Myles Zhang

View publications by category:

200+ Posts

architecture of fear British history building construction car culture Chinatown collection data visualization Detroit dissertation project drawing Eastern State Penitentiary essay Essex County Jail film historical GIS historic preservation history of technology medieval history models Newark Newark art Newark history New York City NYC art NYC history NYC photography panopticon pastel photo-essay photography planning politics pop-up cities prison history program application essays proposals for architecture protest public speaking rail travel ruins sounds of the city time-lapse cartography walking watercolor waterfront

Tag Archives: architecture of fear

No comments

Architecture of Redemption?

Contradictions of Solitary Confinement

at Eastern State Penitentiary

Master’s thesis at the University of Cambridge: Department of Art History & Architecture

Developed with Max Sternberg, historian at Cambridge

.

View of cellblocks and guard tower

Eastern State Penitentiary guard tower

.

The perfect disciplinary apparatus would make it possible for a single gaze to see everything constantly. A central point would be both the source of light illuminating everything, and a locus of convergence for everything that must be known: a perfect eye that nothing would escape and a centre towards which all gazes would be turned.

– Michel Foucault

.

Abstract

In the contemporary imagination of prison, solitary confinement evokes images of neglect, torture, and loneliness, likely to culminate in insanity. However, the practice originated in the late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century as an enlightened approach and architectural mechanism for extracting feelings of redemption from convicts.

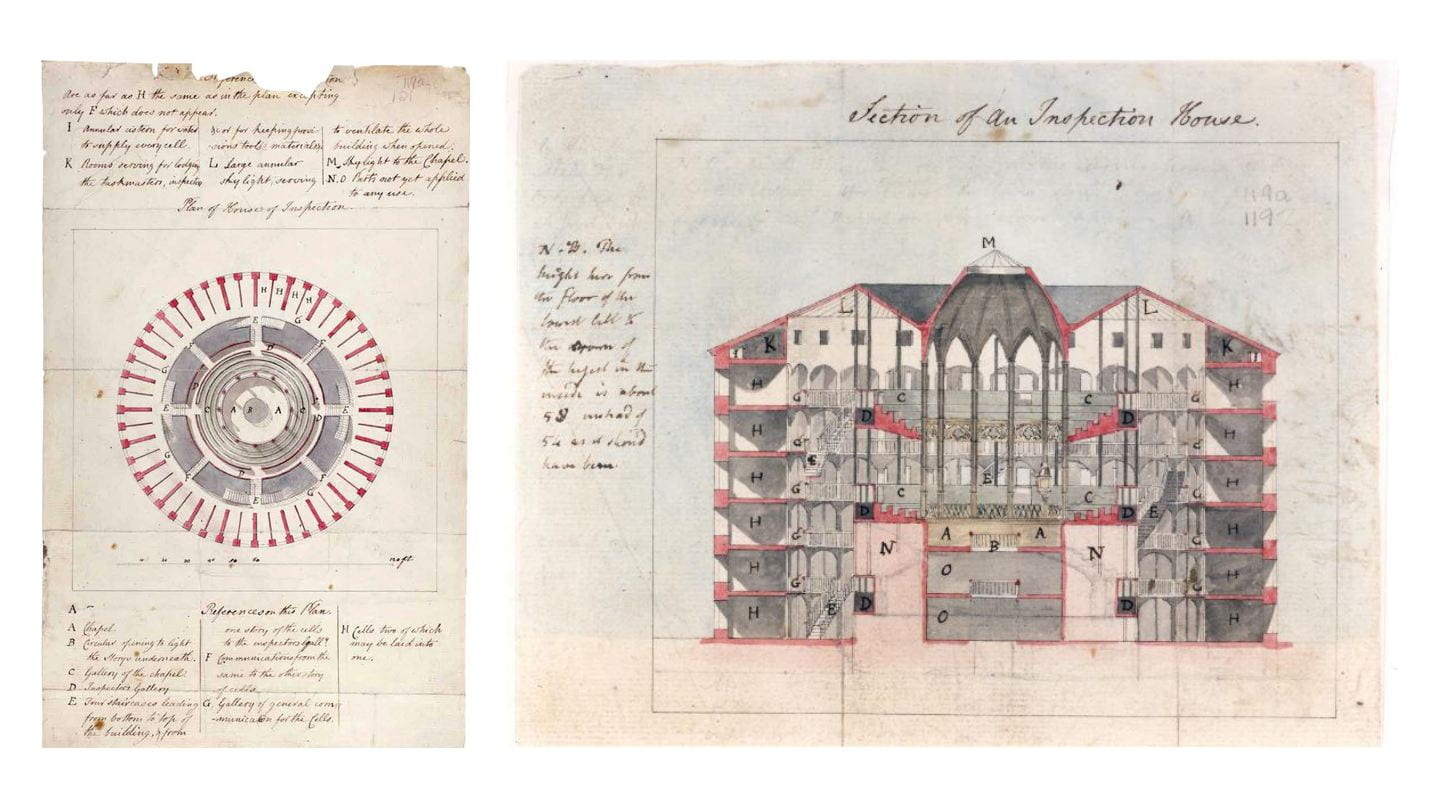

This research examines the design of Eastern State Penitentiary, built by English-born architect John Haviland from 1821 to 1829 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This case study explores the builders’ challenge of finding an architectural form suitable to the operations and moral ambitions of solitary confinement. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, Haviland’s design inspired the design of over 300 prisons worldwide. With reference to primary sources and to philosophers Jeremy Bentham and Michel Foucault, this research interrogates the problematic assumptions about architecture and human nature encoded in the form of solitary confinement practiced at Eastern State Penitentiary, which has wider implications for the study of surveillance architecture.

.

Click here to read

Click here to read

.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Max Sternberg for his attentive guidance throughout this research, and his support of my experience in providing undergraduate supervisions at Cambridge. I am grateful to Nick Simcik Arese for encouraging me to examine architecture as the product of labor relations and relationships between form and function. I am inspired by Alan Short’s lectures on architecture that criticize the beliefs in health and miasma theory. My research also benefits from co-course director Ronita Bardhan. Finally, this research is only possible through the superb digitized sources created by the staff of Philadelphia’s various archives and libraries.

