Developed with Gergely Baics, urban historian at Barnard College

.

New York City has some of the world’s cleanest drinking water. It is one of only a few American cities (and among those cities the largest) to supply unfiltered drinking water to nine million people. This system collects water from around 2,000 square miles of forest and farms in Upstate New York, transports this water in up to 125 miles of buried aqueducts, and delivers one billion gallons per day, enough to fill a cube ~300 feet to a side, or the volume of the Empire State Building. This is one of America’s largest and most ambitious infrastructure projects. It remains, however, invisible and taken for granted. When they drink a glass of water or wash their hands, few New Yorkers remind themselves of this marvel in civil engineering they benefit from.

This animated map illustrates the visual history of this important American infrastructure.

.

Sound of water and ambient music from Freesound

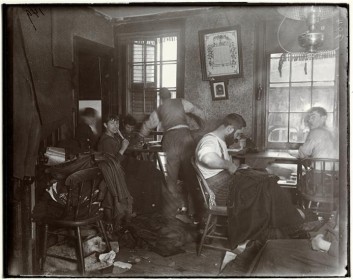

New York City is surrounded by saltwater and has few sources of natural freshwater. From the early days, settlers dug wells and used local streams. As the population grew, these sources became polluted. Water shortages allowed disease and fire to threaten the city’s future. In response, city leaders looked north, to the undeveloped forests and rivers of Upstate New York. This began the 200-year-long search for clean water for the growing city.

.

Credits

Gergely Baics – advice on GIS skills and animating water history

Kenneth T. Jackson – infrastructure history

Juan F. Martinez and Wright Kennedy – data

.

