.

The best definition of a university is, to my mind, a city from which the universe can be surveyed. It is the universe compressed into a city the size of Morningside Heights.

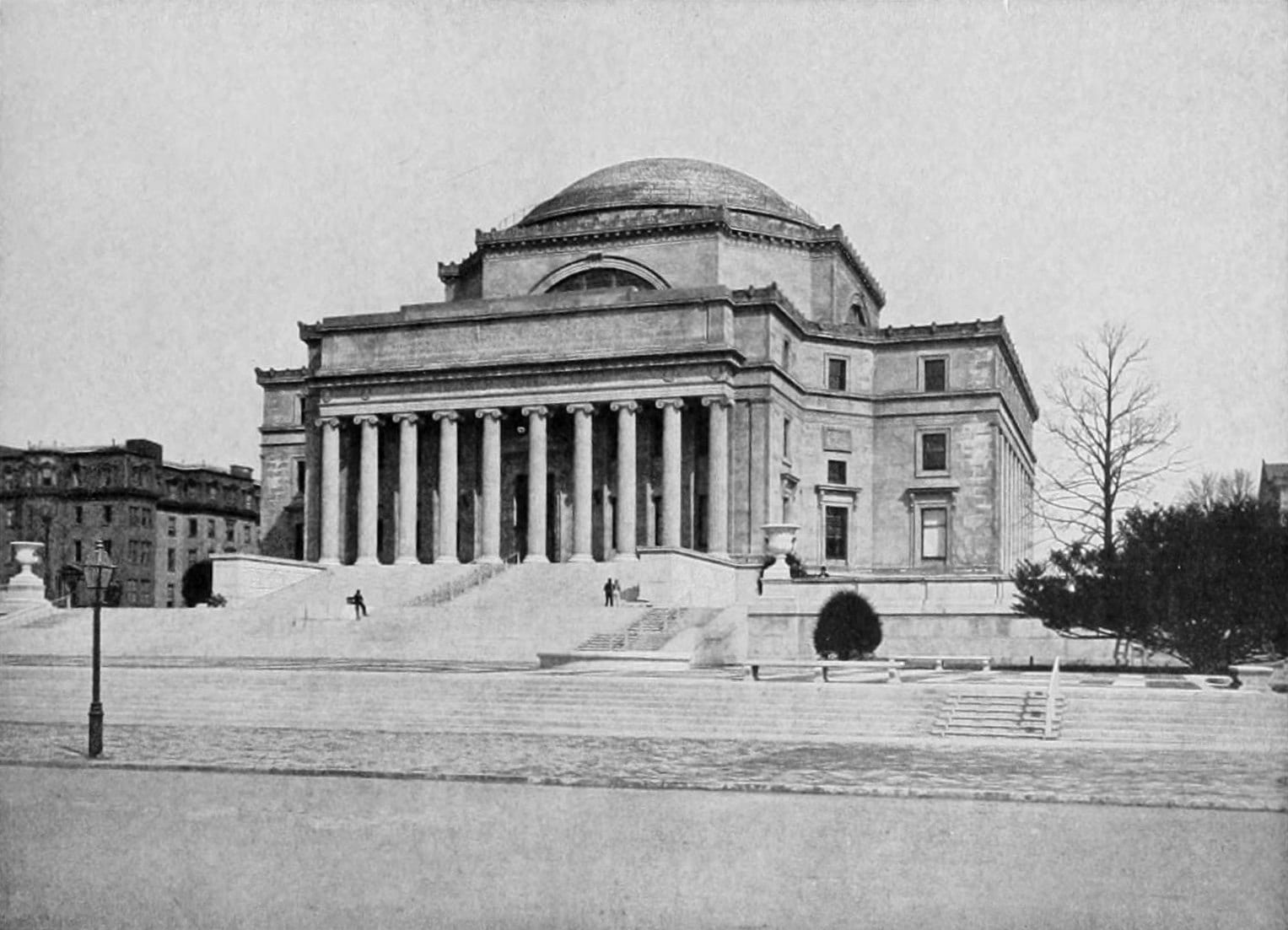

Aesthetically ancient but technologically advanced, Low Library rose to this challenge in the 1890s. Buried within hundreds of tons of Milford granite, Indiana limestone, and the unchanging architecture of antiquity were the latest technologies: electricity, steam heating, Corliss steam engines, and internal plumbing in a time when hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers still used outhouses and made less than five dollars a day. Flushing toilets – also known as crappers after Thomas Crapper who perfected their flush mechanism – were also a relatively new consumer product. It has always surprised me how the bathroom stalls at Low Library are divided by marble partitions of the highest quality that must weigh several hundred pounds each. Low Library was indeed built at a time when toilets were something to celebrate, in addition to books of course.

