Myles Zhang

View publications by category:

200+ Posts

architecture of fear British history building construction car culture Chinatown collection data visualization Detroit dissertation project drawing Eastern State Penitentiary essay Essex County Jail film historical GIS historic preservation history of technology medieval history models Newark Newark art Newark history New York City NYC art NYC history NYC photography panopticon pastel photo-essay photography planning politics pop-up cities prison history program application essays proposals for architecture protest public speaking rail travel ruins sounds of the city time-lapse cartography walking watercolor waterfront

Tag Archives: building construction

No comments

Jersey City: Urban Planning in Historical Perspective

This project in two parts is a brief history of city planning in Jersey City

and a building-level interactive map of the entire city in 1873, 1919, and today.

.

Read / download book as PDF

Download opens in new window

.

Jersey City: Urban Planning in Historical Perspective

A booklet about the history of the master plan

Over its four-century history, the evolution of Jersey City mirrors the larger history of the New York region. Each generation of Jersey City residents and political leaders have faced different urban challenges, from affordable housing, to clean water, to air pollution, and income inequality. Each generation has responded through the tools of city planning and the master plan.

Jersey City’s six master plans – dated 1912, 1920, 1951, 1966, 1982, and 2000 – capture the city at six historical moments. Reading these plans and comparing them to each other is a lens to understand urban history, and American history more broadly.

.

Classroom Discussion Questions

1. How has the built environment of Jersey City evolved in the past century?

2. Who has the right to plan a city?

3. Who has the right to shape a city’s future?

4. Do you feel you have power over the plan of your city?

Read More

Eastern State Penitentiary Construction Sequence

“The founders of a new colony, whatever Utopia of human virtue and happiness, allot a portion of the virgin soil as a cemetery, and another portion as the site of a prison.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter, 1850

.

In 1823, Philadelphia city leaders began a unique project, to build what was allegedly the largest and most expensive building ever built in the young nation: Eastern State Penitentiary. It was to be a new kind of prison, a structure where hundreds were confined in complete and uninterrupted solitary confinement for years on end. As we reflect on Philadelphia as birthplace of American Democracy, “City of Brotherly Love,” city of the American Revolution, the architecture of Eastern State Penitentiary reminds us: Forced labor and confinement are as old as the American nation state.

This time-lapse animation with audio narration uses the tools of virtual reality to reconstruct the appearance of Eastern State Penitentiary during each year of its 148 years of operation from 1823 to 1971. This reconstruction is based on original plans and primary sources about the jail’s architecture. It uses film to reveal how the building’s envelope was expanded and modified each decade in response to evolving design philosophies, public attitudes towards incarceration, and the ever-expanding size of today’s carceral state.

.

.

Based on:

– Historic architectural plans (1837 report in French, pp. 124-38)

– Primary sources (1830 description)

– Reports on the historic preservation of this prison (1994 Historic Structures Report, Volume II)

Music by Philip Glass from the 1982 film Koyaanisqatsi, starting at minute 37:30

Link to text of audio narration

.

Computer Model

Shows prison as it appeared in the period 1836 to 1877 before later construction obstructed the original buildings.

.

Time-lapse Animation of Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

This animation reconstructs the exact conditions of the workplace, the locations of each fallen body, and the progress of the 1911 fire minute by minute. It is in an accurate-to-the-inch virtual reality model based on trial records, police reports, original measured plans, and primary sources.

.

Audio testimonies from:

Pauline Newman letter from May 1951, 6036/008, International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Archives. Cornell University, Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives.

Louis Waldman eyewitness in Labor Lawyer, New York: E.P. Dutton, 1944, pp. 32-33.

Anna Gullo in the case of The People of the State of New York v. Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, December 11, 1911, pp. 362.

.

