What kinds of tax breaks are we giving to redevelop Downtown Newark?

Who is getting them?

An investigative report on public funds for private profit.

.

“Free enterprise is a term that refers, in practice, to a system of public subsidy and private profit, with massive government intervention in the economy to maintain a welfare state for the rich.”

– Noam Chomsky

.

Contents

[1] Who owns the land around Mulberry Commons?

[2] If past predicts future, what kind of past tax breaks have we given?

[3] The problem is not tax breaks. The problem is: Who gets them?

[4] How can we ensure equitable economic development in Newark?

Five policy recommendations.

.

Artist’s rendering of Newark Penn Station expansion

.

Introduction: A Case Study in Edison Parking

The City of Newark borrowed $110 million to pay for a pedestrian bridge over Route 21. This new link between Mulberry Commons and Penn Station will allow travelers, event goers, and sports fans to walk directly from the trains to the games at the arena. Newark City Hall and the media are describing this as Newark’s equivalent and response to New York City’s High Line. This project follows on the already $10 million spent on building Mulberry Commons.

As part of misguided car-centered 20th-century urban planning, thousands of highways were built in our nation through low-income communities of color, to divide the less privileged in hundreds of places like Newark. Through the tools of public investment in public space, now is a moment to make wrong historical injustices like Route 21, Route 22, Interstate 78, and Interstate 280. Now is a historic opportunity for the urban form as tool of reparations.

However, what parts of the public – divided across lines of race, income, and home address – will benefit the most from this project? Will the benefits of this investment disproportionately go to a few people or institutions, such as Prudential Center patrons and Edison Parking tenants?

Read More

.

[1] Who owns the land around Mulberry Commons?