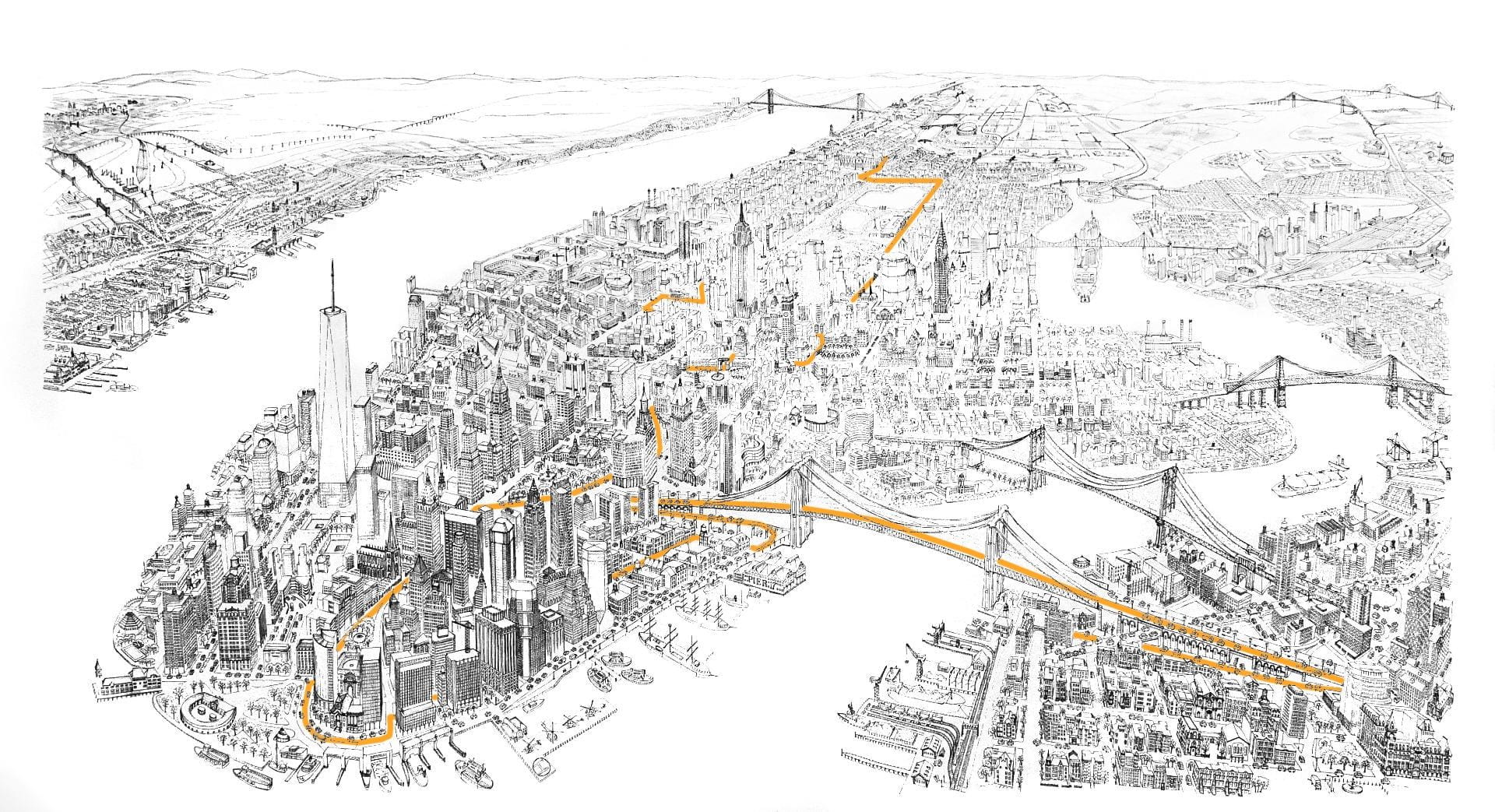

Interactive Map

I created this animation with information from New York City Open Data about the construction and location of water supply infrastructure. Aqueduct routes are traced from public satellite imagery and old maps in NYPL map archives. Thanks is also due to Juan F. Martinez, who created this visualization.

Explore water features in the interactive map below. Click color-coded features to reveal detail.

.

Watersheds Subsurface Aqueducts Surface Aqueducts Water Distribution Tunnels City Limits

.

▼ For map legend, press arrow key below.

.

Sources

.

For such an important and public infrastructure, the data about this water supply, aqueduct routes, and pumping stations is kept secret in a post 9/11 world. However, the data presented here is extracted from publicly-available sources online, and through analysis of visible infrastructure features on satellite imagery when actual vector file data or raster maps are unavailable from NYC government.

.

Contemporary Maps

.

.

Encyclopedia of the City of New York – Kenneth T. Jackson

.