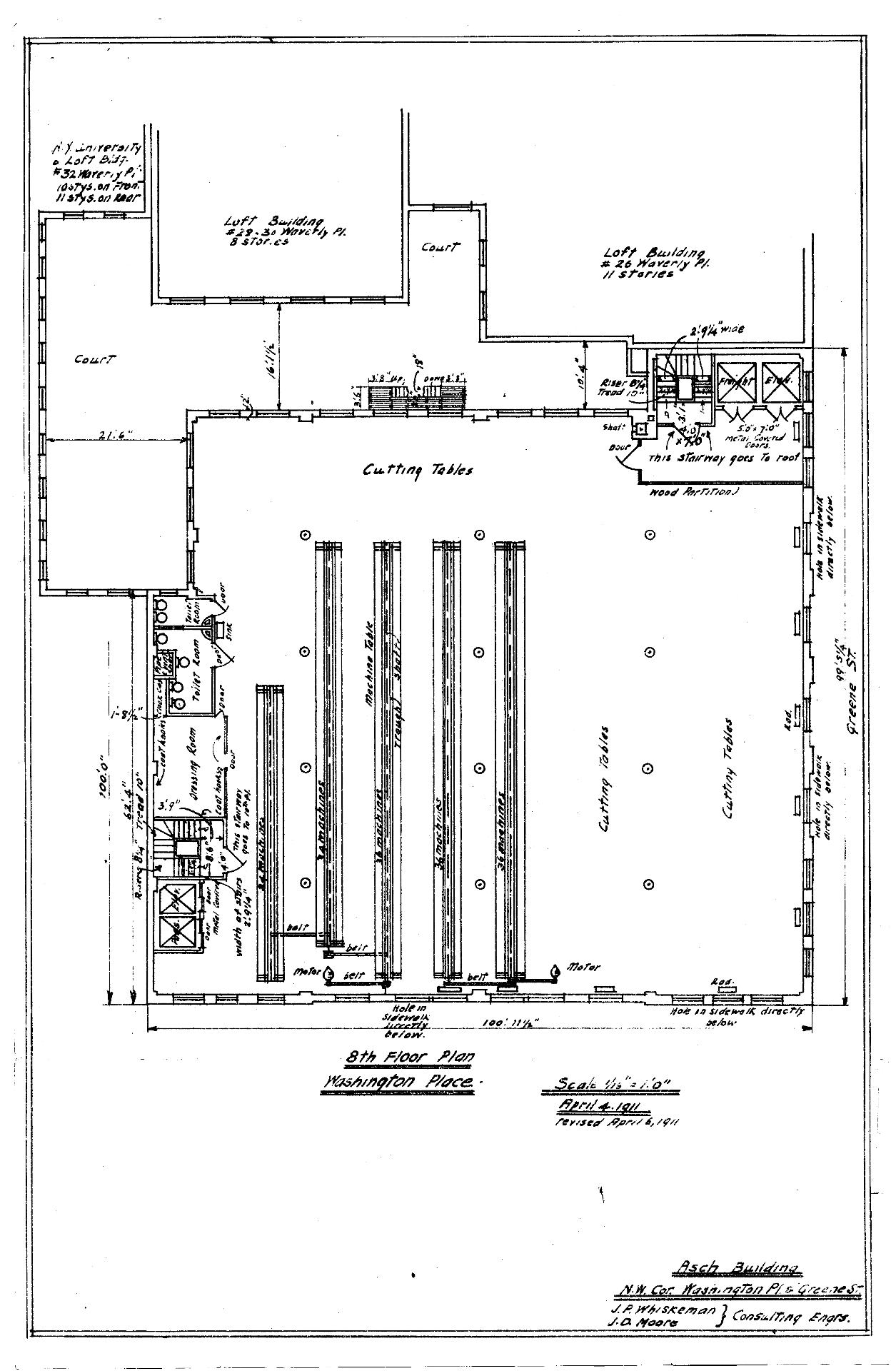

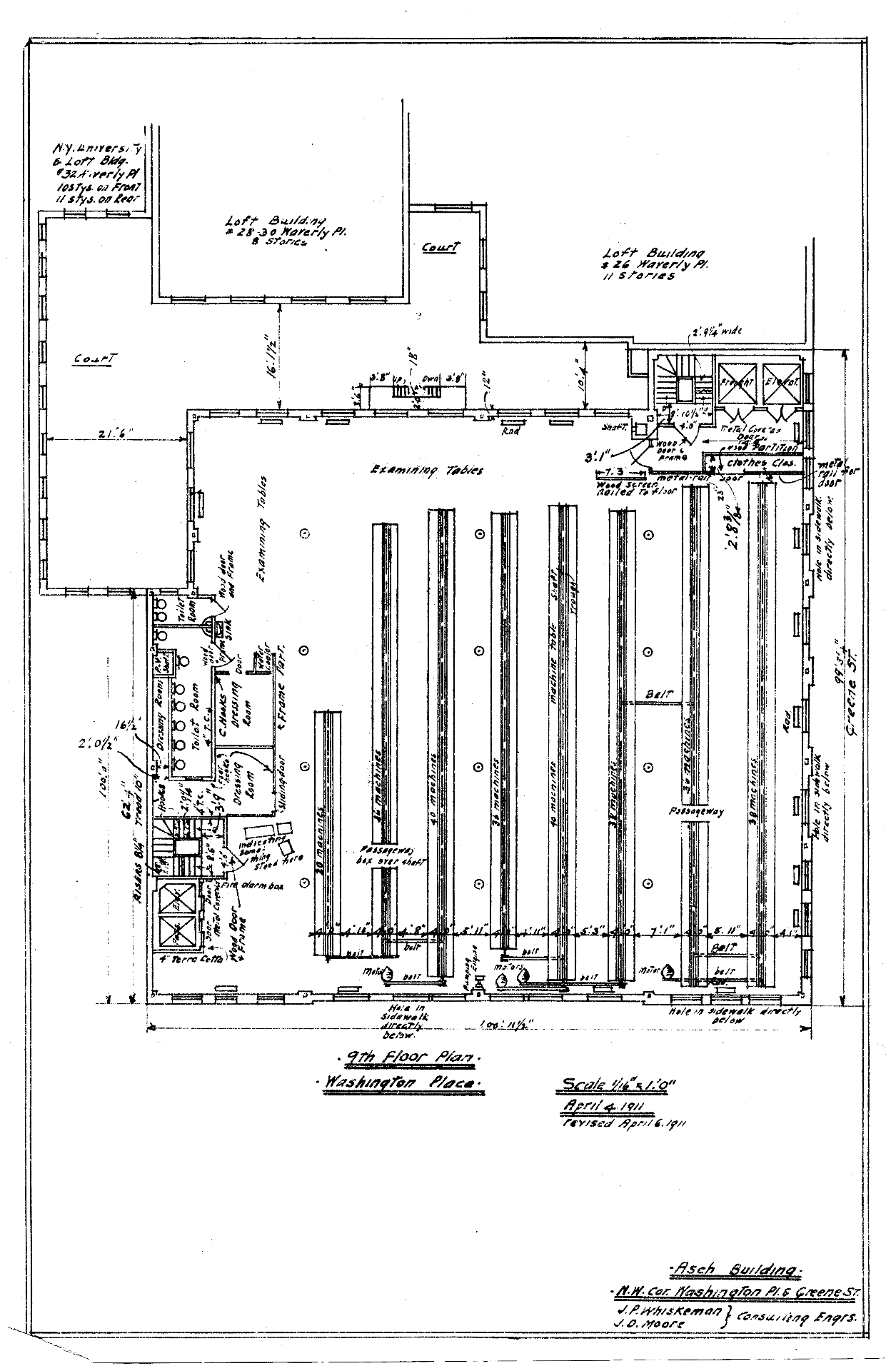

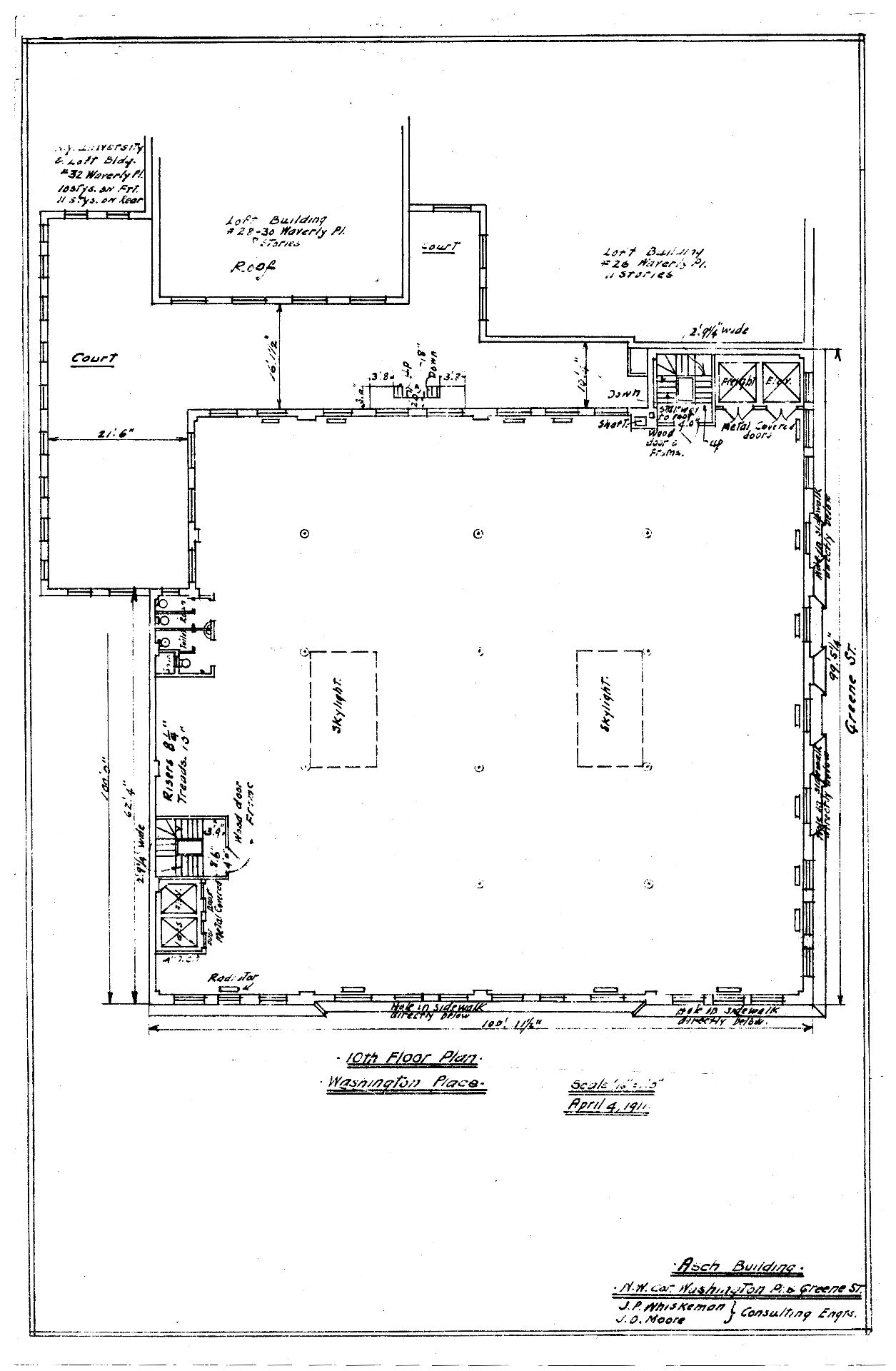

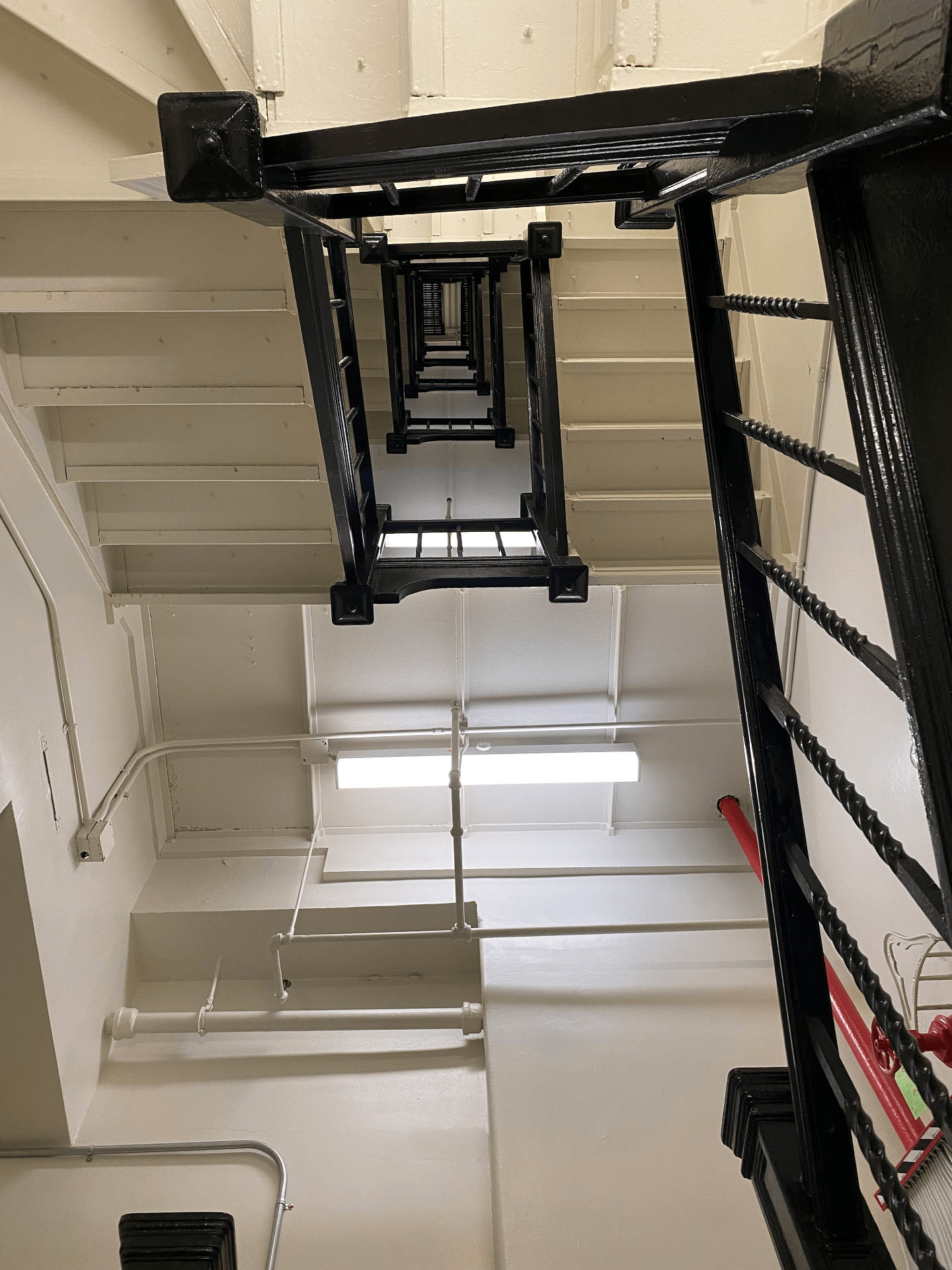

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire on Saturday, March 25, 1911 was the deadliest fire in New York City history and one of the deadliest fires in American history. The factory was located on floors eight, nine, and ten of the Asch Building, built in 1901 for various garment sweatshops in Manhattan’s West Village.

To prevent workers from taking unauthorized breaks, to reduce theft, and to block union organizers from entering the factory, the exit doors to the stairwells were locked – a common and legal practice at the time. As a result, more than half of the ninth floor workers could not escape the burning building.

As a result of the fire and lack of workplace protections, 146 garment workers – 123 women and girls and 23 men – died by fire, smoke inhalation, or jumping and falling from the 9th floor windows. Most victims were recent Italian or Jewish immigrant women and girls aged 14 to 23.

After the fire, factory owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris were not convicted and were ruled “not guilty.” They “compensated” each victim’s family a mere $75. The fire led to news laws requiring fire sprinklers in factories, safety inspections, and improved working conditions. The fire also motivated the growing International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union that organized sweatshop workers to fight for a living wage, job protections, and the right to unionize.

Click on individual annotations in model to fly around the factory and follow the time sequence of the fire.

.

Virtual Reality Model

.

Primary Sources

– Cornell University’s Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives (website)

– The 1,500 page transcript of witness and survivor testimonies (transcript)

– Victim names and causes of death (source and map of victim home addresses)

– Original architectural plans of the building used in the trial (PDF plans and source)

.

Architectural Plans

- 8th Floor

- 9th Floor

- 10th Floor

.