I am particularly indebted to the guidance and friendship of Andrew E. Clark throughout my life.

The COVID-19 pandemic put me in a “solitary confinement state-of-mind,” allowing me to research prison architecture from a comfortable confinement of my own.

.

Related Projects

.

Digital Reconstruction

|

Digital Reconstruction

|

Exhibit on Prison Design

|

.

Tour of desolate NYC during Coronavirus

This NYC tour follows the route of Kenneth T. Jackson’s night tour. As a Columbia University undergraduate, I joined Jackson’s 2016 night tour of NYC by bike, from Harlem, down the spine of Manhattan, and over the bridge to Brooklyn.

With a heavy heart, I gathered my courage on 30 March 2020 to revisit my beloved NYC, along this same route in the now sleeping city attacked by an invisible pathogen. The empty streets hit me with emotions in the misty and rainy weather – perhaps fitting for the city’s low morale.

.

.

The tour route is drawn below. View this drawing in detail.

.

.

Audio effects from Freesound: Street ambiance, highway ambiance, passing car, siren blast, short siren, long siren

Eastern State Penitentiary: Decorative Fortress

Developed with Max Sternberg, historian at the University of Cambridge

.

Presentation

Paper delivered 6 March 2020 at the University of Cambridge: Department of Architecture

As part of my Master’s thesis in Architecture and Urban Studies

.

.

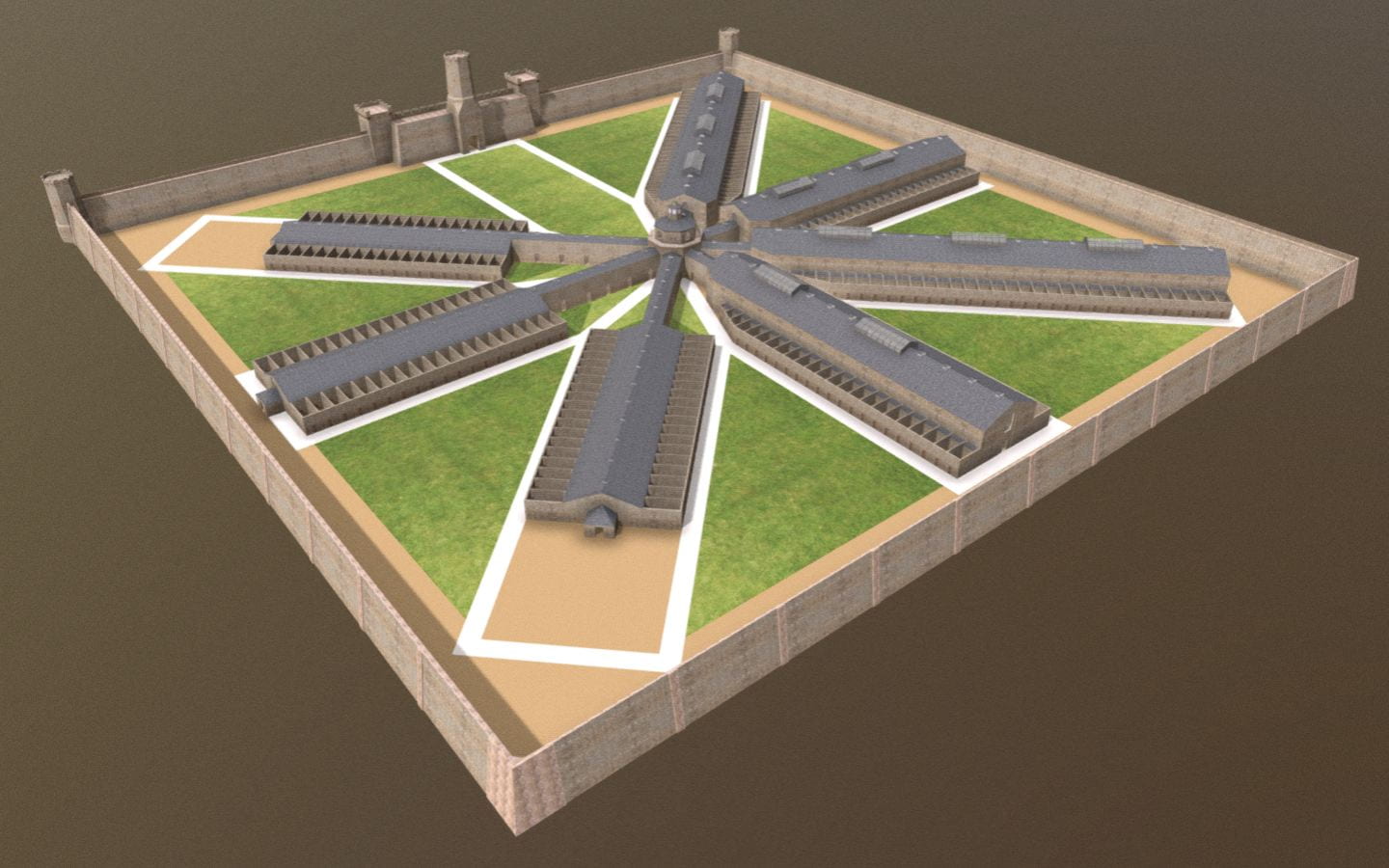

Digital Reconstruction

Created in SketchUp. Based on original drawings and plans of the prison.

All measurements are accurate to reality.

.

With ambient music from Freesound

.

Eastern State Penitentiary was completed in 1829 in northwest Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by architect John Haviland. It was reported as the most expensive and largest structure yet built in America.

