The construction of Notre-Dame mirrors the larger story of the French nation.

Medieval France was splintered into regional kingdoms and alliances between local feudal lords. In the tenth century, the Capetian rulers in central France started consolidating power and lands. Through conquest, marriage, and diplomacy, the Capetians expanded their influence first to Paris and then outward. By the thirteenth century, the Capetians controlled most of the land within the present-day borders of what is now France. Over this Catholic kingdom, they ruled generation after generation in centuries of uninterrupted rule until the French Revolution.

While the Capetians did not start as the largest and most powerful kingdom in Europe, they soon amplified their power through alliance with the church. From Reims Cathedral (where all Capetians were crowned) to the Church of St. Denis near Paris (where they were all buried), the French monarchs asserted power through their relationship with the church. They claimed their right to rule descended from God’s mandate. God himself ruled through and expressed his demands through the soul and mind of the king. To oppose the king would therefore be to oppose the wishes of God.

The construction of Notre-Dame of Paris was therefore a project for the Capetian kingdom in the capital city of Paris. With the monarchy’s control of France’s largest and most important trade center, the cathedral became a central symbol of the power of the city and the kingdom. From across Europe and France, other peoples looked to Notre-Dame for design inspiration. The model and building techniques of Notre-Dame were copied far and wide. Paris might have had limited geographic borders, but through the churches and monasteries in other regions that looked to Paris for aesthetic inspiration and theological guidance, Paris wielded a soft power to influence culture.

.

Expansion of the Capetian lands from 987 to 1223. Arrows radiating from Paris point to the cathedrals inspired from Paris and Saint-Denis.

The blue area shown in 1154 shows the competing empire from the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to King Henry II. The orange lands shown in 1223 are fiefdoms dependent upon the French Crown under king Philip Augustus. Animation from Stephen Murray at Mapping Gothic France.

.

Among medieval cathedrals known to take centuries to complete, Notre-Dame was finished in short time. In just eight decades from c.1160 to c.1245, Notre-Dame emerged from the rubble in the completed form the public would recognize it today. Soon, neighboring towns in competition with Paris began erecting larger and taller cathedrals of their own. Among them, the powers centered on the cities of Chartres to the southwest, Amiens to the north, and Rouen to the northwest expressed their competition with Paris through their grander cathedrals. Not to be outdone, from 1220 to 1225 the Parisians rebuilt the entire upper levels and vaults of Notre-Dame to be taller, more luminous, and more ornate than before. The powers at Chartres, Amiens, and Rouen were soon crushed in battle and became the allies of an increasingly centralized French empire.

The public interprets cathedral construction as an act of devotion to God. The fine materials, craftsmanship, and physical challenges of construction symbolize the builders’ devotion, or gratitude for God listening to their prayers. The more expensive the project and the more difficult the construction, the greater the finished cathedral becomes as a symbol of sacrifice. Medieval stories often speak of the devout paying penance for their sins by dragging carts of heavy cathedral stones from quarry to building site. Or when the cathedrals faced structural collapse, natural disasters, and frequent fires, builders and clergy read these events as God expressing his dissatisfaction that their project was not good enough.

Less often does the public see the sacred built environment as an expression of political power, or as a tool of diplomacy and nation building. For the church to somehow be caught up in earthly affairs of wealth building, land investments, tax collection, and power squabbles seems vulgar and a distraction from the higher sacred mission. Cathedral construction required massive fundraising and tax collection efforts, the mobilization of thousands of laborers, and the sale of indulgences (donations to the church in exchange for certificates promising to reduce the donor’s punishment in the afterlife). As Notre-Dame of Paris reveals, construction cannot be separated from larger political events.

At every step in the history of the Capetians, monarchs sponsored building projects and used their power to carry out the political agenda of the church. Louis IX was made a saint for leading the Crusades to retake the Holy Land and its trade routes from Islam. The Sun King Louis XIV relied on the papal Cardinal Mazarin during his earliest years in power. And the ill-fated Louis XVI refused to share the monarchy and church’s monopoly on power with the people, causing the middle and working classes to wage the French Revolution.