Audio Sources

– Horse drawn carriage

– Power loom

– Workplace bell

– Classroom

– Large crowd

– Elevator

– Small fire

– Large fire

– Fire truck bell

– Fire hose

– Dull thud

– Heartbeat

– Closing song: Solidarity Forever by Pete Seeger, 1998

– Closing song: Solidarity Forever by Twin Cities Labor Chorus, 2009

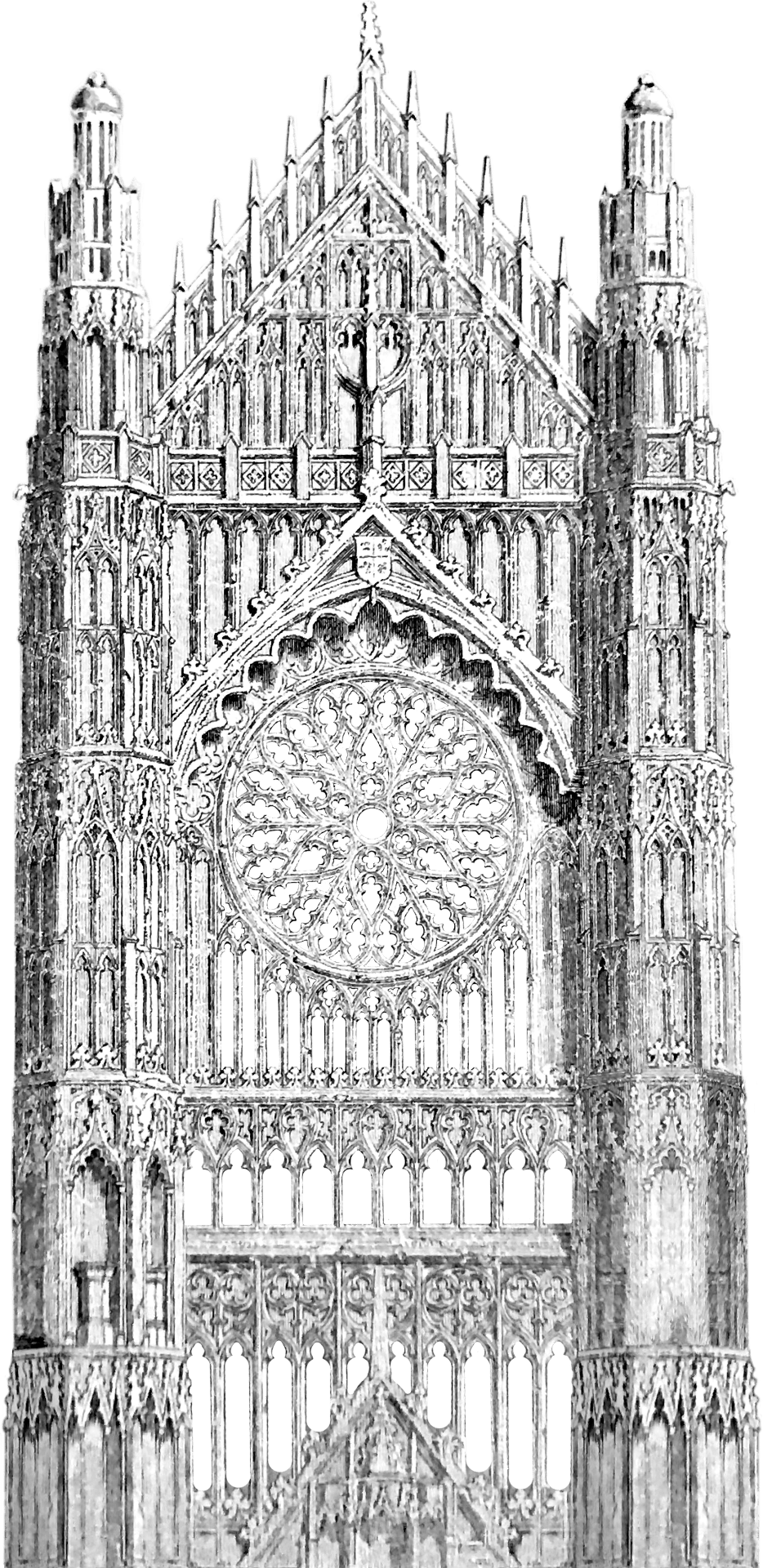

Cathedral of Beauvais: Sublime Visions; Thwarted Ambitions; A Sketch

Of all the stories of the greatest Gothic cathedrals, the tale of Beauvais is the most exciting. Construction of the Gothic cathedral began in 1225 at a time of bitter turmoil when France was establishing itself as a nation within its familiar modern geographical bounds. Beauvais, the tallest cathedral in France, was never completed, having endured two major collapses and a series of structural crises that continues to this day. Our Sketchup animation follows this dramatic narrative, allowing the viewer to experience and understand the famous collapse that brought down the upper choir in 1284 as well as the underlying design features that led to that disaster. Particularly intriguing is the visualization of the short-lived crossing tower constructed in the mid-sixteenth century and the rivalry between S-Pierre of Beauvais and Saint Peter’s in Rome.

It is hoped that besides appealing to a general audience of cathedral fans, this movie will be useful in the context of the classroom at high-school and university levels.

Directed by Stephen Murray

Produced by Myles Zhang

Special thanks to Étienne Hamon

Explore more

Further reading: Stephen Murray. Beauvais Cathedral: Architecture of Transcendence. Princeton University Press, 1989.

Visit Mapping Gothic for further photos and a panoramic tour of the cathedral interior.

Visit this link to download image stills of the cathedral at various stages of completion, for reuse in print publications.

Source files

Creating this animation required creating a computer model of the entire cathedral at all stages of construction. This model is shared below; click and drag your cursor to move around this virtual space.

Email [email protected] and [email protected] for access to source files.

High-resolution image stills from construction sequence

1220s fire to 1284 collapse

1225

1232

1240s

1240s

1250s

1250s Section

Before vs. after 1284 collapse

Before 1284 Collapse

After 1284 Collapse

After 1284 collapse vs. after 1300s rebuilding

After 1284 Collapse

After 1300s Rebuilding

1284 collapse to 1550s transept

After 1284 Collapse

1500s

1510s

1520s

1530s

1540s

Proposals for completing cathedral

1600s Proposed

1600s Proposed with Notre-Dame Type Facade

1600s Proposed with Late Gothic Facade

1600s Proposed with Late Gothic Facade

Proposed cathedral vs. actual extent of construction by 1573 collapse

1573 Proposed

1573 Actual Extent of Construction

Contemporary

Contemporary View

Contemporary View

Contemporary Section

Image sources

Hand-drawn image textures used in this model are based on actual scanned drawings of the cathedral: floorplan, choir section, choir elevation, and hemicyle section.

Audio sources

High medieval music: Viderunt Omnes by Pérotin, 1198

Late medieval music: Ave Maria by Josquin des Prez, c.1475

Contemporary cathedral: Pierre de Soleil by Philip Glass, 1986

Sound of material buckling

Sound of structural collapse

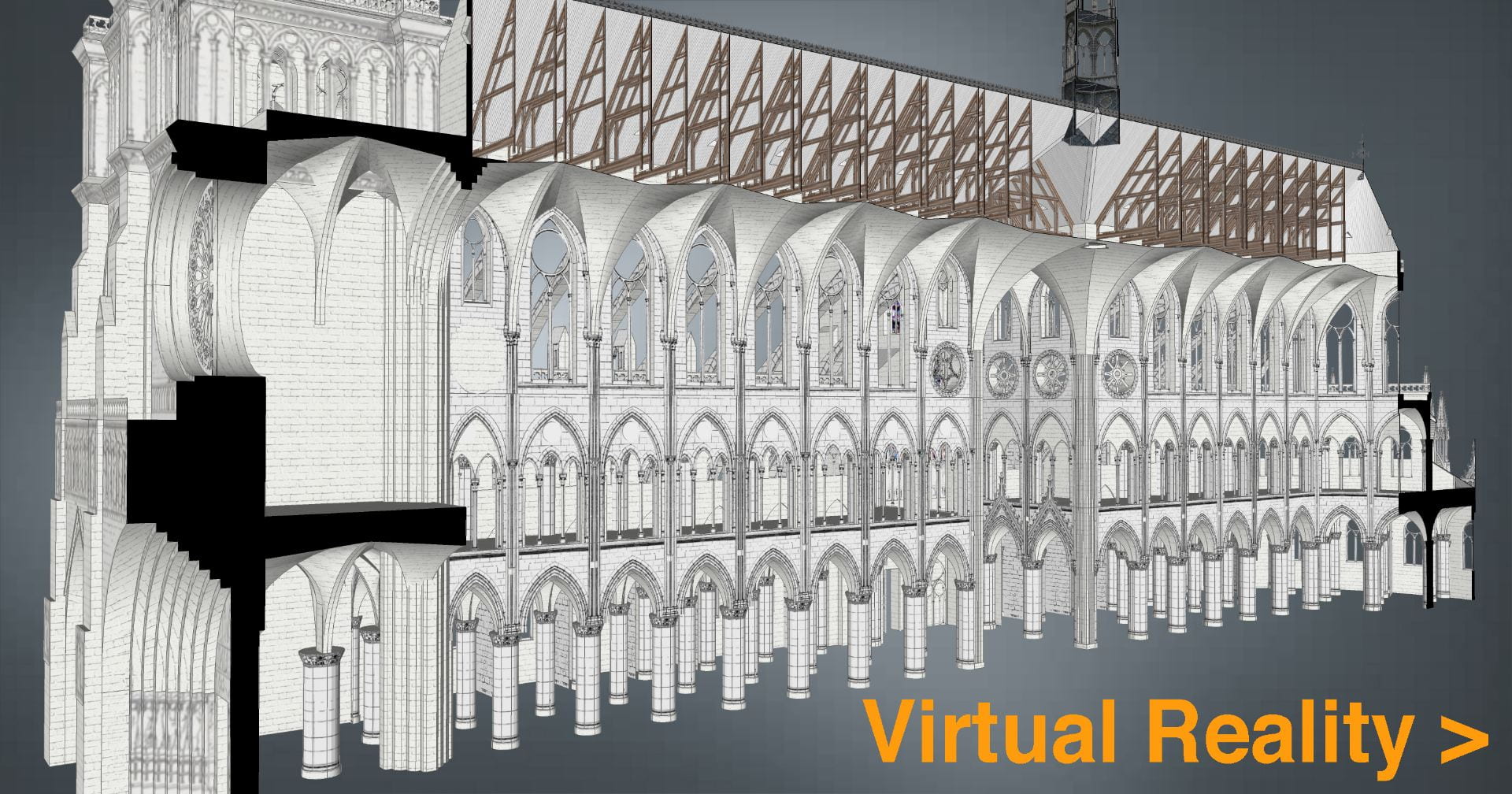

Optimizing Architectural Models for Display Online

Difficulty Level: Intermediate to Advanced

This workshop for designers is paired with an interactive history animation about the construction of Notre-Dame of Paris. You will learn how to create highly detailed but low-polygon-count models of any building you desire. These visually and geometrically complex models will have a small enough file size to load in your web browser. They can be viewed by clients, possible employers, and others online, with no need for them to download files or own specific software. Based on the content delivered in this six-part tutorial, you will be able to create similar models of any other building, real or proposed. You will be able to share these models online in a virtual reality format through Sketchfab.