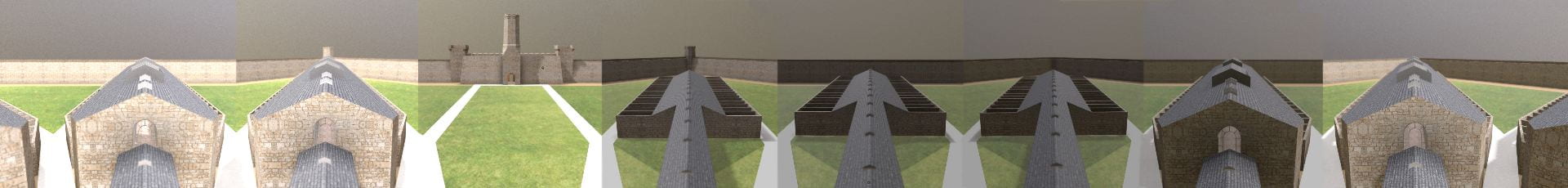

The design featured a central guard tower from which seven cell blocks radiated like a star. This system allowed a single guard to survey all prisoners in one sweep of the eye. A square perimeter wall surrounded the entire complex – thirty feet high and twelve feet thick. The decorative entrance resembled a medieval castle, to strike fear of prison into those passing. This castle contained the prison administration, hospital, and warden’s apartment.

As we approach the central tower, we see two kinds of cells. The first three cell blocks were one story. The last four cell blocks were two stories. Here we see the view from the guard tower, over the cell block roofs and over the exercise yards between cell blocks. Each cell had running water, heating, and space for the prisoner to work. Several hundred prisoners lived in absolute solitary confinement. A vaulted and cathedral-like corridor ran down the middle of each cell block. The cells on either side were stacked one above the other. Cells on the lower floor had individual exercise yards, for use one hour per day. John Haviland was inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon. (Don’t know what the panopticon is? Click here for my explanation.)

Over its century in use, thousands visited and admired this design. An estimated 300 prisons around the world follow this model – making Eastern State the most influential prison ever designed.

.

360° panoramic view from guard tower

.

Computer Model

Shows prison as it appeared in the period 1836 to 1877 before later construction obstructed the original buildings.

.

.

Research Paper

Eastern State Penitentiary’s exterior resembles a medieval castle. More than a random choice, the qualities of Gothic attempt to reflect, or fall short of reflecting, the practices of detention and isolation within. Contrary to the claim often made about this structure that the appearance was supposed to strike fear into passerby, the use of Gothic is in many ways unexpected because of its untoward associations with darkness and torture, which the prison’s founders were working to abolish. It is therefore surprising that America’s largest and most modern prison should evoke the cruelties and injustices of the medieval period. The choice of Gothic appearance, and the vast funds expended on the external appearance few inmates would have seen, leads one to question the audience of viewers this penitentiary was intended for – the inmates within or the public at large?

This essay responds by analyzing what the Gothic style represented to the founders. The architectural evocation of cruelty and oppression was, in fact, not contradictory with the builders’ progressive intentions of reforming and educating inmates. This prison’s appearance complicates our understanding of confinement’s purpose in society. The two audiences of convicted inmates and tourist visitors would have received and experienced this prison differently, thereby arriving at alternative, even divergent, understandings of what this prison meant. More than an analysis of the architect John Haviland and of the building’s formal qualities in isolation, this essay situates this prison in the larger context of Philadelphia’s built environment.

.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to my supervisor Max Sternberg, to my baby bulldog, and to my ever-loving parents for criticizing and guiding this paper.

.

Continue reading paper.

Opens in new window as PDF file.

.

Three-dimensional floor plan

Floor plan showing extent of vision from central guard tower

View of cellblocks and guard tower

View from northeast

View from southeast

View from guard tower

Individual exercise yards

Cross section cell block 4

.

Related Projects

– Master’s thesis on this prison

– Animation of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon

– Computer model of panopticon in virtual reality

– Lecture on problems with the panopticon

What’s wrong with Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon?

Animation and research as featured by Open Culture

.

Postmodernist thinkers, like Michel Foucault, interpret Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, invented c.1790, as a symbol for surveillance and the modern surveillance state.

This lecture is in two parts. I present a computer model of the panopticon, built according to Bentham’s instructions. I then identify design problems with the panopticon and with the symbolism people often give it.

.

Related Projects

– Computer animation of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon

– View the panopticon in virtual reality

– Explore about Eastern State Penitentiary, a building inspired by Bentham

Computer Model of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon

Created at the University of Cambridge: Department of Architecture

As part of my Master’s thesis in Architecture and Urban Studies, as featured by:

– Special Collections department at University College London

– Open Culture

– Tomorrow City

– Aeon: a world of ideas

.

To say all in one word, it [the panopticon] will be found applicable, I think, without exception, to all establishments whatsoever, in which, within a space not too large to be covered or commanded by buildings, a number of persons are meant to be kept under inspection.

– Jeremy Bentham

.

.

Since the 1790s, Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon remains an influential building and representation of power relations. Yet no structure was ever built to the exact dimensions Bentham indicates in his panopticon letters. Seeking to translate Bentham into the digital age, I followed his directions and descriptions to construct an exact model in virtual reality. What would this building have looked like if it were built? Would it have been as all-seeing and all-powerful as Bentham claims?

Explore Bentham’s panopticon in the animation above or in virtual reality below

based on Bentham’s drawings at University College London:

.

.

c.1791 plans of panopticon, drawn by architect Willey Reveley for Jeremy Bentham

Creative Commons image credit: Bentham MS Box 119a 121, UCL Special Collections

.

Panopticon: Theory vs. Reality

Central to Bentham’s proposed building was a hierarchy of: (1) the principal guard and his family; (2) the assisting superintendents; and (3) the hundreds of inmates. The hierarchy between them mapped onto the building’s design. The panopticon thus became a spatial and visual representation of the prison’s power relations. As architectural historian Robin Evans describes: “Thus a hierarchy of three stages was designed for, a secular simile of God, angels and man.”

.

Spatial diagram of power relations

Obstructed view from ground floor

Author’s images from computer model

.

To his credit, Bentham recognized that an inspector on the ground floor could not see all inmates on the upper floors. The angle of view was too steep and obstructed by stairs and walkways. To this end, Bentham proposed that a covered inspection gallery be erected between every two floors of cells.

By proposing these three inspection galleries, Bentham addressed the problem of inspecting all inmates. However, he created a new problem: From no central point was it now be possible to see all activity, as the floor plans below show. The panoramic view below shows the superintendent’s actual field of view, from which he could see into no more than four complete cells at a time. The view from the center was not, in fact, all-seeing. Guards would have to walk a continuous circuit round-and-round, as if on a treadmill. They, too, are prisoners to the architecture.