The goal of a great library was to collapse the universe into the size of a room. From the dome’s center was suspended a seven-foot-diameter white ball, which Scientific American described in 1898 as “Columbia’s artificial moon.” So that students could read by moonlight under a canopy of stars, this moon was illuminated against a dome painted dark to resemble the night sky. So in awe was Scientific American that they devoted as much page space to describing Low Library as to documenting the mechanics of this moon with mathematical formulas. With no other point of reference except candles, scientists calculated Columbia’s moon as equivalent in power to 3,972 candles.

.

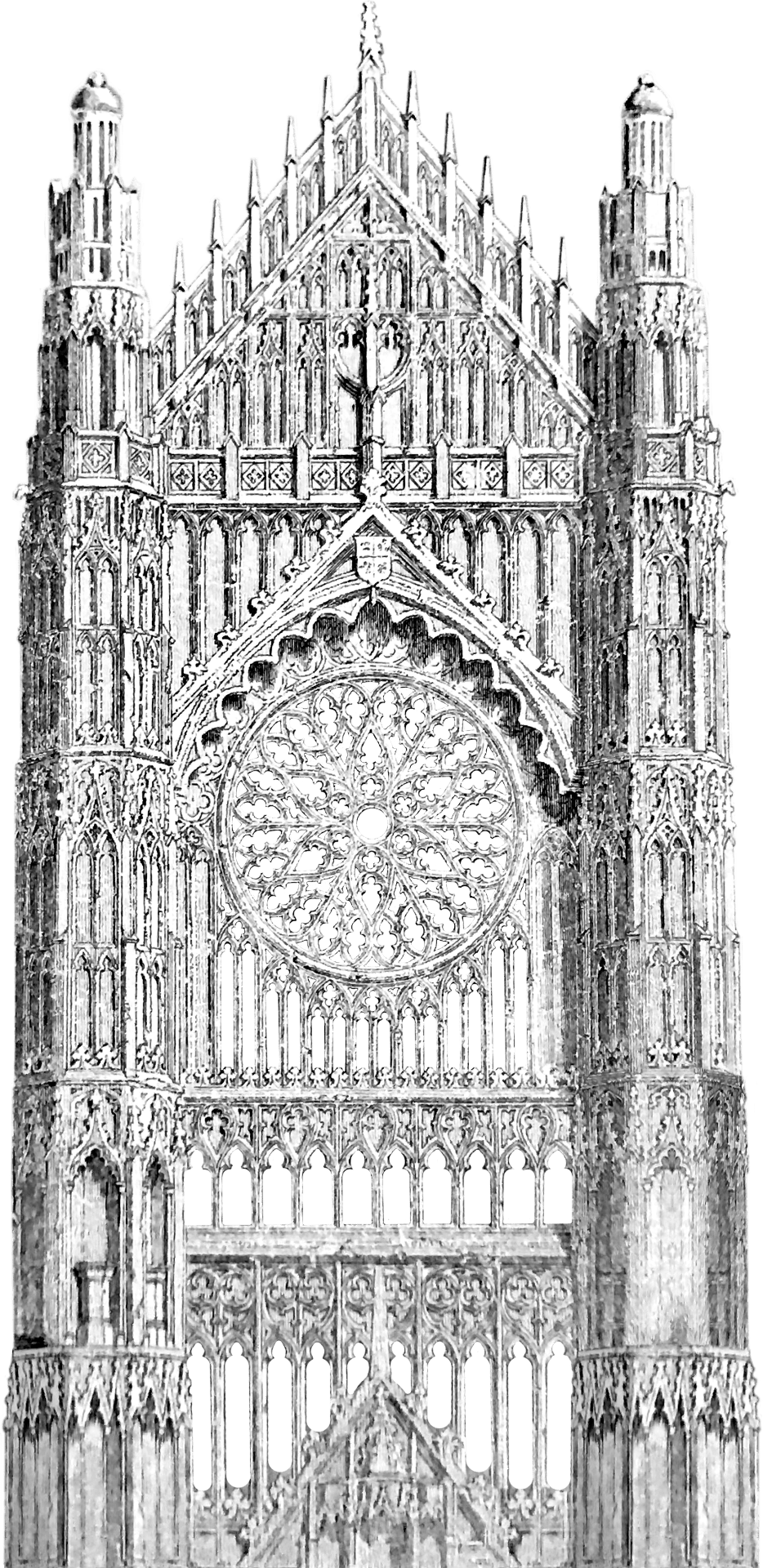

From April 1898 issue of Scientific American

.