The French Revolution asserted that government’s right to rule does not descend down from God and the church, as monarchs had claimed for centuries. Instead, political legitimacy flows up from the people, their right to vote, and their support for the elected government. Skepticism in the religious basis for political power, coupled with the Enlightenment belief that science and human reason alone can unlock social progress and the project of democracy, re-centered society on a new foundation. Church and state were separated, and with that Notre-Dame fell into a half-century of decay and abandonment.

In the French Revolution, Notre-Dame and hundreds of other French churches were abandoned, desecrated, and often demolished for the value of their building materials. Notre-Dame was confiscated from the church and transformed into a “Temple of Reason,” while most of its statuary was destroyed. The statues of 28 Biblical kings on Notre-Dame’s west façade were mistaken as French because their robes were modeled after Capetian kings. And so they were pulled down with ropes and decapitated by the mob in the city square. Not until the mid nineteenth century was Notre-Dame restored by Viollet-le-Duc with a new spire, new windows, new carvings, and restoration efforts sometimes so extensive that the cathedral surviving today is as much a product of the medieval era as it is a nineteenth-century creation. Notre-Dame began to emerge as a symbol of the French culture, identity, and nation.

Notre-Dame’s fire on 15 April 2019 reminded the public once again of architecture’s role in shaping and symbolizing national identity. The fire was as much a loss of architecture and cultural heritage as it was a threat to the French identity. The cathedral’s fire-damaged vaults and wooden roof turned to ashes symbolized an interrupted continuity with history. The cathedral had survived hundreds of years through plague, world wars, and revolution, as if symbolizing the continuity and purity of the French language, culture, and history. And now this link with history and the origins of the modern French nation was severed.

The efforts to rebuild Notre-Dame “as it was before” reveal the larger misconception that there is such a thing as a pure and original state. Pre-modern builders and patrons interpreted fires and natural disasters as innovation opportunities to rebuild what was lost as bigger and better than before, and often with the latest building techniques and architectural style. The church that stood at the site of future Notre-Dame, and which was demolished to build the current cathedral, was itself hundreds of years old and dating back to the late Roman Empire. And yet medieval audiences demolished it all the same with the confidence that what they built would be better than what was there before. Past generations at Notre-Dame viewed the cathedral and history as something fluid that could be embellished and improved through cycles of demolition. As late as the nineteenth century, Viollet-le-Duc imagined and added new details to the cathedral that never, in fact, existed.

Just days after the fire, architects submitted dozens of proposals to rebuild the site. Preservationists instead decided to rebuild the cathedral with the same pre-modern techniques, materials, and interior wooden roof trusses. Is contemporary art and culture so impoverished of beauty that contemporary society is incapable of enriching Notre-Dame with the building techniques and aesthetics of the modern era? Do we no longer believe in the forward path of progress, and must therefore pause the appearance of Notre-Dame the way it was?

The fire revealed that there are, in fact, two cathedrals: the physical cathedral built as a symbol of the French state and faith; and then the cathedral of our memories, with all the personal meanings visitors drew from their experience of the space. The two cathedrals are not the same because the meanings and symbolism we assign Notre-Dame in our memories are different from the cathedral’s intended purpose. The medieval clergy and kings never intended to create a symbol of the modern French state, of Victor Hugo’s literature, or of international Christianity. Yet Notre-Dame’s ability to acquire new meanings and identities through time speaks to the fact that this cathedral is a living work of art. With or without the physical cathedral, the Notre-Dame of our imaginations, of art, of literature, and of the millions of souvenir photographs will continue to live. At least in the collective imagination, Notre-Dame is immortal.

.