.

Panopticon panorama from guard’s point of view

Section showing each guard’s cone of vision

.

Guard’s cone of vision

Guard’s walking circuit

Author’s images from computer model

.

The intervening stairwells and inspection corridors between the perimeter cells and the central tower might have allowed inspectors to see into the cells. Yet these same architectural features would also have impeded the inmates’ view toward the central rotunda. Bentham claimed this rotunda could become a chapel, and that inmates could hear the sermon and view the religious ceremonies without ever needing to leave their cells. The blinds, normally closed, could be opened up for viewing the chapel.

.

Rotunda with blinds closed

Rotunda with blinds opened

.

Bentham’s suggestion was problematic. The two cross sections above show that, although some of the inmates could see the chapel from their cells, most would be unable to do so.

In spite of all these obvious faults in panopticon design, Bentham still claimed that all inmates and activities were visible and controlled from a single central point. When the superintendent or visitor arrives, no sooner is he announced that “the whole scene opens instantaneously to his view,” Bentham wrote.

.

.

Despite Bentham’s claims to have invented a perfect and all-powerful building, the real panopticon would have been flawed were it built as this data visualization helps illustrate. Although the circular form with central tower was chosen to facilitate easier surveillance, the realities and details of this design illustrate that constant surveillance was not possible. That the British public and Parliament rejected Bentham’s twenty year effort to build a real panopticon should be no surprise.

However flawed the architecture, Bentham remained ahead of his time. He envisioned an idealistic and rational, even utopian, surveillance society. Without the necessary (digital) technology to create this society, Bentham fell back on architecture to make this society possible. The failure of this architecture and its obvious shortcomings do not invalidate Bentham’s project. Instead, these flaws with architecture indicate that Bentham envisioned an institution and society that would only become possible through new technologies invented hundreds of years later.

.

Related Projects

My computer model is available here in virtual reality.

Read my research on Eastern State Penitentiary, a radial prison descended from Bentham’s panopticon

.

.

Credits

Supervised by Max Sternberg at Cambridge, advised by Philip Schofield at UCL

The archives and publications of UCL special collections, Bentham MS Box 119a 121

Audio narration by Tamsin Morton

Audio credits from Freesound

– panopticon interior ambiance

– panopticon exterior ambiance

– prison door closing

– low-pitched bell sound

– high-pitched bell sound

You may reuse content and images from this article, according to the Creative Commons license.

Exhibition Design for the Old Essex County Jail

Developed in collaboration with Newark Landmarks

and the master’s program in historic preservation at Columbia University

.