Audio narration – Myles Zhang

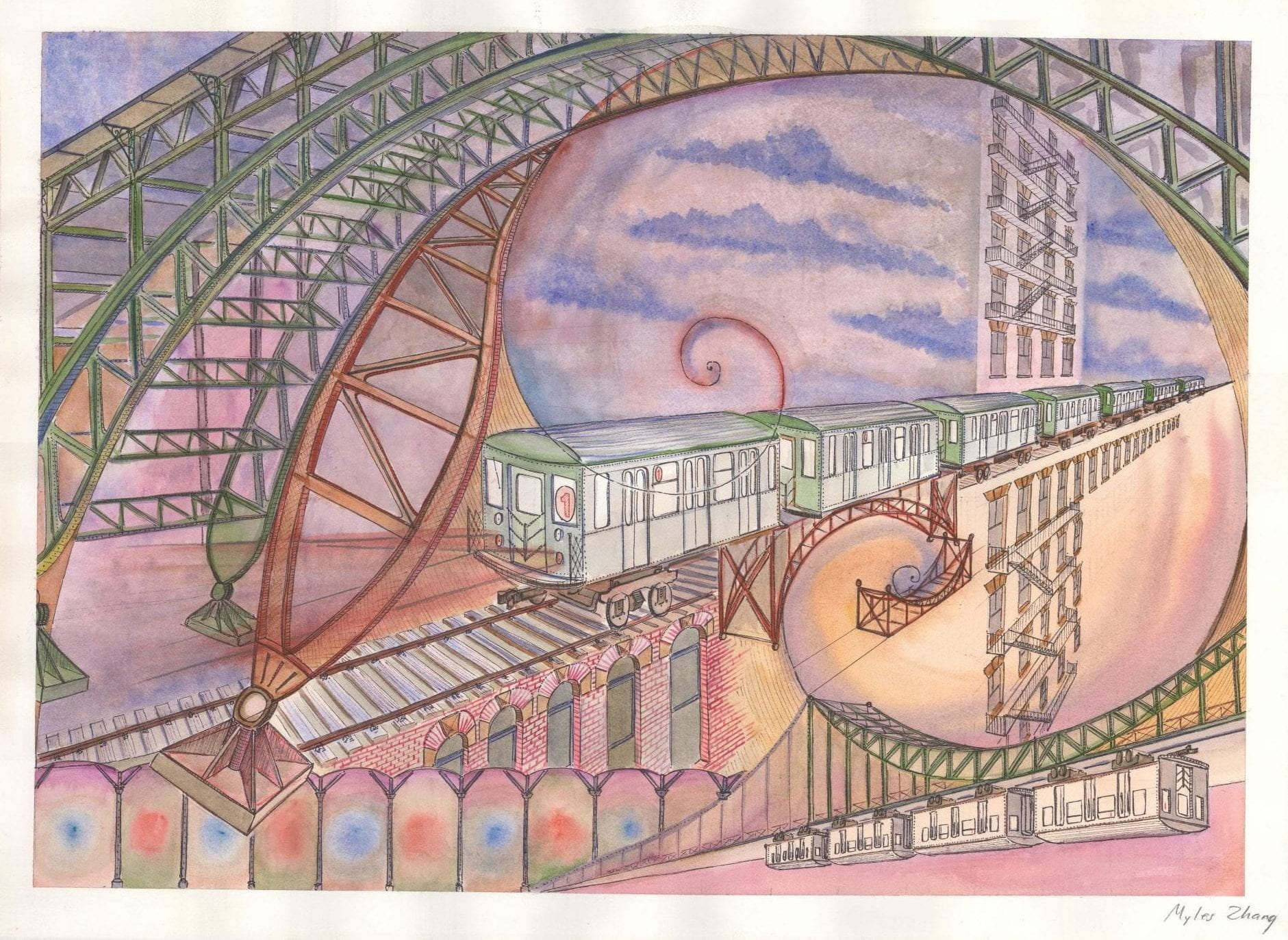

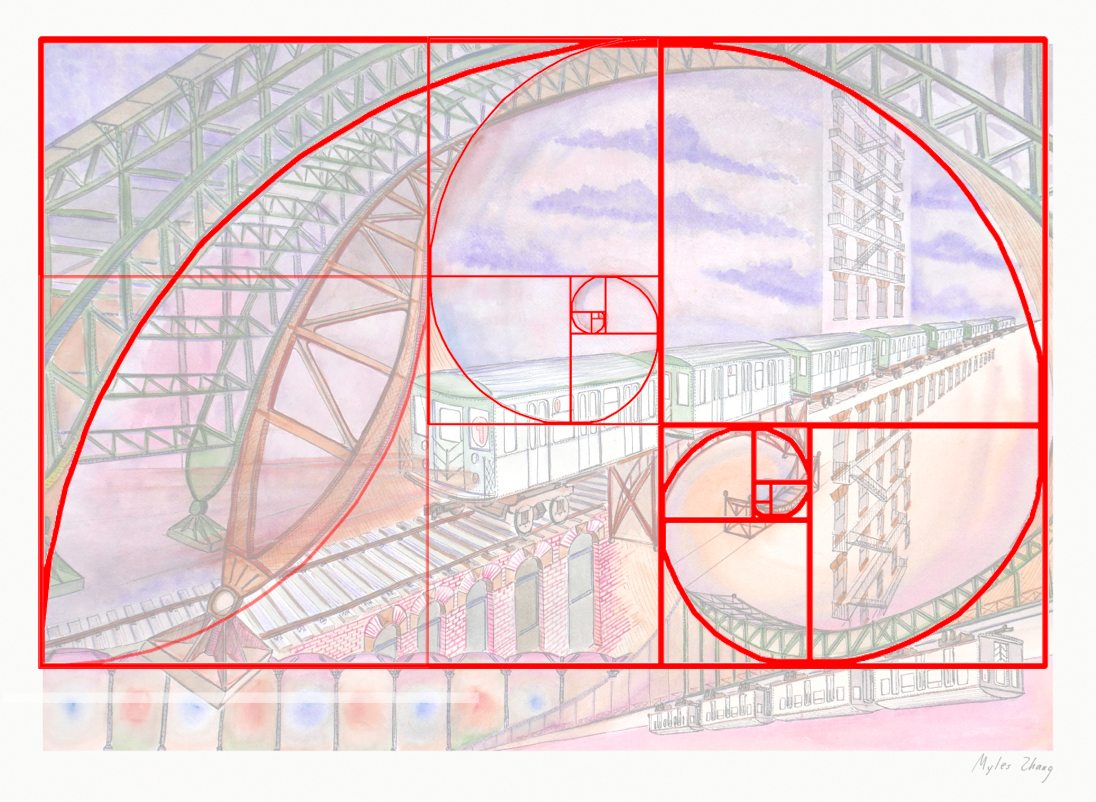

As northbound Broadway dips down to the valley of 125th Street, the subway soars over the street. The subway viaduct is a jumble of steel slicing through the orthogonal city grid. The 125th Street viaduct is a massive arch, 250 feet from end to end, two hundred tons of mass channeled into four concrete pylons, resting on the solid bedrock of Manhattan schist. The subway is the intersection, where the underground and aboveground worlds of New York City converge.

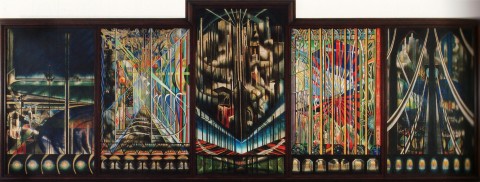

As northbound Broadway dips down to the valley of 125th Street, the subway soars over the street. The subway viaduct is a jumble of steel slicing through the orthogonal city grid. The 125th Street viaduct is a massive arch, 250 feet from end to end, two hundred tons of mass channeled into four concrete pylons, resting on the solid bedrock of Manhattan schist. The subway is the intersection, where the underground and aboveground worlds of New York City converge.