1. Introduction

2. How much detail does a model need?

3. How can strategic use of components save on time and polygon count?

4. How can any image be transformed into a seamless texture?

5. How can custom image textures reduce polygon count?

6. How can models be uploaded and optimized for online views?

.

The Model:

Please allow a minute or so to load. Model is 500,000 polygons.

.

.

1. Introduction

8.5 minutes. Optimizing computer models of architecture for interaction online.

.

.

2. How much detail does a model need?

3.0 minutes. Determining the right level of detail a model needs.

.

.

3. How can strategic use of components save on time and polygon count?

6.0 minutes. Creating complex geometric forms from simple component building blocks.

.

.

4. How can any image be transformed into a seamless texture?

7.5 minutes. Creating your own seamless image textures in Photoshop.

.

.

5. How can custom image textures reduce polygon count?

7.5 minutes. Editing custom image textures to create visual complexity from geometric simplicity.

.

.

6. How can models be uploaded and optimized for online views?

4.5 minutes. Finishing touches.

.

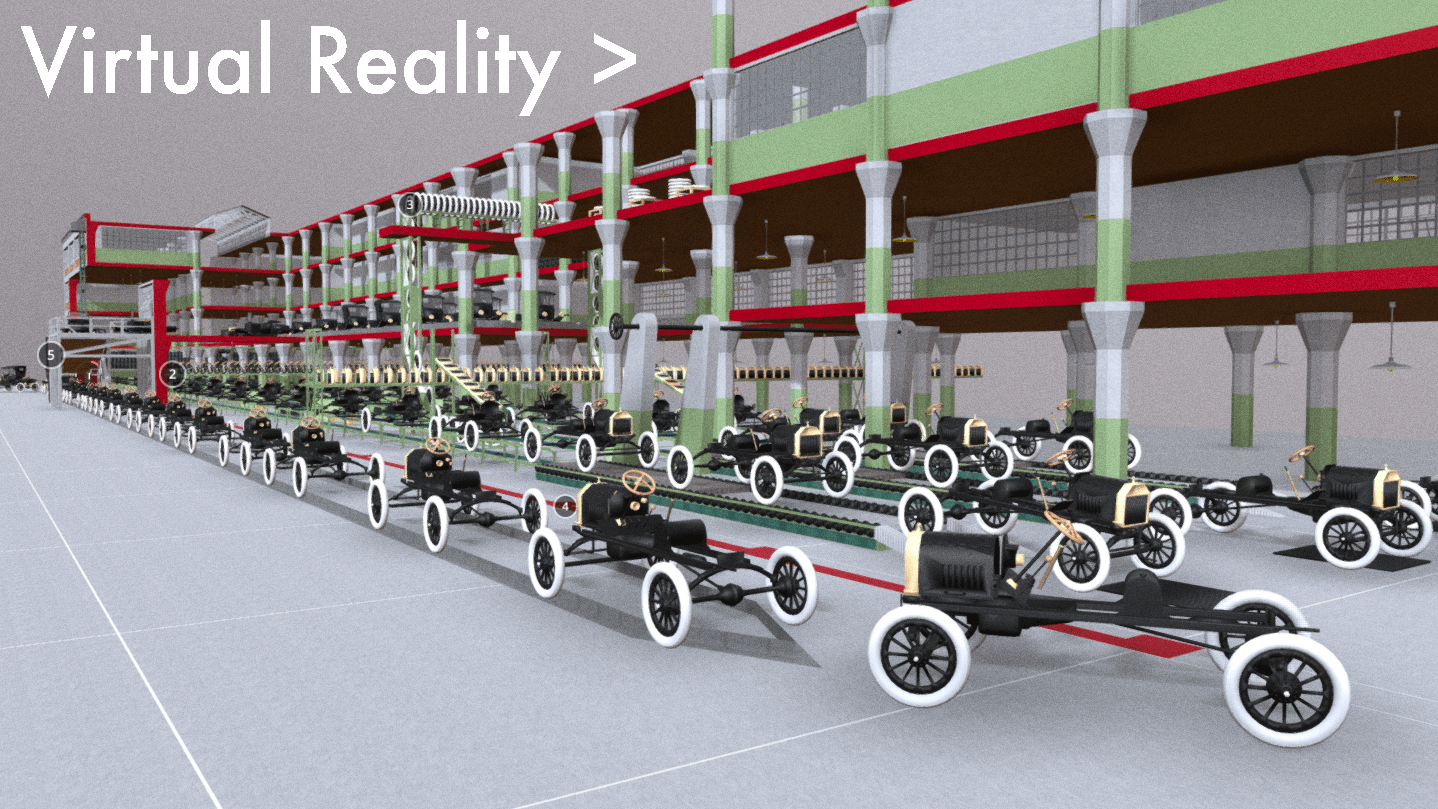

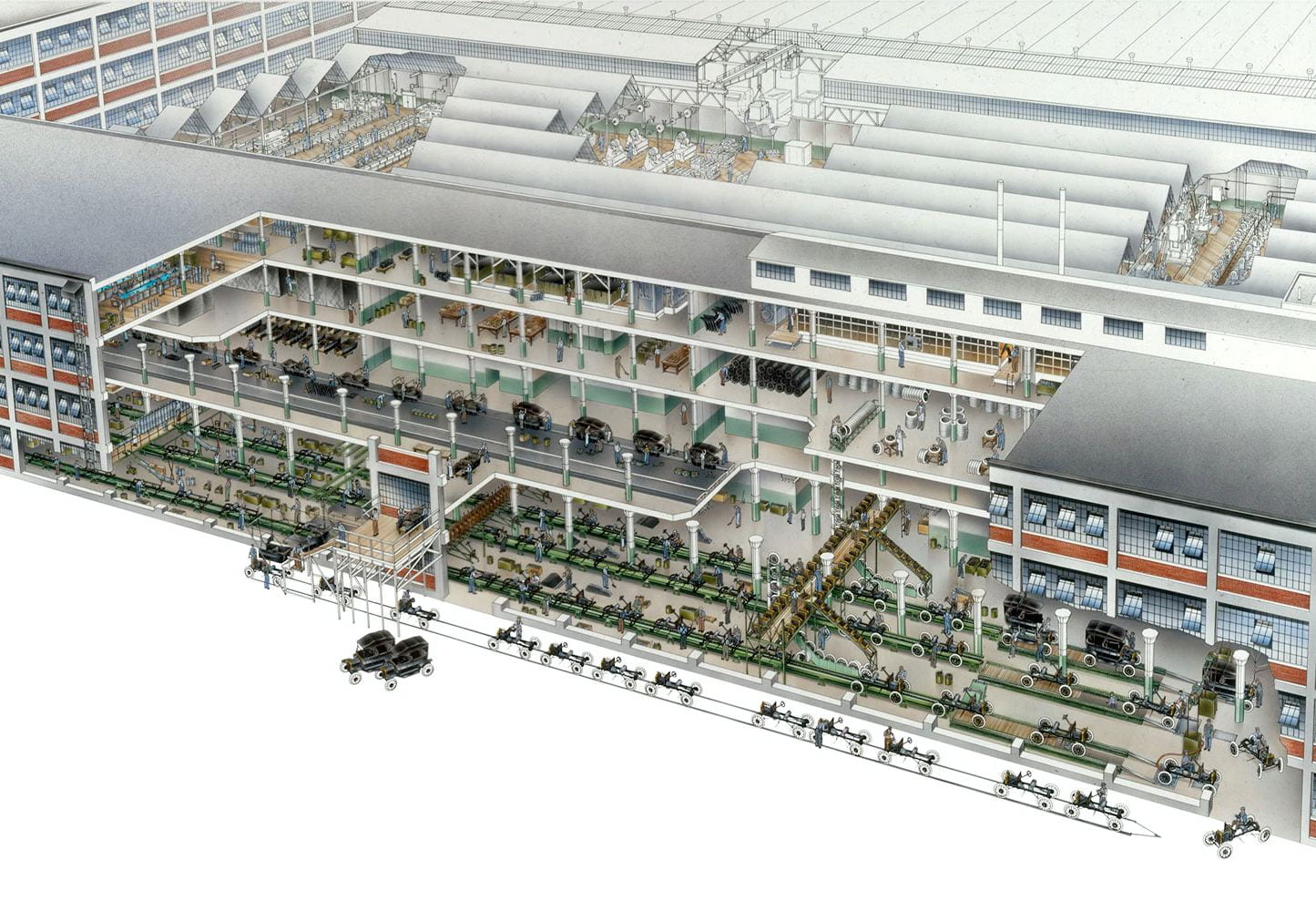

Historical Reconstruction of Ford Model T Assembly Line

As featured on Kottke.org

This digital model and film show, for the first time, the entire Model T being assembled from start to finish in a single time-lapse shot of the Ford factory in Highland Park, Michigan. Numerous photos were taken and some films were made in the 1910s and 1920s, but no film from the time tracks the entire car’s assembly from start to finish. There were many types of Model Ts produced, but the specific car shown here is the 1915 Model T Runabout. Watch the film and see as the various car components are hoisted over and bolted into place. Or walk across the factory floor in the virtual reality computer model.

.

The film’s audio replicates the sound of Model T production. The accompanying music at start and end is from the 1936 film Modern Times, where comedian Charlie Chaplin parodies Ford’s assembly line production methods.

.

Explore Model T assembly in virtual reality.

Give thirty seconds for browser to load. Link opens in new window.

.

Henry Ford did not invent the car, nor he did invent the assembly line to produce the car. For years before Ford, cars were being built in small numbers at local workshops. For centuries before Ford, assembly line production was being used to make all manner of goods like pins, fabrics, and steel. At the same time as Ford, others were making cars and building assembly lines.