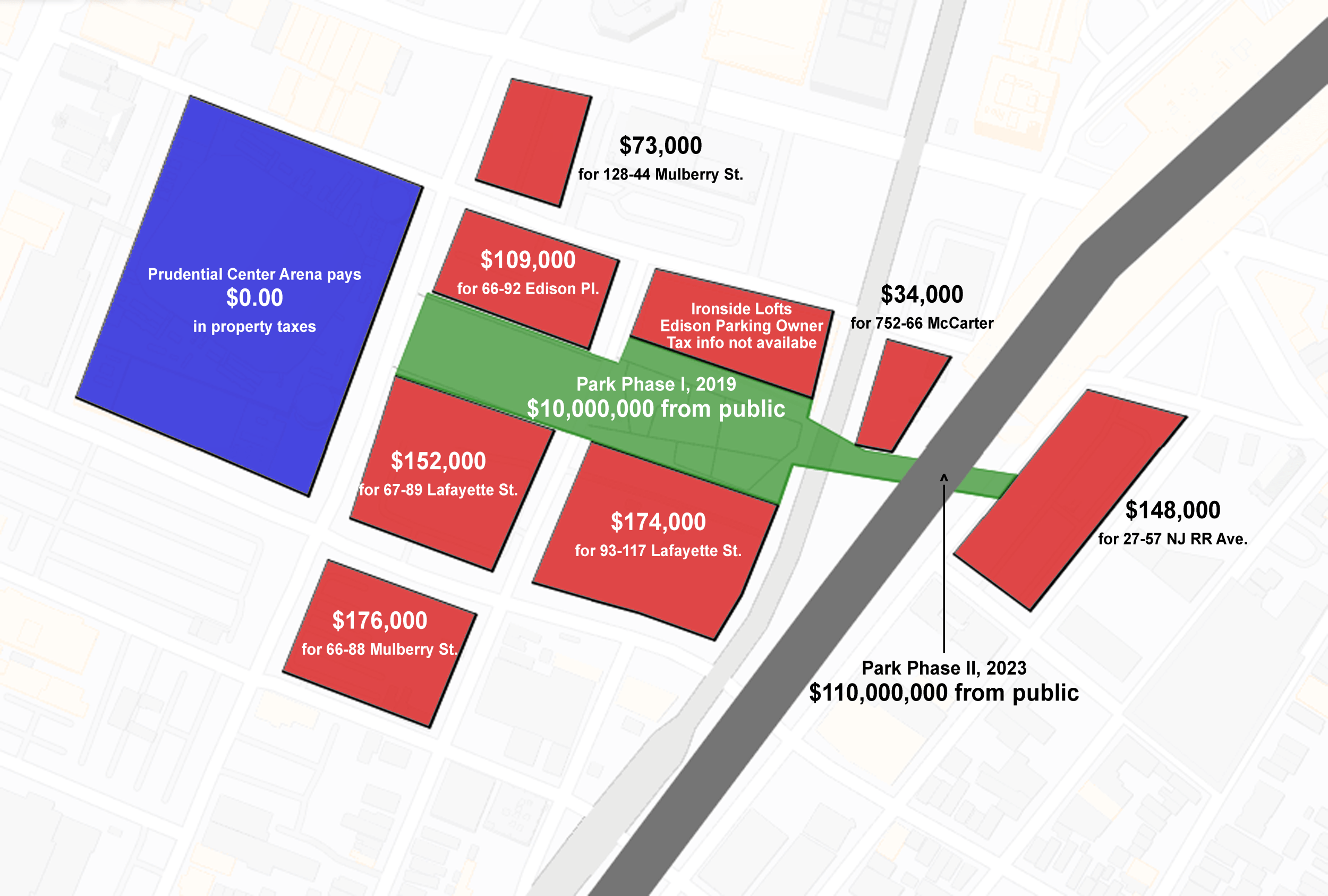

This map shows the location of the expanded Mulberry Commons in green. One company, Edison Parking, owns property on every side of this public space, except for the arena. The map notes Edison Parking’s land and the amount they pay in property taxes. Public records indicate the arena is on Newark Housing Authority land. The city assessed that property as worth $252 million and charges no property taxes.

In return for this $120 million investment, Edison Parking pays the city just $870,000 in property taxes, plus a variable amount each year in parking lot usage fees (source from public records). The interest payments on Mulberry Commons are at least four million per year. That is, it is likely the city spends more on services that benefit Edison Parking than Edison Parking pays the city in property taxes. It is time for the city to reassess the taxes of multinational corporations based in Newark, so that they pay their fair share.

Will Edison match this investment of public funds with improvements to their property? More importantly, who will pay Edison Parking to improve their property? What kinds of tax breaks or tax incentives for transit-oriented development will Edison receive to develop these valuable 11 acres of land?

For comparison, when public funds paid for the High Line in New York City, Edison Parking owned just two acres next to the High Line. They sold those two acres for $800 million in 2014 in one of the most expensive land deals in New York City history. In 2021, Edison beat its own record and sold off the assets it managed under the affiliate brand name Manhattan Mini Storage. The sale price was three billion dollars. How Edison distributed this three billion in sales is unclear because the company is not publicly traded on the stock market and therefore does not release regular annual reports. But this kind of money does give them a powerful war chest to spend in Newark: on campaign contributions, on lobbying politicians, and paying lawyers to reduce their tax liability.

If history is a lesson, that story of Edison Parking’s High Line in New York City will repeat itself with Mulberry Commons in Newark.

.

[2] If past predicts future, what kind of past tax breaks have we given?

The past is often the best prediction for the future. Here is how much several other new developments in Downtown Newark received in public funds and tax breaks:

Project

|

Public Funds |

Year |

| Prudential Sports Arena | $200 million | 2004 (source) |

| Prudential New Headquarters | $210 million | 2012 (source) |

| Panasonic New Headquarters | $102 million | 2013 (source) |

| Hahne’s Building | $129 million | 2016 (source) |

| Mars Wrigley in Edison Parking’s Building | $31.5 million | 2018 (source) |

| Shaquille O’Neal Tower on Rector Street | $29 million | 2019 (source) |

| Hello Fresh | $37 million | 2020 (source) |

| Fabuwood Cabinetry Corporation | $39 million | 2020 (source) |

| Audible | $39 million | 2020 (source) |

| Wakerfern Food Corporation | $27 million | 2020 (source) |

| The Portnow at Newark Broad Street | $90 million | 2023 (source) |

And billions of dollars more…

The interactive graphic below visualizes an estimated 1.8 billion in tax breaks that the New Jersey Economic Development Agency handed out since 2007. Hover over individual dots to display the amount given for each project, and the percentage of project costs paid for with public funds. These are rarely direct and one-time cash payments from the state to the developer. Instead, they are tax breaks that reduce the developer’s tax bill over a period on average ten to twenty years.