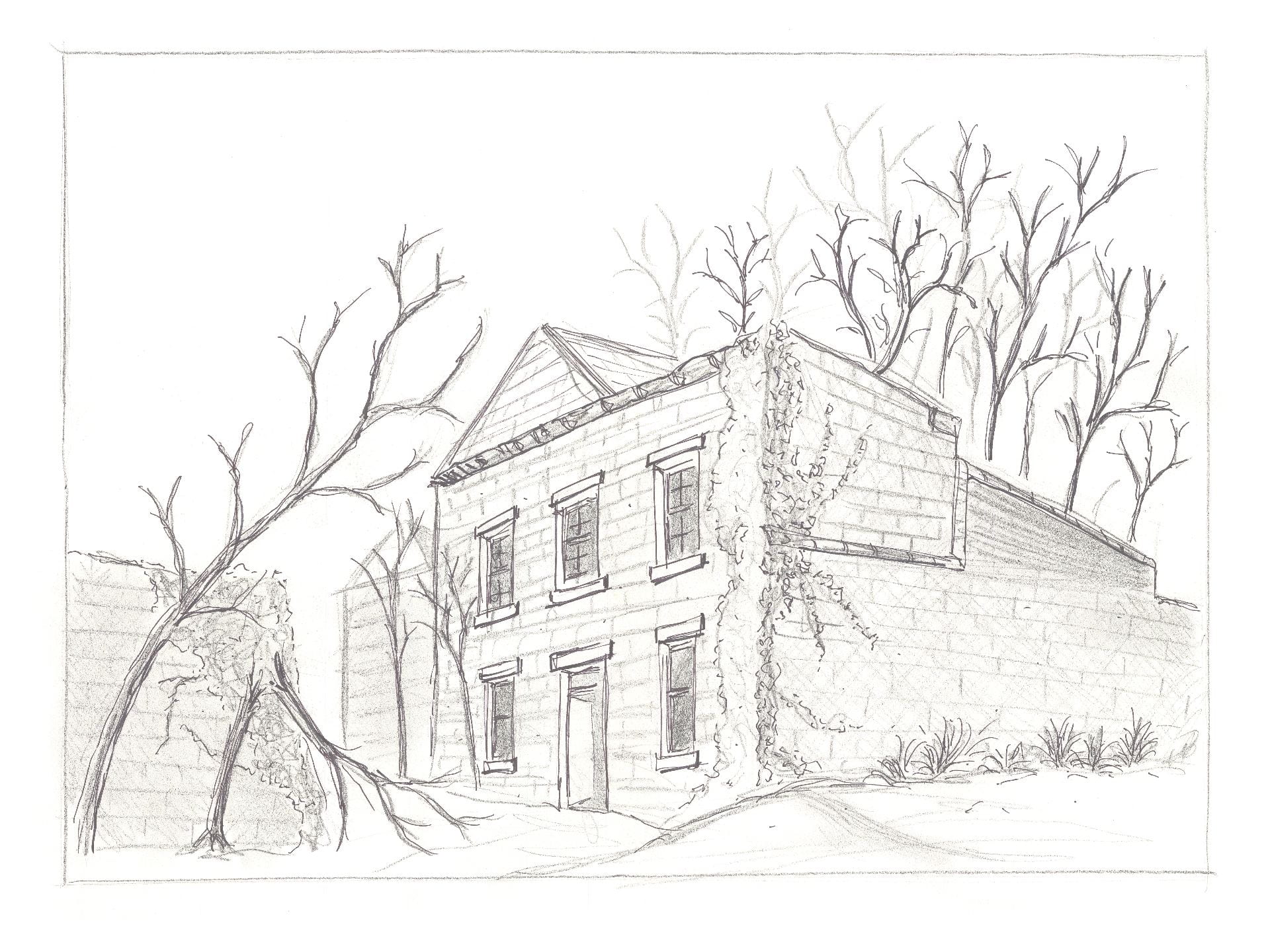

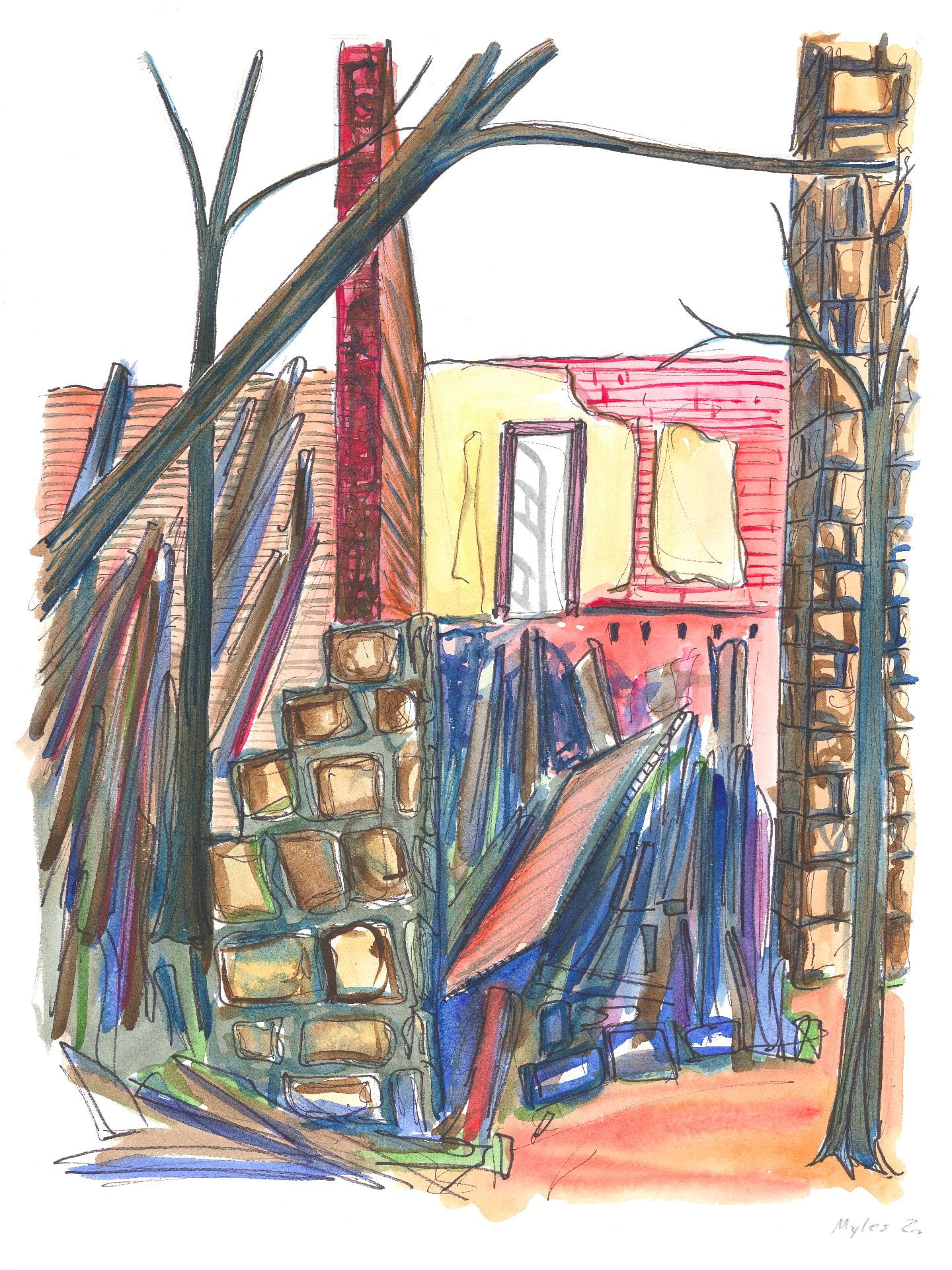

Warden’s House c.1967

Warden’s House in 2019

Jail entrance gate

.

Since 1971, the old Essex County Jail has sat abandoned and decaying in Newark’s University Heights neighborhood. Expanded in stages since 1837, this jail is among the oldest government structures in Newark and is on the National Register of Historic Places. The building needs investment and a vision for transforming decay into a symbol of urban regeneration. As a youth in Newark, I explored and painted this jail, and therefore feel a personal investment in the history of this place. Few structures in this city reflect the history of racial segregation, immigration, and demographic change as well as this jail.

In spring 2018, a graduate studio at Columbia University’s master’s in historic preservation program documented this structure. Eleven students and two architects recorded the jail’s condition, context, and history. Each student developed a reuse proposal for a museum, public park, housing, or prisoner re-entry and education center. By proposing eleven alternatives, the project transformed a narrative of confinement into a story of regeneration.

Inspired by this academic project and seeking to share it with a larger audience, I and Zemin Zhang proposed to transform the results of this studio into a larger dialogue about the purpose of incarceration. With $15,000 funding from Newark Landmarks, I translated Columbia’s work into an exhibition. I am grateful to Anne Englot and Liz Del Tufo for their help securing space and funding. Over spring 2019, I collaborated with Ellen Quinn and a team at New Jersey City University to design the exhibit panels and to create the corresponding texts and graphics. The opening was held in May 2019, and is recorded here.

.

.

My curator work required translating an academic project into an exhibit with language, graphics, and content accessible to the public. Columbia examined the jail’s architecture and produced numerous measured drawings of the site, but they did not examine social history. As the curator, I shifted the exhibit’s focus from architecture to the jail’s social history – to use the jail as a tool through which to examine Newark’s history of incarceration. As a result, much of my work required supplementing Columbia’s content with additional primary sources – newspaper clippings, prison records, and an oral history project – that tell the human story behind these bars. I worked with local journalist Guy Sterling to interview former jail guards and Newark Mayor Ras Baraka about his father’s experience incarcerated here during the 1967 civil unrest. The exhibit allowed viewers to hear first-hand accounts of prison life and to view what the Essex County Jail looked like in its heyday from the 1920s to 1960s. Rutgers-Newark organized seminars connected to the jail exhibit on the topic of incarceration in America, and what practical steps can be taken to change the effects of the growth of incarceration.

