The work stoppage at Halo tower construction site points to why we need a different model of economic development.

As also published by the local paper TAPinto

.

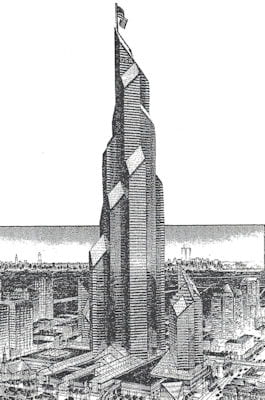

Jersey Digs and TAPinto reported last week that amid lawsuits and protests, work had stopped on the 38-floor Halo skyscraper in Newark. The developers claimed that their lender was unable to make good on the $90 million construction loan. If the developer is unable to get their funds in order, that tower will become another rusting and unfinished shell like Harry Grant’s proposal to build the world’s tallest skyscraper in Newark. Until it was demolished to build Prudential Center, Grant’s unfinished Renaissance Mall abandoned mid-construction was a visual eyesore on Broad Street for decades.

At 38 floors with 297 units, the per unit cost of construction of Halo will be just over $300,000. This is one of the more expensive towers downtown. By comparison with another recently completed project, at 21 floors with 264 units, the per unit construction cost was $240,000 at Walker House. (source) Halo tower is all new construction. Walker House is adaptive reuse of an existing historic building. Based on industry data, adaptive reuse of old buildings costs 16 percent less than ground-up construction, and it reduces construction schedules by 18 percent. (source)

For many new projects, the cost of using all new materials, steel structural frames, and concrete floors will increase the cost of construction. Instead of building from scratch like at Halo, downtown Newark still has no shortage of vacant and century-old office skyscrapers that could have been converted to residential use. Newark has no shortage of vacancies: the 16-story Firemen’s Insurance Company Building, the 12-story Kinney Building, the 10-story Chamber of Commerce Building, the 20-story IDT building, the 15-story Griffith Building, as well as dozens of other smaller-scale vacant buildings near Broad and Market. The adaptive reuse of these older structures is also eligible for significant Historic Preservation Tax Credits that can cover up to 20 percent of all construction costs. This is a more sustainable business model.

In addition, the Downtown Newark BID reported that in 2023, about one sixth of all downtown office space was vacant (source). This figure does not include the above vacant office towers that have been off the market for decades and are not currently available to rent. At the intersection of Broad and Market, the ground floors of most buildings are occupied. But the upper floors are entirely vacant – many for decades. Factoring in all buildings in downtown Newark, the actual vacancy rate is a good deal higher and approaches thirty percent by my estimate.

To insist on all new construction when the vacancy rate is so high in older existing structures does not make good economic sense. The priority should be to solve the existing vacancy rate before embarking on ambitious new construction, particularly in our city’s historic districts.

Despite tax breaks and state subsidies for downtown Newark that total more than a billion dollars in the past thirty years (source), the downtown property market remains fragile. My concern is that putting up many new luxury towers in a time of soft market demand will not address either the vacancy problem or the need for long-term and permanent affordable housing.

Beyond high-rise skyscrapers, there is another (and more sustainable) development model we should be encouraging: the incremental construction of mid-rise infill buildings in existing neighborhoods. Instead of a skyscraper like Halo perched on a five-story car garage at street level, downtown developers need to focus on filling in the gaps in our urban fabric. Downtown Newark has at least 200 acres of surface parking. (source) The priority should be filling this land to create complete streetscapes and an uninterrupted row of occupied buildings on a walkable sidewalk.

The developers and lawyer behind Halo and copy-cat projects of near-identical design at 577 Broad Street say that we have a housing shortage, and building more luxury towers will solve that shortage. The historical record does not support this claim. Manhattan had a population 40 percent larger in the 1910s, and Newark had a population 40 percent larger in the 1950s. Both cities accomplished this feat of downtown population density entirely through mid-rise construction during a time before skyscrapers. The results were neighborhoods of small buildings, instead of a complex of super tall buildings – isolated from the street and cut off from the city like Newark Gateway Center. Today, as in history, the past provides examples of successful and unsuccessful urbanism. Let us learn from history.

.