggio’s montages of natural landscapes, factory assembly lines, and chaotic city streets. Koyaanisqatsi means “life out of balance” in the language of an indigenous American tribe called the Hopi. In the original documentary, Glass’ music was paired with scenes of desolate streets in the South Bronx, the abandoned Pruitt-Igoe public housing in St. Louis, and ruined skyscrapers falling in slow motion. In my reinterpretation of Glass’ music, the imagery is now of Detroit in maps. The pace and events in the animation are tied to the structure of the music. As the volume and speed of the music increase and decrease, so too does the growth and decline of Detroit.

Pruit Igoe from Koyaanisqatsi; composed by Philip Glass with images by Godfrey Reggio

.

Population Changes to Detroit Over Time

Hover over infographic for details of each census year.

.

The influx of Black people during the Great Migration and the outflow of cars from Detroit’s factories reshaped the city’s built environment and the American public’s perception of Detroit. Detroit is now thought of as a majority-Black city surrounded by majority-White suburbs. Today, 83% of Detroit’s population is Black, and only 11% is White. But the graph above shows that Detroit was majority-White until the 1980 census. For most of its history, Detroit was 95 to 99% White. Today, the majority of the metro region’s population lives in the suburbs that surround Detroit. But until the 1960 census, the majority of the population lived within the city limits. Today, Detroit is so reliant on the car that it has no commuter rail network, no subways, and limited public transportation options. But until the 1950s demolition of Detroit’s light rail network, a majority of residents lived within walking distance of a light rail station for commuting. Detroit’s demographics, suburban sprawl, and transportation options have all flipped in the past century. From a high-density, transportation rich, and majority-White city in 1920, Detroit has become a low-density, transportation poor, and majority-Black city in 2020.

A lot of people say Detroit has terrible public transit design. But from the perspective of car companies, the real estate lobby, and fearful Whites, the system does exactly what it was intended to do: to segregate and divide our country by covert means long after Jim Crow officially “ended.” Failure by design. The failure of Detroit is, in large part, planned and a consequence of government policy decisions that: prioritize suburban growth over urban development; benefit suburban Whites over urban Blacks; and encourage private cars at the expense of public transit.

As the Detroit Evolution Animation plays, the map key on the lower right hand corner indicates Detroit’s demographics at each decade in history. Try to link changes to demographics with changes to the urban form. Ask yourself the questions: How were technology, transportation, and demographic changes imprinted on the built environment? How does the built environment, in turn, shape urban and suburban life?

.

Decaying home near Detroit’s abandoned Packard Automotive Plant

Left to right: lights from Newark, Detroit (Fox Theater marquee), and Santander (Spain)

Left to right: lights from Newark, Detroit (Fox Theater marquee), and Santander (Spain)