Based on primary sources and archival records of the slave trade

Written for Rebecca Scott’s history seminar: The Law in Slavery and Freedom

Read / download essay as PDF, opens in new tab

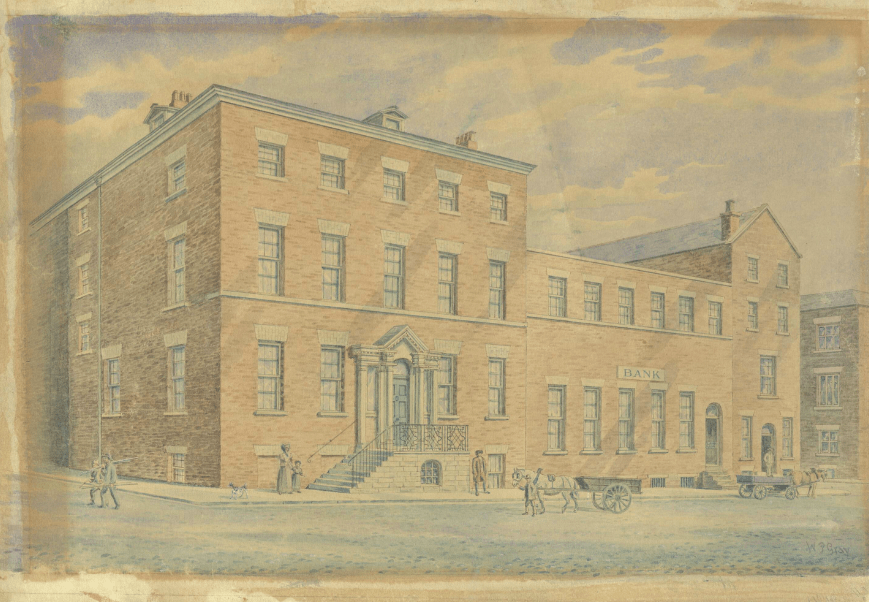

Selling slaves equipped Liverpool merchant Thomas Leyland with the money to create what is now the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank of China. With profits from merchant trading and Caribbean slave sales, Leyland wrote thousands of letters to build a Transatlantic business. Analyzing these 250-year-old business records reveals the mechanisms of human trafficking.