For instance, Prudential received at least $210 in public funds to move their headquarters from Newark’s Gateway Center to Military Park. The move brought few permanent new jobs to Newark. The project instead shuffled office workers from an older building that Prudential rented to the current building Prudential owns tax free and rent free. Similarly, Amazon was promised upwards of seven billion dollars in tax breaks and public incentives to encourage them to move their second global headquarters to Newark. Mulberry Commons was advertised to Amazon as the prime real estate for them to build in Newark, with Edison again first in line to benefit from new construction.

.

This infographic is an estimate, not a statement of precise fact. The data is obtained from the New Jersey Economic Development Agency through my Open Public Records Act request. The data is unclear if certain payments to developers are one-time or recurring. So some figures above may be double counted because of lack of clarity in the New Jersey Economic Development Agency reports that are made public.

Based on historical trends, and the $120 million investment in a public park surrounded by Edison Parking’s land on all sides, we can assume Edison will receive multi-million (billion?) dollar tax breaks and tax credits to develop this land. The financing structure that allowed the companies in the above graph to obtain more than a billion dollars in tax write offs have not changed fundamentally changed since the program began. So, in addition to the $120 million in public funds already spent on Mulberry Commons, Edison will be eligible for and will receive further tax breaks. The proximity to Penn Station makes Edison Parking eligible for the Urban Transit Hub Tax Credit Program that gave Panasonic about $80 million.

The main justification for tax breaks is that: “If we do not offer them, then development will not happen.” This is argument is sometimes true, sometimes false. Thirty years ago, this argument was justified: Developers and outsiders were scared of Newark and needed to be rewarded with tax breaks to build here. In 2023, this argument holds less weight: Newark is already so attractive to development and investors that it is likely these developments would have happened anyway without tax breaks that total billions of dollars over the decades.

.

[3] The problem is not tax breaks. The problem is: Who gets them?

Tax breaks are an essential tool. Small developers and small business owners need them: for projects between 10 and 100 units. They have less in savings, and limited access to banks for loans. Historic buildings with expensive adaptive reuse need tax credits, too. The Hahne’s Building probably would not have been developed without tax credits, and nor would many other historic buildings that enrich the quality of our city’s neighborhoods. But tax breaks for Edison Parking, Panasonic (26 billion net worth in 2023), Prudential (35 billion valuation), Amazon (1.3 trillion valuation)? These companies own land worth billions of dollars, prime real estate in the world’s most expensive corners. Amazon pays little in taxes. The world’s wealthiest man Jeff Bezos paid no income taxes in 2007 and 2011. Why are we offering these companies more incentives to build in Newark?

Large corporations receive benefits not offered to smaller entities. Homeowners who renovate their properties do not receive tax breaks. Small developers creating infill housing, for example a 10-unit apartment building for middle income rent, do not receive tax breaks. Business owners who make improvements to storefront properties do not receive tax breaks. Only large properties apply for and receive tax incentives for adaptive reuse of historic buildings. Small owners of historic property do not receive these tax breaks. Big developers receive credits for building dozens of units of affordable housing. Small investors building or owning just a few units receive no such benefit.

Tax breaks for the very wealthy increase the cost of business for everyone else. When big players in Newark use public funds to pay for – in effect – 50 percent or more construction costs, then small players have trouble to compete. This approach inherently fosters monopolistic tendencies and undermines the core principles of fair play. It essentially amounts to corporate welfare disguised as a public benefit, with keywords like diversity and inclusion used to disguise the underlying lack of genuine diversity and deep exclusion perpetuated by these tax breaks. Incentives primarily serve to solidify the positions of larger players, further exacerbating the inequality that has plagued our city for decades and preventing new, more diverse players to emerge. To mitigate this imbalance, we must consider either extending these incentives to a wider range of entities or eliminating them altogether.