Ford was not the first, but his car and moving assembly line were certainly the most successful and memorable. After creating his version of the automobile in 1896, Ford moved workshops first to Mack Avenue and later to Piquette Avenue in Detroit. These first two factories were small-scale structures for limited car production. Only in 1913 at Ford’s third factory at Highland Park did mass-production begin on a truly large scale. As shown in this film, here Ford applied assembly line methods throughout the factory to all aspects of car production.

.

Final Stage of Model T Assembly in Highland Park c.1915, David Kimble’s illustration for National Geographic

.

Between when the first Model T rolled off the assembly line in 1913 and when the fifteen millionth rolled off in 1927, the car’s appearance did not change significantly. The car chassis, motor, and color-scheme in 1927 were almost identical to 1913. Despite variations in the number of seats and exterior of car, the motor and chassis beneath were consistent and unchanging over time. Henry Ford liked it that way to bring down costs and to produce the greatest variety of car types with as few variations as possible to the car’s internal structure.

However, although Ford resisted changes to his car design, he was always redesigning the factory floor and assembly line to produce the greatest number of cars with the least amount of human labor. In this same period from 1913 to 1927, the Highland Park factory was constantly redesigned and expanded. Few records survive of all changes to the factory. However, the 1915 book Ford Methods and the Ford Shops includes detailed plans and photos of the factory at one point in time. Ford was still tinkering with the assembly line, as Model T production had begun just over a year before this book was printed. Within a few months of these photos, assembly line methods had improved once again as Ford redesigned the factory floor shown in this film. Rather than documenting Ford production for all time, this film captures Ford production the way it looked in the months it started.

.

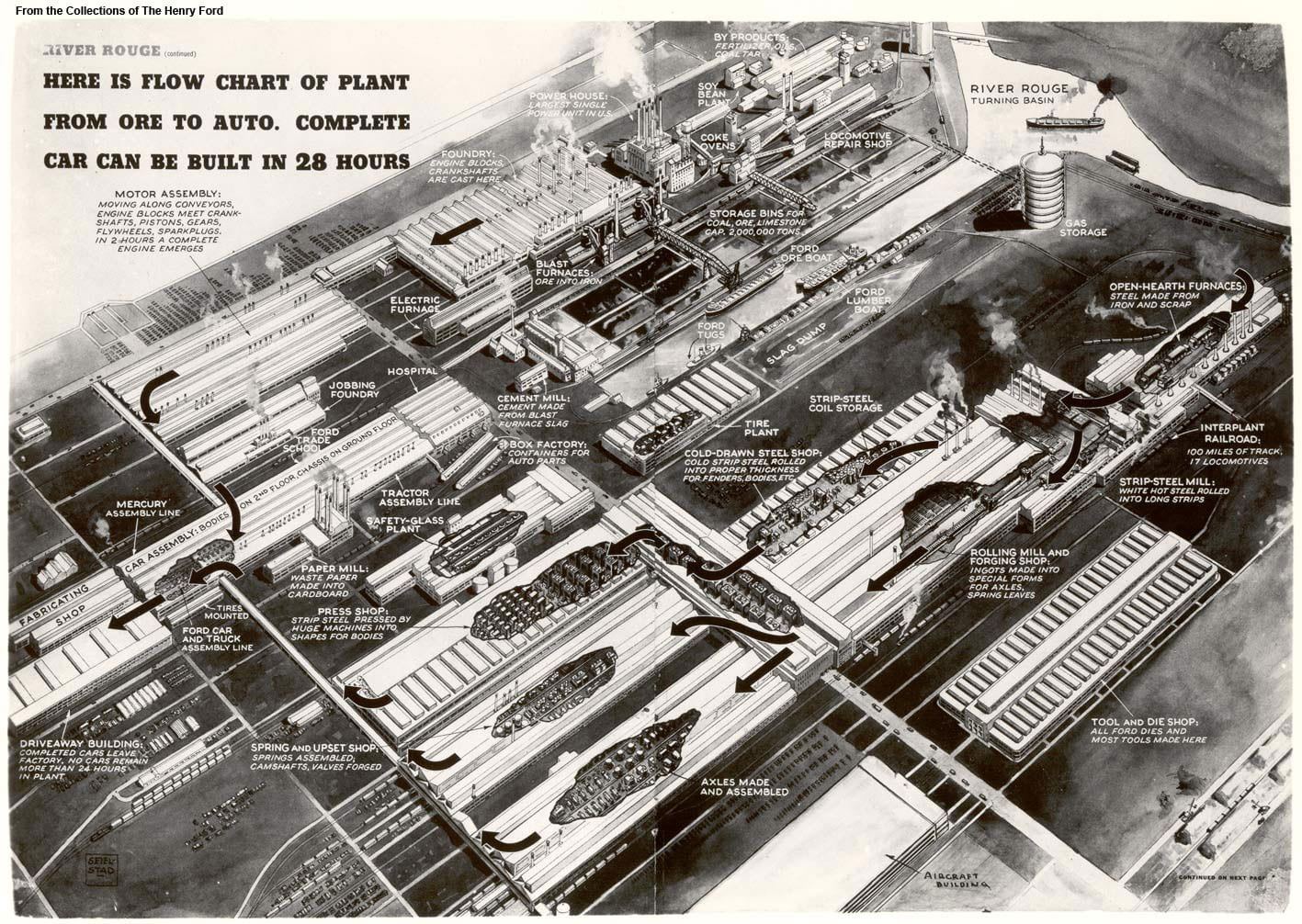

Assembly line flowchart of River Rouge c.1941, showing Ford’s production methods applied to the design of an entire complex. The ideas in embryo at Highland Park become fully visible at River Rouge.