The finished exhibit was on display from May 15 through September 27, 2019. The exhibit makes the case for preserving the buildings and integrating them into the redevelopment of the surrounding area. The hope is that, by presenting this jail’s history in a public space where several thousand people viewed it per week, historians can build support for the jail’s reuse. Over the next year, an architecture studio at the New Jersey Institute of Technology’s College of Architecture and Design is conducting further site studies. Before any work begins, the next immediate step is to remove all debris, trim destructive foliage, and secure the site from trespassers. These actions will buy time while the city government and the other stakeholders determine the logistics of a full-scale redevelopment effort.

My interest in prisons drew me to this project. This jail’s architect was John Haviland, who was a disciple of prison reformers John Howard and Jeremy Bentham. In my MPhil thesis research about Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary, I developed my exhibit research by looking at the social and historical context of John Haviland and early prisons. As I describe, Eastern State began as a semi-utopian project in the 1830s but devolved by the 1960s into a tool of control social and a symbol of urban unrest.

.

Launch Virtual Exhibit Website

.

Myles Zhang

.

Related content

-

Read my January 2021 article in The Newarker magazine.

-

Read this July 2020 article from Jersey Digs

about my exhibit and the New Jersey Institute of Technology’s proposal to reuse this jail site. -

Hear my September 2019 interview about this jail and exhibit from Pod & Market.

-

Explore this jail as an interactive exhibit online.

-

View this artwork as part of my short film from 2016 called Pictures of Newark.

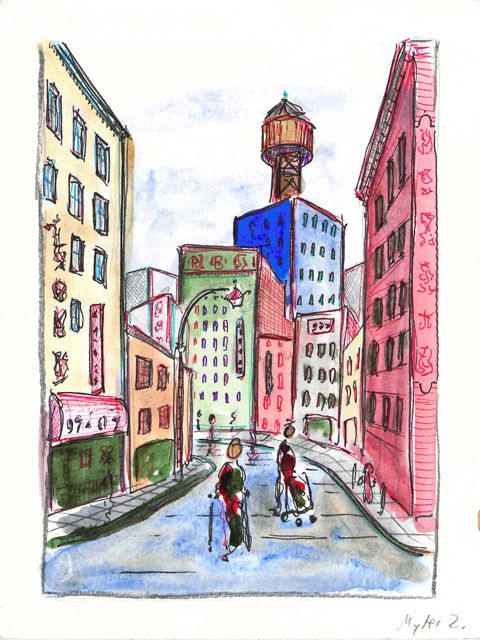

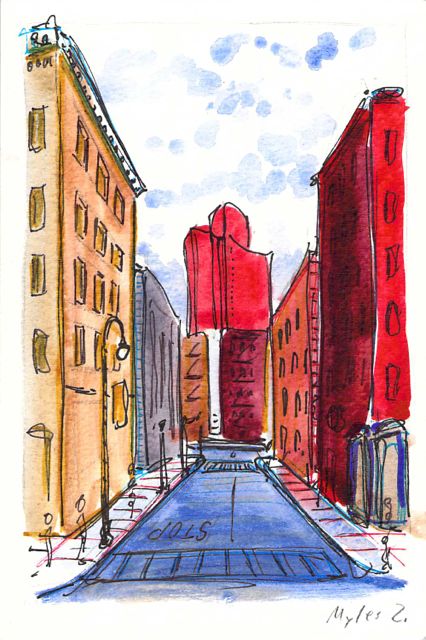

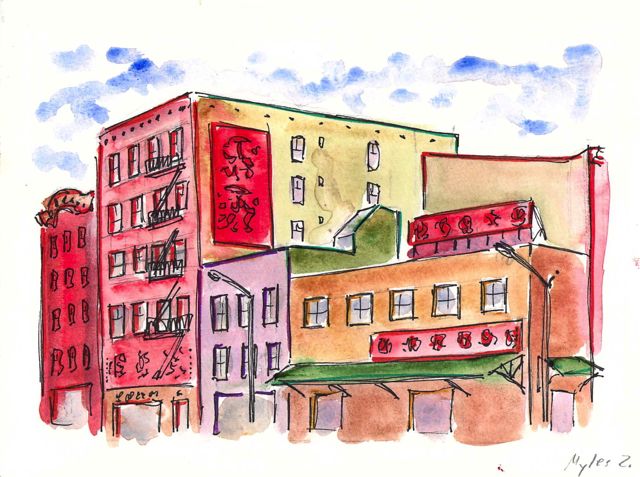

Architecture of Exclusion in Manhattan Chinatown

Originally published in the 2018-19 edition of the Asia Pacific Affairs Council journal with help from Seeun Yim at Columbia University’s Weatherhead East Asian Institute, pages 18-20

.

Canal and Mott Street

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act restricted Chinese immigration to the US, prohibited Chinese females from immigrating on grounds of “prostitution,” and revoked the citizenship of any US citizen who married a Chinese male. The consequences of this xenophobic legislation motivated Chinese immigrants to flee racial violence in the American West and to settle in Manhattan’s Chinatown. With a population now of around fifty thousand (2010 census), this remains the largest ethnically Chinese enclave in the Western Hemisphere.

Barbershop Row on Doyers Street

Thanks to New York’s geographic location as a port city with high industrial employment and easy connections to the American interior, this city became the primary point of entry for waves of immigrant groups in the nineteenth century: Irish, Germans, Italians, and Eastern Europeans. What makes the Chinese different, though, is the survival and resilience of the immigrant community they created. Other immigrant groups – namely the Germans and Irish – converged around large neighborhoods and surrounded themselves with familiar languages and businesses. Of these enclaves, all have since disappeared. The children of these first-generation immigrants successfully assimilated into American society, earned higher incomes than their parents, and therefore chose to disperse to non-immigrant neighborhoods with better housing stock and schools. Yet, the Chinese remained.