Tax breaks must be used as tool to even the playing field, not make it more uneven.

.

[4] How can we ensure equitable economic development in Downtown Newark? Six recommendations.

This project is a stub, an expensive skywalk from Penn Station to Mulberry Commons, a project whose form recalls some of the most egregious strategies of urban planning whereby skywalks were built all over major cities to segregate white collar workers from city sidewalks. We have plenty of examples in close proximity to the proposed Mulberry Commons bridge, and their detrimental effect on the streetscape in downtown Newark is evident. The new bridge will not meaningfully connect with Ironbound. On the east side, a narrow staircase descends some 50 feet elevation from Penn Station to parking lots, again owned by Edison Parking.

1. Expand the quality of public space: A further investment should continue this “High Line” Park on a gentle slope down to street level in the Ironbound. Ironbound residents would then be able to walk from their neighborhood to Downtown Newark on a path without cars, crosswalks, or stairs of any kind. This will require the park to cut through Edison Parking’s lot in the Ironbound, and for Edison Parking to commit more of its land to public benefit. Otherwise, Edison Parking can erect a skyscraper at this location, blocking easy access between the Ironbound and this park.

2. Public accountability through public meetings: The park stops at Edison Parking’s property line. They could build towers here, cut off from the rest of the city as pockets of luxury in a city of poverty. Or they could build affordable housing here, accessible to all in an open neighborhood. They could build another Gateway Center here: isolated from the city and turned inward with skywalks that allow people to work there without ever setting foot in Newark. Or they could build a new neighborhood here that is linked from all sides into the street network of other neighborhoods. Everything depends on our power, as the public, to ensure public accountability in city planning.

3. Set aggressive benchmarks that corporate recipients of state aid must meet. And if they do not meet them, they should be required to repay. In Mulberry Commons, public funds to build the park should have been match with signed legal “memorandums of understanding” with Edison Parking, promising to develop within X number of years.

4. Make accurate tax assessments based on land value, instead of property value: We need an accurate re-assessment of Edison Parking’s land values. These valuable acres must be reassessed at fair property tax value now that this massive infrastructure investment gives them direct connection to mass transit. Edison Parking should also be required to sign legal agreements promising to develop these lands within a set number of years, or risk penalties. The city could also revise its tax system to charge higher rates on vacant land than on developed land. By increasing the carrying costs of owning vacant land, land bankers have more trouble holding their empty land and therefore more incentive to develop it.

5. Move from a carrot model of economic development (tax credits) to a stick model of economic development (tax fines): We must evaluate the necessity of tax incentives for undeveloped lots in Downtown Newark. The current model pays land owners to develop: a carrot. A future model could fine landowners when they do not develop: a stick. In times of economic crisis when financing is difficult, we should consider tax incentives to developers to stimulate construction. In times of economic growth when financing is easy, we should consider tax penalties for land owners who choose not to develop.

6. Move tax incentives to prioritize new development that is not in downtown. Since the landowner is receiving a valuable public amenity in Mulberry Commons and Penn Station, further tax incentives are no longer warranted. Incentives for developing these lots are already apparent, thanks to their proximity to multi-modal transit and a sizable public park right at their doorstep. With or without tax incentives, corporations have reasons to build in Downtown Newark.

Can we agree that these existing incentives are sufficient to encourage development? Can we agree that further incentives are unnecessary? Can we also agree that any future tax incentives should be redirected towards areas of the city in greater need of development, where investors genuinely require persuasion? Can we also agree that future infrastructure improvements, like public parks with greenways and skywalks, should likewise be redirected to the criminally underdeveloped areas of the city?

.

7. This list is not complete.

The public has invested millions in Edison Parking and dozens of other downtown players. Now is the time for Edison Parking and corporations like it to give back to the city.

.