.

After Ford stopped producing Model Ts in 1927, newer models started production at the new and larger factory at River Rouge, where Ford makes cars to this day. The Highland Park factory switched to producing other goods like tractors and later tanks for WWII. Within a few years, production methods had so quickly improved under Ford that Highland Park became too small and obsolete. The factory was largely demolished, and with its demolition the initial appearance of Ford’s first and greatest invention was lost for all time: the moving assembly line.

Some of the factory buildings still stand, and the specific part of the factory shown in this film still exists. But the buildings were all cleared of their original machinery, and the most impressive part of Ford’s invention was not the factory itself but instead the equipment and processes within that factory that are no longer visible. The buildings themselves were simply functional warehouses designed with large open spaces to allow the easy movement of machinery.

The entire complex covered many acres, and the other factories that supplied the Highland Park factory with materials and components created a web of trade that spanned the globe. Instead of filming the entire process, this film focuses on the final and most important stage of production where finished parts from all over the world and factory complex came together for final testing and assembly.

.

Sources

Main reference text: Fay Leone Faurote and Horace Lucian Arnold. Ford Methods and the Ford Shops. New York, Engineering Magazine Company: 1915. See esp. Chapter V on “Chassis-Assembling Lines” that includes factory floor plan and photos from pages 131-57. Also see pages 142-150 that describe the 45 steps required for chassis assembly. Link.

Main reference photo: David Kimble. “Exploring the Model T Factory.” Motor1.com. September 1, 2017. Link. Kimble’s image originally published in June 1987 National Geographic centerfold.

Animation opening image: Postcard of Highland Park in 1917. Link.

Animation opening music: Factory Scene from Modern Times, directed by Charlie Chaplin in 1936. Link.

Model T shown in film can be downloaded as a computer model at this link.

Notre-Dame of Paris Construction Sequence

Created with architectural historian Stephen Murray

As featured in:

- Notre Dame’s official website

- Open Culture, May 2021

- Rebuilding a Legacy, hosted April 2021 by the French Embassy, view recording

- Restoring a Gothic Masterpiece, hosted May 2021 by the Los Angeles World Affairs Council and Town Hall, view recording

- University of Michigan: College of Architecture Magazine

- Visual investigations of architecture by the French daily paper, Le Monde, December 2024, view film in English and in French

.

1. Construction time-lapse

This construction time-lapse illustrates the history of Notre-Dame from c.1060 to the present day, following ten centuries of construction and reconstruction. Model is based on actual measurements of the cathedral and was peer reviewed for accuracy by scholars at Columbia University’s art history department and at the Friends of Notre-Dame of Paris.

The film was created in the computer modeling software SketchUp, based on hand-drawn image textures. The ink drawings of nineteenth-century architect Viollet-le-Duc were scanned and applied to the model surfaces, so as to transform the two-dimensional artwork into the three-dimensional digital. I believe computer models should preserve a certain handmade quality.

.

Music: Pérotin, Viderunt Omnes

View animation with music only.

Read text of Stephen Murray’s audio narration.

.

2. Virtual reality computer model

Explore the interior and exterior of Notre-Dame in virtual reality.

Give thirty seconds for browser to load. Link opens in new window.

Complete model of Notre-Dame inside and out. Download includes simulation of cathedral construction sequence.

.

.

Fire on 15 April 2019

.

3. Research method and work flow

Learn how this model was created – and how to create similar models of your own – with my series of online tutorials shared to this page.

.

4. Computer model and construction sequence sources

– Dany Sandron and Andrew Tallon. Notre-Dame Cathedral: nine centuries of history.

– Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Drawings of Notre-Dame. From Wikimedia Commons.

– J. Clemente. Spire of Notre-Dame. From SketchUp 3D Warehouse.

– Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and Ferdinand de Guilhermy. Notre-Dame de Paris. From BnF Gallica.

– Caroline Bruzelius. “The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris” in The Art Bulletin. From JSTOR.

– Michael Davis. “Splendor and Peril: The Cathedral of Paris” in The Art Bulletin. From JSTOR.

.

5. Exterior still images from model

.

West facade

West facade towers

West facade

West facade

West facade rose window

West facade rose window

South side of nave

Buttresses on south side of nave

Buttresses on choir

Spire and western towers

Spire

Spire

South facade

South side of nave

Buttresses on hemicycle

Hemicycle

Hemicycle

South transept rose window

.

6. Interior still images

.

Nave towards choir

Clerestory windows of nave

Choir

Choir towards nave

Rafters inside roof

Rafters inside roof

South transept rose window

.

7. Dynamic angles

.

Cross Section of Transept and Choir

Cross Section

Plan of western towers

Plan of western end of nave

Plan of crossing

Plan of nave

Cross Section of South Transept

Cross Section of Transept and Nave

St. Paul’s Cathedral Dome: a synthesis of engineering and art

Developed with James Campbell, architectural historian at the University of Cambridge

Inspired by taking George Deodatis’ lectures on The Art of Structural Design

at Columbia University’s Department of Civil Engineering

.

In 1872, Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, the French author and architect celebrated for restoring Notre-Dame of Paris, wrote in his Lectures on Architecture that the form of the Gothic cathedral was the synthesis of the early Christian basilica and the Romanesque three-aisled church. In this analysis, Viollet-le-Duc reasoned that a thesis (early Christian) plus an antithesis (Romanesque) produced the synthesis (Gothic). |

. Animation from Stephen Murray |

Although the history and origins of Gothic are more complex than Viollet-le-Duc’s formula, this formula provides a method to dissect the Renaissance and Enlightenment counterpart to the medieval cathedral: the Greco-Roman basilica, as embodied by St. Paul’s Cathedral, constructed from 1675 to 1711 by Christopher Wren (1632-1723). St Paul’s is a symbol of Enlightenment-era London, built to rival its medieval counterpart of Westminster Abbey.In this essay, and in my analysis of this neoclassical cathedral, I will parallel Viollet-le-Duc’s analysis of the medieval church. The thesis is that St. Paul’s is a work of techno-scientific engineering. The antithesis is that this building is a work of art that speaks to the larger cultural moment of Enlightenment London. The synthesis is the dome of St. Paul’s that merges these two forces of engineering and art into a unified and impressive creation. |

.

Thesis: ENGINEERING

The engineering of this dome is more complex than meets the eye.

In this animated construction sequence, view how the dome was engineered.

.

Music from the organ (William Tell’s Overture) and bells of St Paul’s (recorded 2013)

.

St. Paul’s Cathedral features an innovative triple dome structure. On the circular drum, the inner dome rises and is visible from the cathedral interior. Above this inner dome, a brick cone rises to support the 850 ton lantern. This brick cone also supports the wood rafters and frame of the outer dome, which is covered in wood and lead. This three dome system allows the cathedral to support such a heavy lantern, all the while maintaining the great height needed to be a visible London landmark.

- Inner dome – visible from inside and purely for show; height 225 ft (69m)

- Middle brick cone – a brick cone that is invisible from below but supports the 850 ton lantern above; height 278 ft (85m)

- Outer dome – a wood and lead-roofed structure visible from the cathedral exterior; height 278 ft (85m)

- Lantern – an 850 ton stone lantern and cross, whose weight is carried to the ground via the middle brick cone 365ft (111m)

The inner and outer domes are decorative, while the brick cone is the true weight-bearing support. The model below is created from measured plans and is accurate to reality.

Read More

.

Virtual Reality Model

(click to play)

.

Computer Model of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon

Created at the University of Cambridge: Department of Architecture

As part of my Master’s thesis in Architecture and Urban Studies, as featured by:

– Special Collections department at University College London

– Open Culture

– Tomorrow City

– Aeon: a world of ideas

.

To say all in one word, it [the panopticon] will be found applicable, I think, without exception, to all establishments whatsoever, in which, within a space not too large to be covered or commanded by buildings, a number of persons are meant to be kept under inspection.