The resilience of this community results from a confluence of factors: cultural, geographic, and political. Of innumerable immigrant groups to the US, the Chinese were among the only to have the most restrictive laws placed on their immigration. This stigma drove them toward three types of low-paid labor – with which white Americans still deeply associate with the Chinese – laundries, restaurants, and garment manufacturing. Like the Chinese, other groups – particularly Irish-immigrant females – began working in these professions, but they soon climbed the social ladder.

Mosco Street and Mulberry Bend

As an architectural historian, I see that the political and racial agenda of exclusion is imprinted in the built environment of Chinatown. To present this neighborhood’s geography: For most of its history, Chinatown was bordered to the north by Canal Street, to the east by Bowery, and to the South and West by the city’s federal courthouse and jail. The center of this community lies on the low wetland above a filled-in and polluted lake called the Collect Pond. Historically, this area contained the city’s worst housing stock, was home to the city’s first tenement building (65 Mott Street), and was the epicenter for waterborne cholera during the epidemics of 1832 (~3,000 deaths) and again in 1866 (1,137 deaths). The city’s first slum clearance project was also in Chinatown to create what is now present-day Columbus Park.

Race-based policies of exclusion can take different forms in the built-environment. The quality of street cleaning and the frequency of street closures are a place to start. Some of the city’s dirtiest sidewalks and streets are consistently located within Chinatown – as well as some of the most crowded with street vendors, particularly Mulberry and Mott Street). Yet, as these streets continue northward above Canal Street, their character changes. The street sections immediately north in the enclave of Little Italy are frequently cleaned and closed for traffic most of the year to create a car-free pedestrian mall bordered by upscale Italian restaurants for tourists. The sections of Mulberry Street in Chinatown are always open to traffic and truck deliveries.

Grocery Store at Bayard and Mulberry Streets

Unequal treatment continues when examining the proximity of Chinatown to centers of political power and criminal justice. Since 1838, the city’s central prison (named the Tombs because of its foreboding appearance and damp interior) was located just adjacent to Chinatown. The Fifth Police Precinct is also located at the center of this community at 19 Elizabeth Street. Although Chinatown was ranked 58th safest out of the city’s 69 patrol areas and has a crime rate well below the city average, the incarceration rate of 449 inmates per 100,000 people is slightly higher than the city average of 443 per 100,000. This incarceration rate is also significantly higher than adjacent neighborhoods like SoHo that have a rate well below 100 per 100,000. NYC Open Data reveals this neighborhood to be targeted for certain – perhaps race-specific and generally non-violent crimes – like gambling and forgery. Over half of all NYPD arrests related to gambling are in Manhattan Chinatown. Similarly, the only financial institution to face criminal charges after the 2008 financial crisis was Chinatown’s family-owned Abacus Federal Savings Bank – on allegations of mortgage fraud later found false in court by a 12-0 jury decision in favor of Abacus. Abacus provided mortgages and unconventional financial services to the kinds of immigrants traditionally locked out of the banking system, and therefore denied the means to climb the social ladder. The mistreatment of the Chinese in America both past and present is part of a larger anti-China agenda.

When it comes to tourism, Americans seem to have a paradoxical relationship with Chinatown’s “oriental” culture and cuisine. On the one hand, there is a proclaimed love of East Asian cuisine and art, as evidenced by the profusion of Asian-themed restaurants for tourists, or as evidenced by the phenomenon in art history for western artists (and particularly French Impressionists) to incorporate decorative motifs from East Asian woodcuts and ceramics into their work. On the other hand, there is simultaneously exclusion of the people who created this Chinese food and art from political power and social mobility. Still today, Americans seem to want competitively priced Chinese products without suffering the presence of the foreigners who produced these products.

Forsyth and Delancey Street

Let us clarify one thing: The division in Chinatown is not “apartheid” in the strict sense. It is perhaps a division more subtle and difficult to notice. It expresses the kind of unequal treatment – antiquated housing, crowded conditions, and municipal apathy – that face many immigrant groups in America. The built environment of Chinatown is something altogether more complicated and layered with other ethnic groups, too. For instance, the Church of the Transfiguration in the center of Chinatown now has a majority Asian congregation, even though it was founded in 1815 as a German and Lutheran church. Similarly, some of the funeral parlors on Mulberry Bend have Italian origins and old Italian men in the funeral bands. This neighborhood is also in the active process of gentrification with rising rents pushing out older Asian businesses.

If and when the Chinese become fully integrated into American society, how should the architectural fabric of this immigrant enclave be preserved, considering that its very existence is a marker of race-based exclusion and the century-long challenge of the Chinese in America?

.