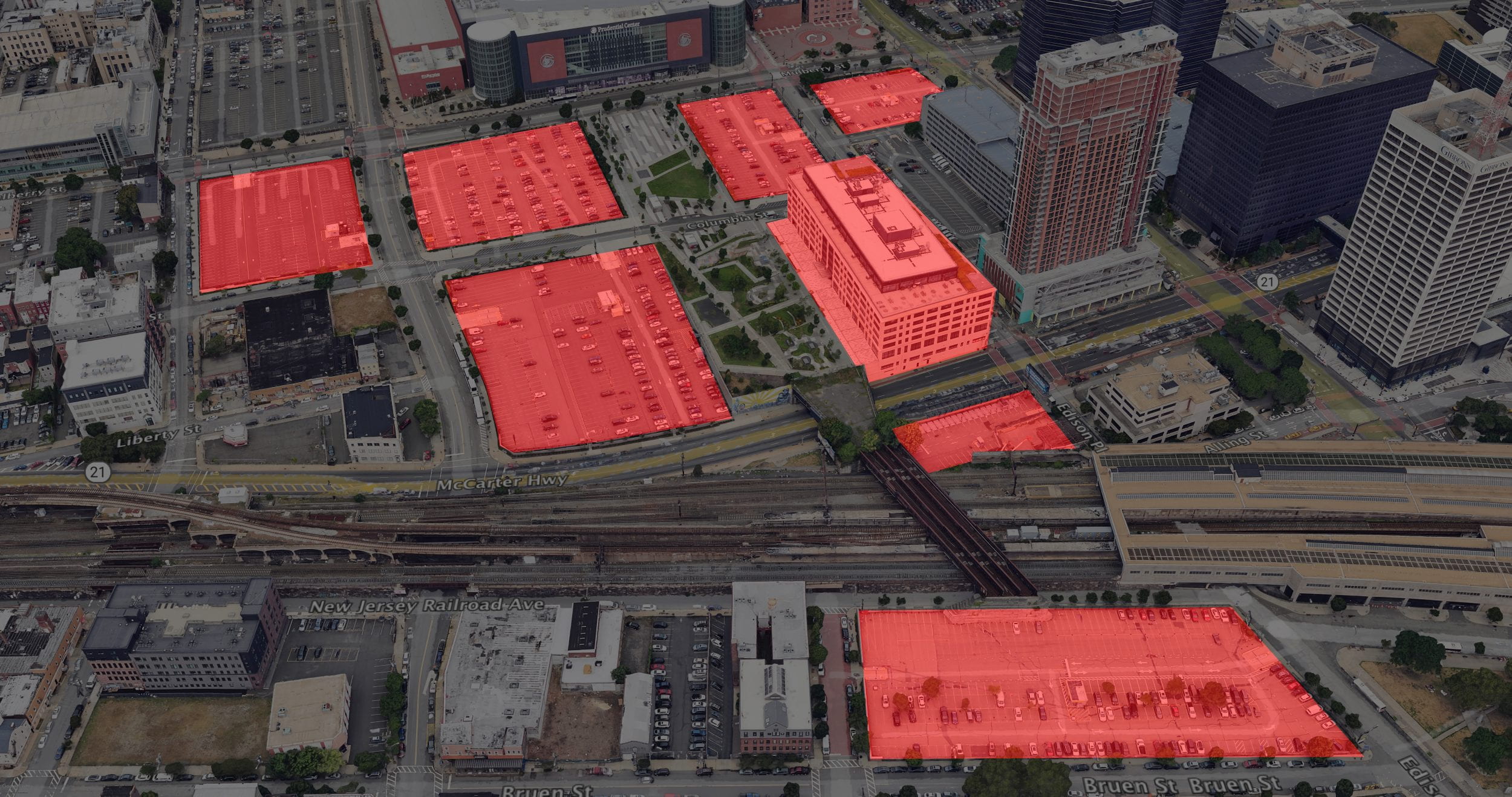

Everything beneath the sun… Edison Parking’s land highlighted in red

On the surface it appears that our political leaders do not have faith in Newark. Some people suspect that there may be more sinister motives behind the scenes.