– Jeremy Bentham

.

.

Since the 1790s, Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon remains an influential building and representation of power relations. Yet no structure was ever built to the exact dimensions Bentham indicates in his panopticon letters. Seeking to translate Bentham into the digital age, I followed his directions and descriptions to construct an exact model in virtual reality. What would this building have looked like if it were built? Would it have been as all-seeing and all-powerful as Bentham claims?

Explore Bentham’s panopticon in the animation above or in virtual reality below

based on Bentham’s drawings at University College London:

.

.

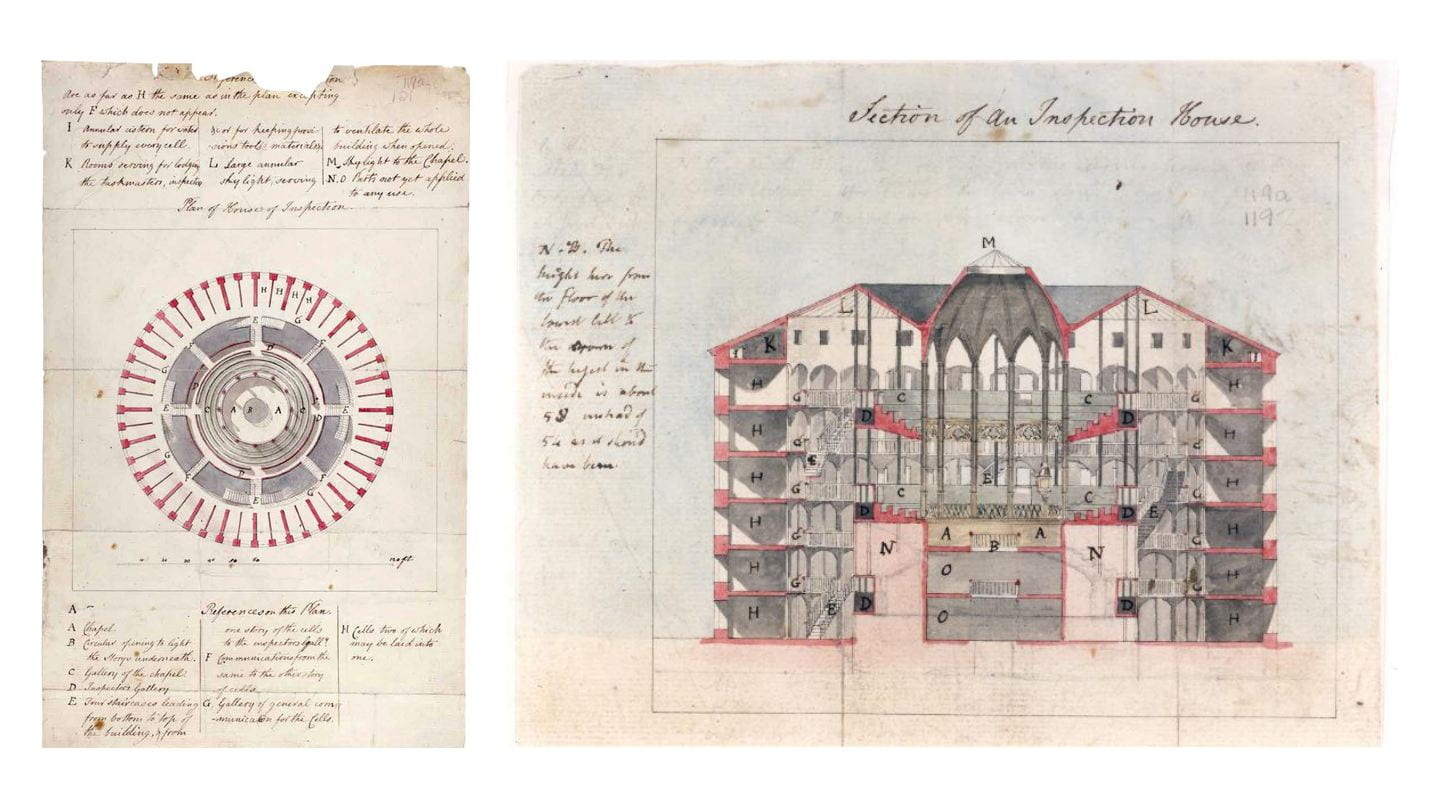

c.1791 plans of panopticon, drawn by architect Willey Reveley for Jeremy Bentham

Creative Commons image credit: Bentham MS Box 119a 121, UCL Special Collections

.

Panopticon: Theory vs. Reality

Central to Bentham’s proposed building was a hierarchy of: (1) the principal guard and his family; (2) the assisting superintendents; and (3) the hundreds of inmates. The hierarchy between them mapped onto the building’s design. The panopticon thus became a spatial and visual representation of the prison’s power relations. As architectural historian Robin Evans describes: “Thus a hierarchy of three stages was designed for, a secular simile of God, angels and man.”

.

Spatial diagram of power relations

Obstructed view from ground floor

Author’s images from computer model

.

To his credit, Bentham recognized that an inspector on the ground floor could not see all inmates on the upper floors. The angle of view was too steep and obstructed by stairs and walkways. To this end, Bentham proposed that a covered inspection gallery be erected between every two floors of cells.

By proposing these three inspection galleries, Bentham addressed the problem of inspecting all inmates. However, he created a new problem: From no central point was it now be possible to see all activity, as the floor plans below show. The panoramic view below shows the superintendent’s actual field of view, from which he could see into no more than four complete cells at a time. The view from the center was not, in fact, all-seeing. Guards would have to walk a continuous circuit round-and-round, as if on a treadmill. They, too, are prisoners to the architecture.

.

Panopticon panorama from guard’s point of view

Section showing each guard’s cone of vision

.

Guard’s cone of vision

Guard’s walking circuit

Author’s images from computer model

.

The intervening stairwells and inspection corridors between the perimeter cells and the central tower might have allowed inspectors to see into the cells. Yet these same architectural features would also have impeded the inmates’ view toward the central rotunda. Bentham claimed this rotunda could become a chapel, and that inmates could hear the sermon and view the religious ceremonies without ever needing to leave their cells. The blinds, normally closed, could be opened up for viewing the chapel.

.

Rotunda with blinds closed

Rotunda with blinds opened

.

Bentham’s suggestion was problematic. The two cross sections above show that, although some of the inmates could see the chapel from their cells, most would be unable to do so.

In spite of all these obvious faults in panopticon design, Bentham still claimed that all inmates and activities were visible and controlled from a single central point. When the superintendent or visitor arrives, no sooner is he announced that “the whole scene opens instantaneously to his view,” Bentham wrote.

.

.

Despite Bentham’s claims to have invented a perfect and all-powerful building, the real panopticon would have been flawed were it built as this data visualization helps illustrate. Although the circular form with central tower was chosen to facilitate easier surveillance, the realities and details of this design illustrate that constant surveillance was not possible. That the British public and Parliament rejected Bentham’s twenty year effort to build a real panopticon should be no surprise.

However flawed the architecture, Bentham remained ahead of his time. He envisioned an idealistic and rational, even utopian, surveillance society. Without the necessary (digital) technology to create this society, Bentham fell back on architecture to make this society possible. The failure of this architecture and its obvious shortcomings do not invalidate Bentham’s project. Instead, these flaws with architecture indicate that Bentham envisioned an institution and society that would only become possible through new technologies invented hundreds of years later.

.

Related Projects

My computer model is available here in virtual reality.

Read my research on Eastern State Penitentiary, a radial prison descended from Bentham’s panopticon

.

.

Credits

Supervised by Max Sternberg at Cambridge, advised by Philip Schofield at UCL

The archives and publications of UCL special collections, Bentham MS Box 119a 121

Audio narration by Tamsin Morton

Audio credits from Freesound

– panopticon interior ambiance

– panopticon exterior ambiance

– prison door closing

– low-pitched bell sound

– high-pitched bell sound