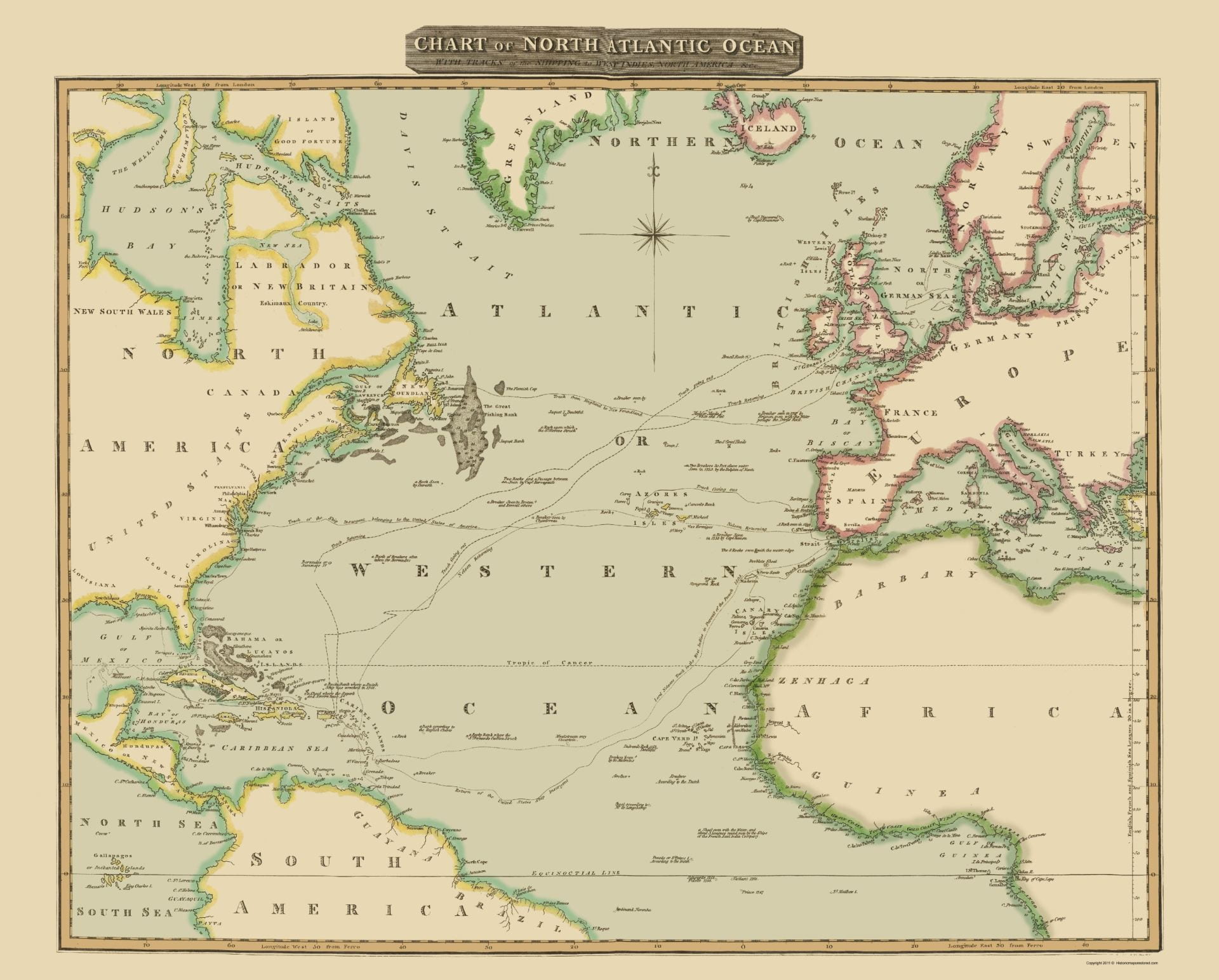

From the comfortable distance of Liverpool, Bristol, and London, Leyland’s letters describe bodies he and his co-investors would never see some 4,500 miles away in the Caribbean. In an age before telegraphs, steamships, and rapid transcontinental communication, Leyland required a paper trail to carry out his orders. Across the distant branches of his global business empire, the medium of written letters linked these distant investments to London.

Thomas Leyland was a banker, trader, millionaire, and three times Mayor of Liverpool. Born 1752 to working class family of limited means, little land, and no royal titles, he chanced upon wealth when in 1776 he won £20,000 in the lottery. He was only twenty-four. This wealth he first invested in merchant ships to sell consumer goods and transport the likes of oats, peas, wheat, oatmeal, bacon, hogs, and lard from Irish farmers to British markets.[1] By 1783, with profits from these businesses, Leyland turned to the risk-intensive capital required to launch slave voyages, purchasing captives on the West African coast and selling them to cotton and sugar plantations in the Caribbean. His ~70 recorded slaving voyages transported an estimated 22,365 captives to the Americas, of whom about one in ten died during the months-long voyage. By his death in 1827, Leyland had amassed a fortune of some £600,000.[2]

Examination of his account books in Liverpool and at the University of Michigan show the 1789-90 journey of the Hannah with 294 African captives and the 1792-92 journey of the Jenny with 250 captives. Both year-long journeys began in Liverpool, sailed for West Africa, exchanged guns and cloth for human cargo, sold their captives in Jamaica, and then sailed home to Britain. His written correspondence of 2,262 letters also survives in the Liverpool Record Offices. Close reading of these documents in parallel – the ship manifest and the letter book – unpacks the mechanics and finances of Leyland’s slaving operation turned modern bank.

These documents reveal the mechanisms and mentality of a human trafficker. Never in them does Leyland claim – as a moral cover for their profit motives – that such African bodies were being saved from a darker fate of certain death from their African captors. These letters never claimed either that slavery was justified. Nor did Leyland use the cover of Christianity and the Christian language of missionary work to justify in his letters what he did to these Africans. His few written comments on the subject do not even recognize the need to justify slavery, the slave trade, or his role in it.[3]

Instead, the letters present the trafficking of human cargo in matter-of-fact language. In one day’s correspondence and from the same desk, Leyland ordered his agents to landscape the lawn of his country house, purchase grain from Ireland, deliver rum to an associate, and sell Africans in Jamaica. The tone of Leyland’s writing in flowing cursive script and flowery prose does not change, whether discussing matters as banal as drapery or as life changing as human trafficking. From Liverpool, Leyland managed business but at no point had he ever seen or inspected the human products he was buying, and nor did his London colleagues. In this way, these letters all describe slaves in the abstract, as bodies, as cargo, and profits per head sold. Leyland’s writing transforms the human body – a name, a person, a fate – into nothing more than a number on a page.

Watercolor of Leyland & Bullins bank on York Street in Liverpool in 1807. Bank offices at right. Leyland’s family home at left. Warehouse for Caribbean rum, Irish oats, and slave trade goods in rear. This building survives today unchanged. [4].

Read More