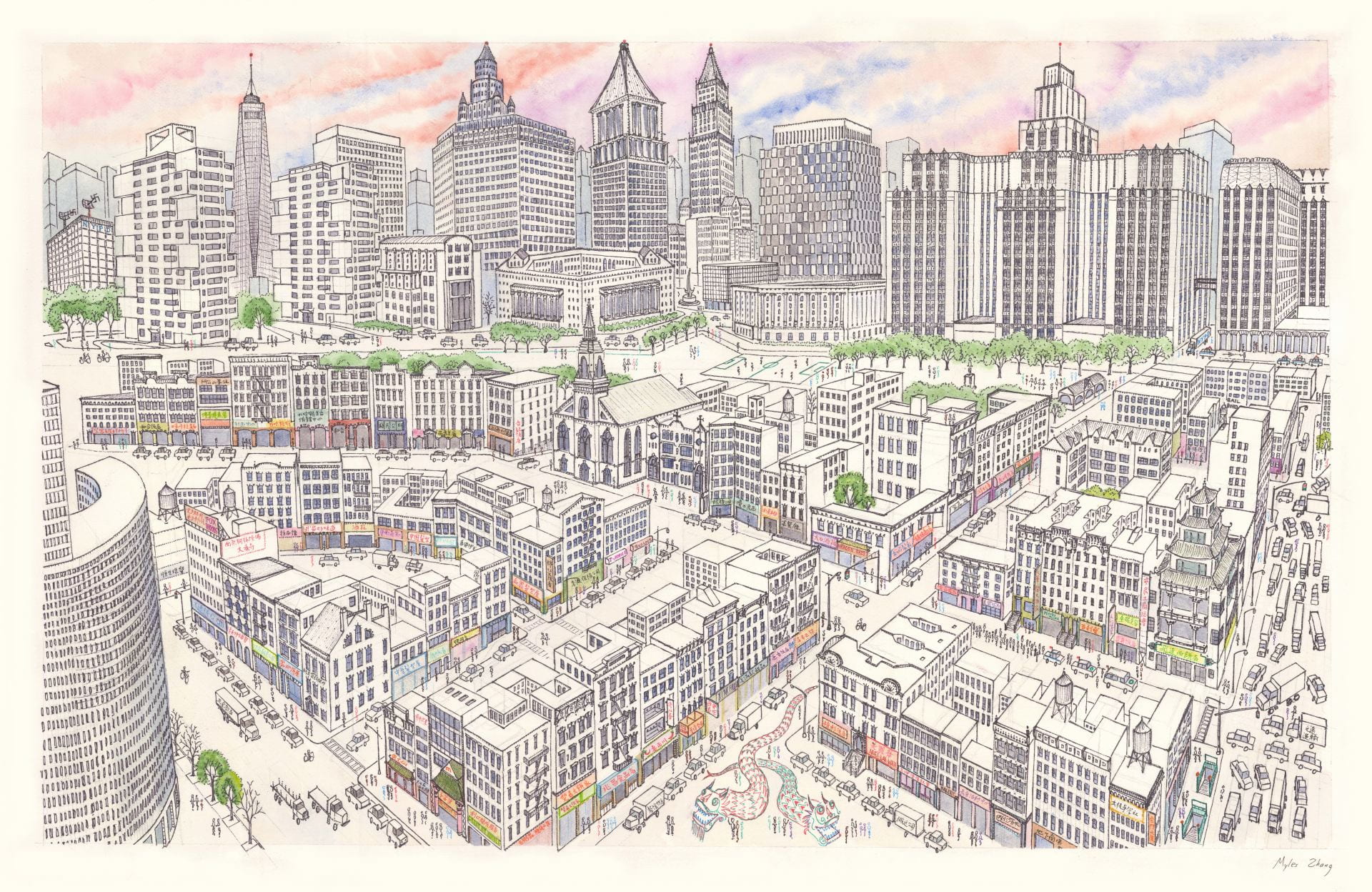

This time-lapse of Manhattan Chinatown took sixty hours to complete and measures 26 by 40 inches. Chinatown’s tenements are in the foreground, while the skyscraper canyons of Lower Manhattan rise on top. This shows the area of Chinatown bordered by Bowery, Canal Street, and Columbus Park.

.

Chinese music: Feng Yang (The Flower Drum)

The Panopticon and Trouble in Utopia

Ironically, the most unequal and dystopian of societies are often founded on utopian principles. Utopias, almost by their very nature, have undertones of conformism and oppression. From Plato’s Republic of strict castes and rampant censorship to Thomas More’s Utopia of puritanical laws and slavery, a utopia for the few is often a dystopia for the many. The question then arises: How do the benefactors of utopia confront its detractors? Utopia has several choices. It can maintain its monopoly on media and education, strangling nascent free thought before it grows into free action. Or it can physically punish and oppress free thought, which requires systems to detect and punish dissent. Detection requires gathering information about the populace. Punishment requires control and physical torture: the police, the army, and the prison. Ironically, to maintain power against its critics, utopia often adopts trappings of dystopia.[1]

Despite the seeming differences between them, many utopias and dystopias often resemble the panopticon, a model of the ideal surveillance state. In fact, panopticon, dystopic police state, and utopian society share common goals: total observation, total power, and unquestioned control.

.

The panopticon models the workings of a society.

The panopticon was initially an architectural concept for the ideal prison. Conceived in 1791 by Jeremy Bentham, an English-born philosopher, social reformer, and utopian thinker,[2] the panopticon embodies the ideals of observation, control, and discipline. In its physical form, the panopticon is a circular prison with cells ringed around a central tower from which prisoners can be watched at all times. This slender central tower contains a covered guardroom from which one guard simultaneously surveys hundreds of prisoners (see image below). The panopticon aims for constant surveillance and prisoner discomfort. In this all-seeing system, dissent is detected and discipline is enforced.

Read More

.

View computer simulation of panopticon.

The Old Essex County Jail

.

The old Essex Country Jail sits forlorn and abandoned amidst desolate parking lots and lifeless prefab boxes. In the so-called University Heights neighborhood, the jail is testimony to the past. Listed on the National Register of Historical Places, this 1837 structure is one of the oldest jails in America and the oldest civic structure in the city. Abandoned for over fifty years, no successful preservation efforts have materialized.

The urban jungle of junk trees, vines, and garbage conquers the old fortress. The warden’s garden that zealous prisoners once pruned and weeded is now overrun with nature. Used syringes line the cell-block floors. Not a single window is unbroken. Not a single wall is straight or strong. The rigid geometry that defined this urban castle is now blanketed in decay.

Yet, this fortress of old is still a home. A trail of homeless squeeze through the rusted barbed wire fencing. They carry with them their few odd valuables, cans to be recycled or shopping bags of discarded clothes. Every night, they sleep in the very cells their luckless brethren slept in decades before. Every day, they wander city streets in search of donations, food, and work. The physical prison of brute force and searchlights has evolved into the no less oppressive prison of poverty. Both prisons, new and old, are refuges for the luckless. As its occupants have changed, so has the prison. Both are ghosts. Both are vanishing.

.

Related content

-

Read my January 2021 article in The Newarker magazine.

-

Read this July 2020 article from Jersey Digs

about my exhibit and the New Jersey Institute of Technology’s proposal to reuse this jail site. -

Hear my September 2019 interview about this jail and exhibit from Pod & Market.

-

Explore this jail as an interactive exhibit online.

-

View this artwork as part of my short film from 2016 called Pictures of Newark.

.

.

.

Essex County Jail

Overgrown Courtyard

Essex County Jail

Decayed Stairs

Boiler Room

Essex County Jail

Children’s books left by homeless inhabitant and her family.

Mural