Fire on 15 April 2019

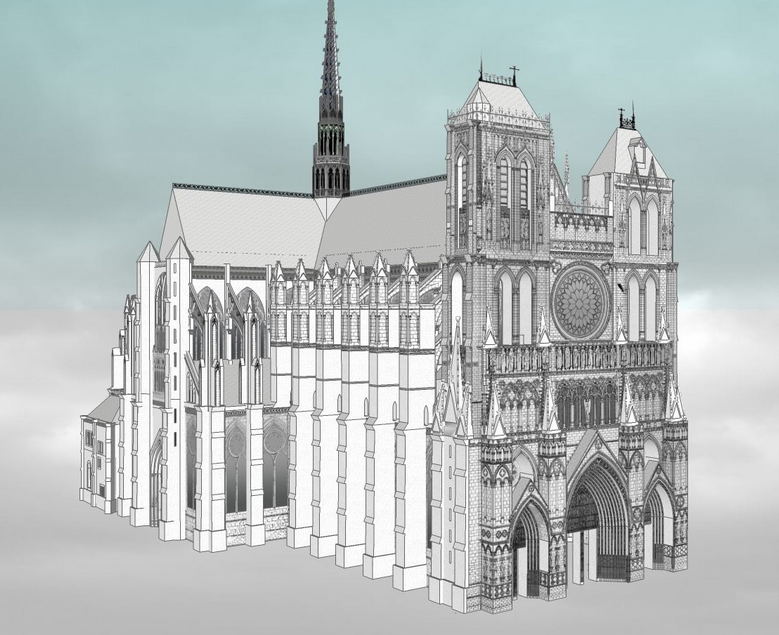

Along with the Parthenon, Amiens Cathedral is introduced each semester to students in Art Humanities. This seminar has been taught since 1947 and is required of all undergraduates as part of the Core Curriculum. Through broad introductory courses in art, literature, history, music, and science, the Core aims to produce well-rounded citizens of Columbia University students. Amiens was chosen as representative of all Gothic architecture, and as a lens through which to teach skills of visual analysis. This computer model I created instructs over 1,300 students per year.

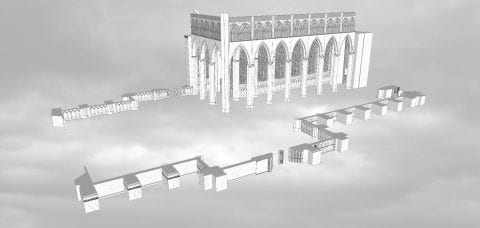

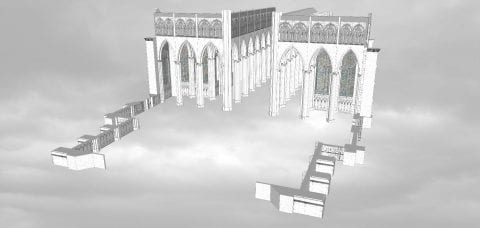

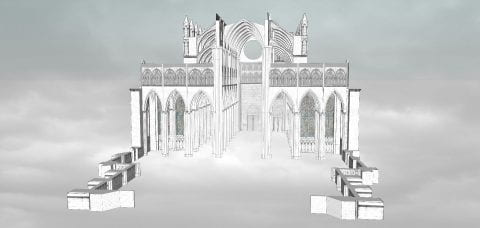

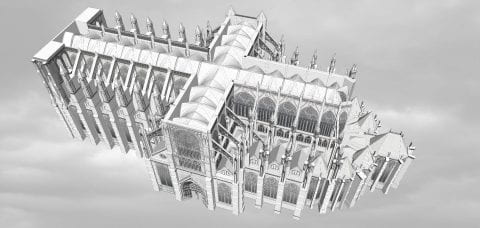

Along with the Parthenon, Amiens Cathedral is introduced each semester to students in Art Humanities. This seminar has been taught since 1947 and is required of all undergraduates as part of the Core Curriculum. Through broad introductory courses in art, literature, history, music, and science, the Core aims to produce well-rounded citizens of Columbia University students. Amiens was chosen as representative of all Gothic architecture, and as a lens through which to teach skills of visual analysis. This computer model I created instructs over 1,300 students per year. A building is experienced as a sequence of sights and sounds. A research text about such a building, however, can only capture limited information. Photography, film, and computer simulations are, in contrast, dynamic and sometimes stronger mediums to communicate the visual and engineering complexity of architecture. This project seeks to capture dynamic Amiens through a visual, auditory, and user interactive experience. Through film, one can recreate and expand the intended audience of this architecture, recreating digitally the experience of pilgrimage.

A building is experienced as a sequence of sights and sounds. A research text about such a building, however, can only capture limited information. Photography, film, and computer simulations are, in contrast, dynamic and sometimes stronger mediums to communicate the visual and engineering complexity of architecture. This project seeks to capture dynamic Amiens through a visual, auditory, and user interactive experience. Through film, one can recreate and expand the intended audience of this architecture, recreating digitally the experience of pilgrimage.