1913 to 2023

A century later, the mills of Paterson sitting abandoned, their machines silent

A century later, the mills of Paterson sitting abandoned, their machines silent

.

Audio testimonies from:

Pauline Newman letter from May 1951, 6036/008, International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Archives. Cornell University, Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives.

Louis Waldman eyewitness in Labor Lawyer, New York: E.P. Dutton, 1944, pp. 32-33.

Anna Gullo in the case of The People of the State of New York v. Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, December 11, 1911, pp. 362.

.

.

.

.

.

– Horse drawn carriage

– Power loom

– Workplace bell

– Classroom

– Large crowd

– Elevator

– Small fire

– Large fire

– Fire truck bell

– Fire hose

– Dull thud

– Heartbeat

– Closing song: Solidarity Forever by Pete Seeger, 1998

– Closing song: Solidarity Forever by Twin Cities Labor Chorus, 2009

.

1. Steven Manson, Jonathan Schroeder, David Van Riper, Tracy Kugler, and Steven Ruggles. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 17.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. 2022. http://doi.org/10.18128/D050.V17.0

2. Social Explorer. https://www.socialexplorer.com/

Click to launch interactive mapping experience.

.

.

.

From April 1898 issue of Scientific American

.

.

.

.

.

.

– Frédéric Rouvillois

Utopia: The Search for the Ideal Society in the Western World [1]

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Black children standing in front of half-mile concrete wall, Detroit, Michigan. This wall was built in August 1941, to separate the Black communities of Royal Oak Township / Eight Mile-Wyoming from a White housing development going up on the other side.

.

.

.

.

Lorch Column at Taubman College

.

.

.

Prudential Headquarters (across the street from Mutual Benefit, also demolished)

.

.

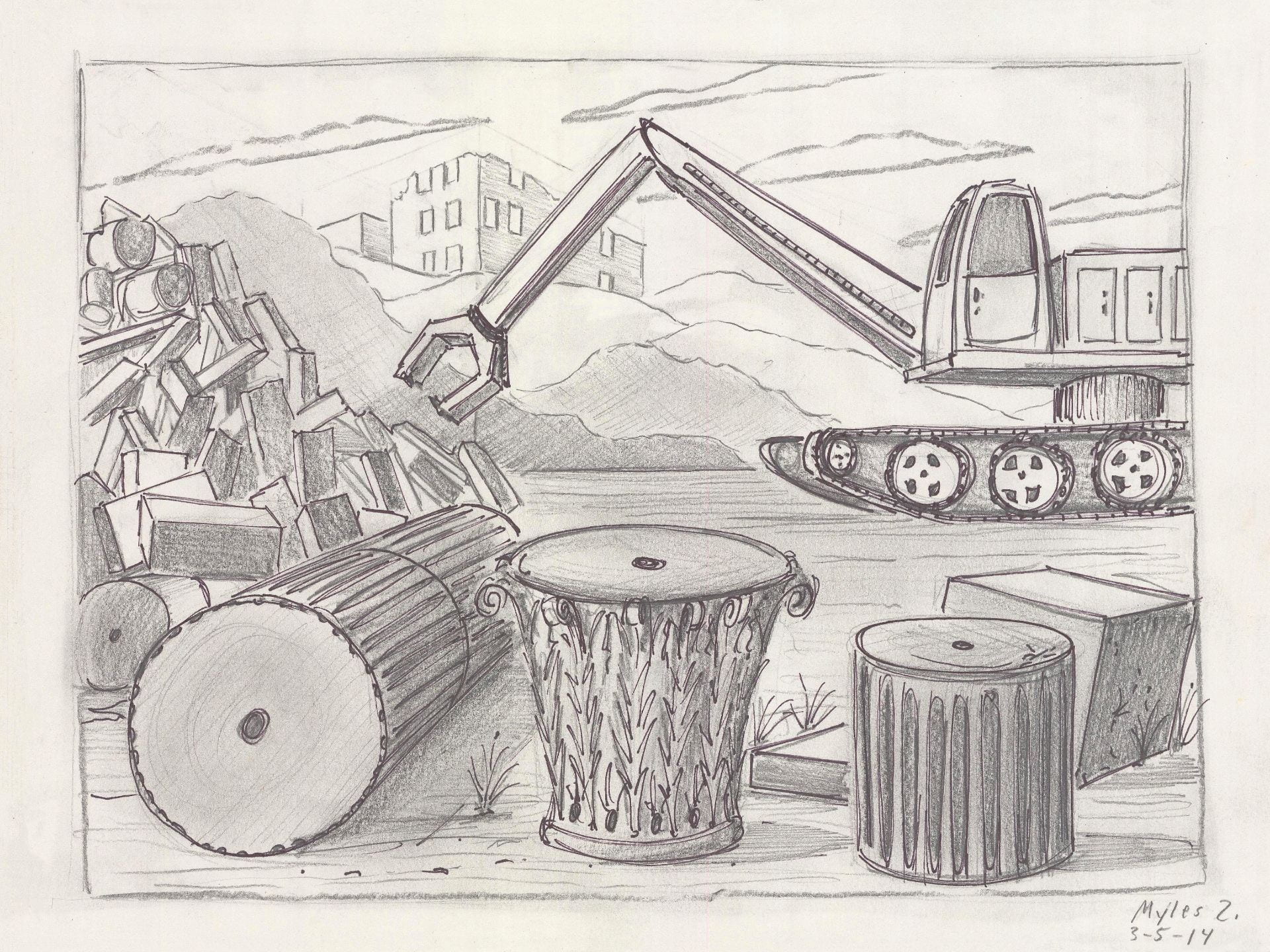

It’s not easy to knock down nine acres of travertine and granite, 84 Doric columns, a vaulted concourse of extravagant, weighty grandeur, classical splendor modeled after royal Roman baths, rich detail in solid stone, architectural quality in precious materials that set the stamp of excellence on a city. But it can be done. It can be done if the motivation is great enough, and it has been demonstrated that the profit motive in this instance was great enough.

.

.